At some point, I’m actually going to talk about Robert Murphy’s book Understanding Money Mechanics. But, not yet.

March 30, 2025: Understanding Money Mechanics #2: Supply and Demand

March 23, 2025: Understanding Money Mechanics (2021), by Robert Murphy

So far, we’ve postulated a somewhat hypothetical scenario where all monetary transactions take place with silver coins, but the rest of the credit system (mostly banks but also all bonds, securitized lending, and so forth) is basically the same as we have today.

This is to illustrate the difference between Money and Credit, which have been confusingly mixed together basically since the late 19th century. The Money is silver coins, and they are very simple. They are just unchanging coins of silver. The amount of silver in them doesn’t change, but the quantity of silver coins does change, basically rising or falling depending on the aggregate desire of people (we are imagining a place like Britain in the nineteenth century) to hold silver coins. The value of the silver coins is the same as the value of silver everywhere. We are assuming that the coins are not debased or altered in some fashion, and that surrounding regulations and so forth (such as import or export controls on silver) are either nonexistent, or ineffective enough as to be not much different than if they were nonexistent.

We are assuming that the value of the silver coins is basically pretty stable, as was the case for many centuries in the past, but not so much after 1870. In the 1870s, silver’s market value was destabilized, for what was I think the first time in human history. Only gold today has the stable value characteristics that both gold and silver once had. So, we are imagining that these silver coins have a reliably (though not perfectly) stable value, much as gold does, and as silver used to have — much more stable, and reliable, than any fiat currency today.

Upon this very simple monetary system, we have built a superstructure of Credit, including banks and other forms of lending. This credit is NOT silver, it basically consists of forms of contracts, such as a loan contract, or a deposit contract (which is a type of loan contract with overnight maturity).

All of the elements of this system of Credit, or basically borrowing and lending, are determined by the aggregate decisions of individuals, to either borrow or lend, depending on their individual conditions. In aggregate, this becomes aggregate borrowing or lending.

Thus we see that the amount of lending, in an economy, depends on the specific conditions in the economy. It depends on whether someone wants to borrow money, for all of their individual reasons (including corporations), and whether someone wants to lend money to them, because they have the capital available (ultimately from capital creation or “savings”), because they determine that the borrower is a good credit, and because they don’t know of some other, better use of their funds.

There is some ratio between Bank Reserves (cash, in this case literal silver coins, either in a vault or in the vault of a Clearinghouse that the Bank is a member of), and either Assets or Liabilities of Banks, which must balance on their Balance Sheet and are therefore basically the same quantity. Both sides of a Bank’s balance sheet, the Lending (Assets) and Borrowing (Liabilities, mostly Deposits), are determined by many individual decisions, such as whether a Bank can find a borrower that it deems a good credit (underwriting), and whether a Depositor chooses to hold a Deposit at a Bank. The Bank Reserves are also determined by individual decisions, of Bank management, influenced by regulations, risk aversion, the size of Assets or Liabilities of the Bank, and the composition (types or character) of these Assets and Liabilities. For example, if a Bank had a lot of short-term lending, or marketable short-term securities like Treasury Bills, then it might not feel a need to also keep a lot of Cash on hand, since its Assets could be liquidated on short notice. Also, if a Bank did most of its funding with Time Deposits of one year or longer maturity, or similar bonds, it might also have less need for short-term cash. Or, vice versa.

All together, these many considerations determine how many silver coins the bank holds in a vault (or in its Clearinghouse account). When we take the aggregate desire (or “demand”) of Banks to hold silver coins, and add the aggregate desire of non-Bank entities to hold silver coins, we come to the total aggregate demand for silver coins, which, through the free import or export of silver, and the free operation of the Mint, determines the aggregate number of silver coins, or “money supply.” Thus the chain of causation is: Economic Conditions -> Bank Lending and Deposits -> Bank Reserves -> Demand for Silver Coins -> Supply of Silver Coins to meet this Demand.

