For a long time, I’ve thought that economic thought took a turn for the worse beginning around 1870, with Karl Menger and Alfred Marshall. Before then, economics was a subset of politics and government, with “politics” here not to mean winning elections so you can steal a lot of money, but with its historical meaning of:

1a : the art or science of government.

Today, we usually use the word “government” for this purpose. The study of “political economy” thus meant: the study of government economic policy, as opposed, for example, to “household economy,” which is where the word “economics” originally comes. This was, like other studies of politics and government, a somewhat broad, literary, and philosophical topic, which had been discussed since ancient times.

Read Politics, by Aristotle, circa 350 B.C. Confucius (sixth century B.C.) and Mencius (third century B.C.) also discussed “political economy” (government economic policy) in great detail. Mencius was a tireless advocate of the “well-field system” of taxes, which was an effective 11% tax rate (very low at the time) on farmers.

This is the discussion of “political economy” that has come down through the millennium.

Before the 1870s, the defining work of “political economy” was Principles of Political Economy, by John Stuart Mill. Mill, and others of his day and earlier such as Ricardo and Smith, took a wide-ranging, if often episodic and disorganized, view of economic topics. Prices, interest and money of course engaged their interest, but so did taxes (read On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo), regulation of all kinds, warfare, plague, famine, legal foundations, welfare programs, and any other practical matter of statecraft.

However, after 1870 or so, economics gained a sense of physics-envy. Economists wanted to make their study more scientific. Math makes a big appearance. This tended to exclude all those aspects of public policy that are hard to quantify — try to quantify the economic advantage of the introduction of the LLC structure, as opposed to the prior S-Corp, for example — and to reduce the focus to prices, interest, and money.

The focus of the time, and which has continued largely unchanged to the present, was on “equilibrium theories” vaguely inspired by ideal gas laws and other discoveries of physics. Leon Walras is known today for his “general equilibrium theory,”described in his 1874 book Elements of Pure Economics. (“Pure” economics? Without the messy unquantifiable bits?)

Separately but almost simultaneously with William Stanley Jevons and Carl Menger, French economist Leon Walras developed the idea of marginal utility and is thus considered one of the founders of the “marginal revolution.” But Walras’s biggest contribution was in what is now called general equilibrium theory. Before Walras, economists had made little attempt to show how a whole economy with many goods fits together and reaches an equilibrium. Walras’s goal was to do this. He did not succeed, but he took some major first steps. First, he built a system of simultaneous equations to describe his hypothetical economy, a tremendous task, and then showed that because the number of equations equaled the number of unknowns, the system could be solved to give the equilibrium prices and quantities of commodities. The demonstration that price and quantity were uniquely determined for each commodity is considered one of Walras’s greatest contributions to economic science.

Their conclusions were something like this:

Prices: Prices change so that supply meets demand and the market clears. If the market-clearing price is below the cost of production, investment and production is reduced; if the price is very profitable for producers, investment and production increases. Wages get a lot of focus here: the solution to unemployment is inevitably lower wages, to clear the labor market.

Interest: Interest on loans and bonds are ultimately a price of capital. Much the same principles apply: the market interest rate leads to a clearing of the market between the supply and demand for capital. Lower interest rates increase demand for capital (more investment), and reduce supply (incentive for less saving and greater consumption). High interest rates discourage investment, but increase the returns on capital creation (savings).

Money: Money is basically neutral, in the Classical pre-1914 conception. Monetary distortion of various sorts can upset the equilibrium of prices and interest.

Now, look at what we have here. Prices and interest are basically self-regulating “equilibrium-seeking” mechanisms that can be left to the “free market.” Money is to remain neutral, basically on a gold standard system.

Recessions have basically become impossible, or at least, minor or unlikely. If there is a problem, then prices (especially wages) can adjust, and the system finds a new equilibrium.

We have just scrubbed economics of all kinds of real-world things that can certainly cause recessions and also long periods of stagnation and decline. Taxes and regulation — two giant areas of government economic policy — have disappeared from our model, either on the positive or negative side. Economists no longer recommend good taxation or regulation policy, or criticize bad taxation or regulation policy. It has disappeared. Also, government spending has disappeared. Welfare programs, public works, public education, or any other program that could conceivably have positive or negative economic effects, have disappeared. There is nothing to say whether a government spending program creates great benefits, or is a total waste, or in fact creates terrible consequences. It is all gone.

Education, the rule of law, judicial structure, ease of starting a business, the insane regulatory burdens of business today or a dozen other things that people discuss today in great earnest, have all disappeared from the study of economics.

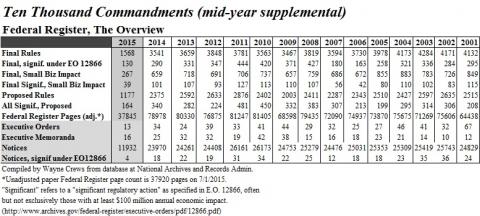

The U.S. Federal goverment: 4000 new rules per year.

Of course, any economist will agree, in casual conversation, that all of these things could have a meaningful effect. But, when push comes to shove, they stick to their mathematical models where all of this has been scrubbed.

Let’s look at some of the consequences of this, particuarly as it relates to the Great Depression, when it became important.

The Classical-leaning economists could see that the formation of prices and interest rates, in the 1920s for example, were relatively free and unmolested. This was not some kind of Venezuela-like statist failure. The money was soundly linked to gold. Thus, they concluded that there was no problem, and that “do nothing” was the best course of action.

The Keynesian economists argued that wages had become “sticky” due to unions refusing to allow wage rates to fall. Unemployment was caused by a “market that doesn’t clear” due to wage “stickiness.” The solution was a devaluation of the currency to reduce real wages, even if nominal wages were unchanged or rising.

The Keynesian economists also argued that economies could get themselves into extended slumps, and the solution was to depress interest rates. This would lead to more investment (and thus hiring of the unemployed), and also less savings/more consumption. This reduction in interest rates was basically to be accomplished via the printing press, and would thus be a roundabout method of currency devaluation, although the Keynesians didn’t talk about that much. Thus, via one justification or another, the Keynesians landed upon Money as their solution for the problems of Prices (wages) and Interest. The title of Keynes’ influential 1936 book was The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Keynes, and all his followers to the present day, are direct descendants of this “general equilibirum” stuff from the 1870s. That is why Keynesian economics was called “neoclassical economics” after WWII.

The Classical-leaning economists, after it had been shown that “do nothing” wasn’t working, then went looking for reasons why “do nothing” was a flop. Interest rates weren’t very convincing, because they were already very low in the Great Depression. (Today, the Keynesians talk about the “zero bound” for interest rates, which supposedly keeps the “market from clearing” during bad recessions.) If they didn’t particularly buy the “sticky wages” argument, and there weren’t obvious price controls and other such things preventing “equilibrium” in prices, then they were naturally led to believe that there was some kind of problem with the money.

The Classical-leaning economists were probably a little hesitant to embrace the “we need lower wages” argument, even if they agreed that unions caused some “wage stickiness.” (I personally think the “wage stickiness” problem is grossly exaggerated today, basically due to economists’ need to blame something within their very limited frame of reference.) Are you really going to say that “everything is fine, we just need people to be paid less”? Economic health had always meant higher productivity and higher wages. It was a loser on both an intellectual level and a political one. You could say much the same thing about interest rates, which collapsed during the Great Depression. Interest rates are not low enough? When they are at their lowest in history? There must be some other problem.

Thus we get a parade of Classical (anti-Keynesian) economists claiming one or another problem with the money, even though currencies around the world were on a gold standard system without any great problems or difficulties.

From this we get the “Austrian explanation of the business cycle,” which blames anything and everything on some kind of money/credit problem. It’s the natural conclusion if you don’t see a problem with the prices or the interest rates. Now, I agree that sometimes there is some kind of money/credit problem, especially in a floating fiat currency evironment like today. But, you can also have problems (or successes) from a great many other sources too. Also, any claim that there was some kind of vast money/credit problem runs into the question of: how did this come about under a gold standard system, which is supposed to disallow and prevent these kinds of problems? After all, the Keynesians (and other like them in the decades before Keynes) always complained that the gold standard system prevented them from engaging in the kind of activities that would create exactly the kind of money/credit consequences that the Austrians describe.

Rothbard, and many like him, claimed that there was some kind of great money/credit bubble, of Great-Depression-causing proportions, in the mid-1920s when currencies were soundly on a gold standard system.

Milton Friedman claimed some kind of vast money/credit contraction, of Great-Depression-causing proportion, again while currencies were soundly on a gold standard system.

A few economists, notably Gustav Cassel, claimed that there was some kind of gigantic change in gold’s value (a rise), thus causing money problems for all currencies linked to gold. But, gold had never shown any such behavior in the previous five centuries. Even the 1880s and 1890s, though difficult for commodity producers, were a time of great economic productivity and expansion.

Jacques Rueff, and some others, claimed some kind of vast disaster caused by the “gold exchange standard,” supposedly very different from the pre-1914 “gold standard.” But, we saw recently that they were actually rather similar.

June 26, 2016: Foreign Exchange Transactions and the “Gold Exchange Standard.”

October 14, 2012: Book Notes: The Age of Inflation, by Jacques Rueff

Besides, it was the rinkydink countries that had “gold exchange standards.” Britain and the U.S. didn’t. France began with one, in 1926, and then essentially went back to its pre-1914 policy.

July 27, 2014: The Bank of France, 1914-1941

Are we really going to blame the Great Depression on the fact that Poland and Yugoslavia had a “gold exchange standard”? Nobody blames Poland for causing the Great Depression.

Then there is the Blame France contingent, which Blames France because … well, they haven’t really figured it out yet. France accumulated a lot of gold … or “sterilized” something … or there was an “asymmetry” … or France had more gold than some other people, so there was a “disproportion,” which sounds like an “imbalance,” which sounds like it might be a problem … or maybe if we throw enough spaghetti at the wall, something will stick.