Thus we see that bank lending, or bank deposits (two sides of the balance sheet) are determined by overall economic conditions. It is not some “multiplier” of the silver coins that the bank happens to hold. Nothing is “multiplied.” The chain of causation is from lending to reserves, not the other way around. If a bank doubles its reserves, or cuts them in half, this does not particularly change either Lending or Deposits, or the economic conditions that led to certain levels of Lending or Deposits.

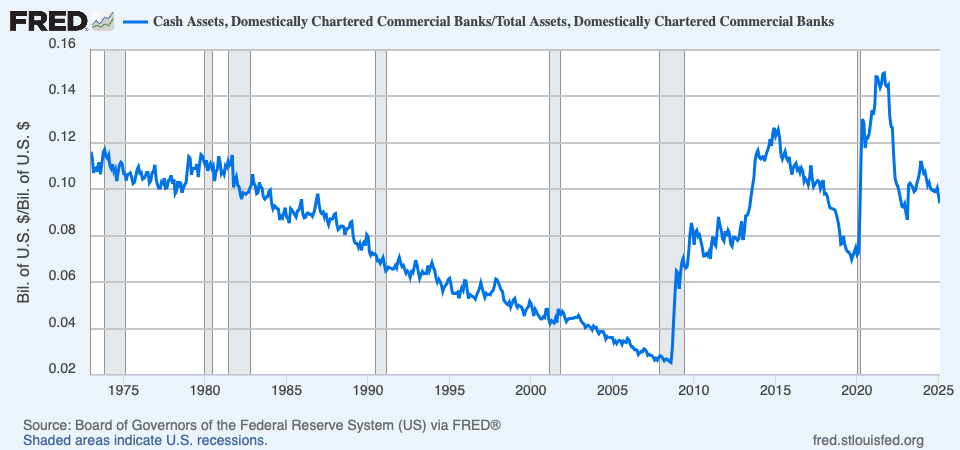

We saw that in actual fact, banks went from about an 8% reserves/assets ratio in the 1950s to under 0.1% in the 2000s, and this had no particular effect on either Lending or Deposits, both of which reflected economic conditions for lending and depositing. Then, they went from 0.1% back up to around 10%, and again, Lending and Deposits reflected economic conditions, not some “multiple” of Bank Reserves.

By the way, the ratio of Bank Reserves (at the Central Bank) to Total Assets of Banks was about 14% recently. I mentioned that this included Foreign Banks, which tend to hold a very high level of Reserves to Assets, basically because this is only one part of their consolidated global balance sheet. If we look only at Domestic Banks, it looks like this:

These are “Cash Assets,” which basically include Bank Reserves (held at the Central Bank), and also, short-term lending such as overnight lending to other banks or financial institutions such as brokers (“overnight lending” is basically the same as what we call a Demand Deposit). We see that “Cash Assets” were also about 10% in 1980, although the Reserves/Assets ratio was much lower than this. Banks were substituting overnight lending for Reserves, basically to chase profitability (a big deal in the early 1980s when overnight interest rates were very high). After 2008, these Cash Assets were almost entirely Reserves held at the Federal Reserve. We see that today it is again around 10%.

In practice, this change in Reserves would have to be accommodated by some change in other Assets and Liabilities. But, the original economic conditions that led to certain levels of lending or deposits are unchanged, so we should expect that the actual lending or deposits would also be basically unchanged. A good borrower that gets refused at one Bank, because that bank is building up its reserves, is accepted somewhere else, because banks recognize a good borrower when they see one. Or, perhaps, the interest rate rises a tiny bit, reflecting slightly less capital available for lending, which discourages the marginal borrower. Or, perhaps, with a little less capital available for lending, a Bank tightens its underwriting a little bit, requiring a higher loan-to-value or a higher income to support the loan, thus rejecting the marginal borrower. Or, perhaps, banks make Deposits more attractive, by offering a higher interest rate, or maybe some other thing, which allows them to attract more Deposits and fund the additional lending. In other words, economic conditions.

Now we understand both Money and Banking. We do not mix them in some confusing stew. The Money is very, very simple, and easy to understand. Banks are not hard to understand either. But, we come to conclusions that are very different than you are likely to find in any economic textbook, or indeed any alternative text, including all of the Austrian writings. If you think about it, and not for very long, I think you can see that this description here is correct.