Read “The French Gold Sink and the Great Deflation of 1929-1932” (2012), by David Irving.

France was on a gold standard system. So was the U.S. and Britain, and everyone else. Basically, they had the same currency, just like the eurozone today, or countries which peg their currencies to the euro with a currency board.

Anyway, the point is that, the blinkered logic of Prices, Interest and Money led the Classical economists to Blame Money as a cause, and the Keynesians to Embrace Money as the solution. Some people were a little in both camps, notably Milton Friedman, who couldn’t really decide whether he was a Classicalist or a Keynesian (he was basically a Keynesian).

June 12, 2016: Milton Friedman Blames the Federal Reserve

August 12, 2012: The Dying Gasp of Monetarism

Keynesians have a little to say about nonmonetary goverment policy, but they are mostly interested in Spending. What the money is spent on is largely irrelevant. “Public works” sounds nice, and justifiable, although it does not take much probing to find that they Keynesians are completely disinterested in the question of which public works. The fact of the matter is, that any “public works” engaged in with the primary purpose of simply increasing overall spending is probably total waste. This is in part due to the fact that real public works projects of real value — I once used Hoover Dam as an example — typically have a multi-year planning process, while “stimulus” spending is generally aimed to create its effects within 6-12 months, and stretching over 12-18 months. Real things of real value don’t work like that.

February 22, 2009: Public Works Done Right

The focus on spending again comes from “general equilibrum” notions, basically the idea that “overall prices” are reflective of “aggregate supply” and “aggregate demand.” If “overall prices” are going down, as is common in an economic downturn with a stable currency, and if a big increase in supply is not obvious (“supply” is typcally shrinking in a recession), then “more aggregate demand” is the natural solution, following this line of logic. “Aggregate demand” basically means spending money, and since the government is about the only thing around capable of spending money in sufficient size, that’s where the focus goes.

Now think of that. All of government policy — taxes, regulation, tariffs, law and justice, welfare programs, public works and other public spending — just got turned into a single number of “spending.” There is really no place in this construct for any discussion of the actual details of taxes, or welfare programs, or anything. Even if you discussed it in depth for a month, and came to many insightful conclusions, there would be nowhere in economists’ equations of equilibrum to plug them in.

Economics today, among academics, hasn’t really advanced much, and is still stuck in the Prices Interest Money prison. One reason for this is that mathematics is still a big part of economists’ career track, even though they will have to abandon mathematics to incorporate all of the other important factors of economic policy. Maybe “abandon” is too strong a word, and “de-emphasize” would be better. But, I think you could actually “abandon” it, because I don’t think that any of the math, going back to Walras, has really led to any new insight. It has just caused problems.

That’s why the economists who do focus on all of these factors that fall outside of Prices Interest and Money tend to be outside of the “macroeconomics” circle, and are interested in developmental/regional economics, which tends to be more a matter of history and geography. When we start to talk about the economics of a real place and time, like China in the 1980s or India in the 1960s, then all of a sudden we are again talking about things like education or taxes or whether public investment to created real benefits or just crony payoffs, or whether tiny sole proprietorships have access to capital, or whether property is protected in court or confiscated wantonly by corrupt officials, or whether a country invites foreign direct investment or perhaps insists on domestic ownership of corporations, or how easy it is to set up a corporation, or a dozen other things.

Now, I know that every economist is going to claim that I am wrong, and that they are actually oh so very very concerned about all those things. Of course they are. They could not claim otherwise. Then, these very same people might turn around and suggest “nominal GDP targeting,” which is basically the claim that steady economic progress can be produced from monetary manipulation alone, and that all other factors are irrelevant.

March 24, 2016: The Simple Simplistic Simplicity of “Nominal GDP Targeting”

“Nominal GDP targeting” is really just a sort of automaticized version of Keynesian monetary manipulation. Keynesianism boils down to little more than money manipulation and government spending; and if, as a conservative, you don’t get very excited about deficit spending for no clear purpose except jiggering “aggregate demand,” then you are left with money alone.

The great advance of “supply side economics” in the 1970s was to finally bring back in all those things that got scrubbed from economics in the 1870s. Tax policy is a problem. Tariff policy is a problem. Regulation is problem. Existing welfare programs might be a problem. Maybe education is a problem. We don’t have to blame money for everything, for lack of a better solution within the Prices Interest Money box. The solution is: Tax reform. Tariff reform. Regulatory reform. Welfare reform. Education reform. Or, whatever else might be the problem, you just fix it.

Oddly enough, despite quite a lot of excellent work done on all of these topics over the past forty years or so, it still hasn’t penetrated the hermit kingdom of academia. They are still stuck in the Price Interest Money box.

But, even the Classical tradition, best expressed in the 1950s and 1960s by the “Austrians,” especially Mises and Hayek, was stuck in a similar Prices Interest Money box, and needed a major upgrade.

When you read the writing of any economist, from 1800 to the present, I invite you to ask: is this person stuck in the Prices, Interest and Money box? Just by asking the question, I think you will know the answer.