We’ve been talking about “Understanding Money Mechanics,” by this time only vaguely related to a book by Robert Murphy of the same name.

April 6, 2025: Understanding Money Mechanics #3: Chain of Causation

March 30, 2025: Understanding Money Mechanics #2: Supply and Demand

March 23, 2025: Understanding Money Mechanics (2021), by Robert Murphy

Last time, I talked about the various influences that determine the amount of lending and deposits at banks (which must balance on the Balance Sheet), and their relation to Reserves, and where those Reserves come from.

Thus the chain of causation is: Economic Conditions -> Bank Lending and Deposits -> Bank Reserves -> Demand for Silver Coins -> Supply of Silver Coins to meet this Demand.

In a simple silver coin system, or actually in any proper system which fixes the value of the currency to silver (or, better yet, gold), the amount of money is determined by the demand for money, with the supply of money automatically adjusting to meet that demand, thus maintaining a stable currency value (stable relative to the benchmark, silver or gold). This is common today in the form of a currency board. I wrote a whole book about this, Gold: The Monetary Polaris.

Read Gold: The Monetary Polaris

However, that is not the way things are in a floating fiat system, as we have had since 1971. Here, the amount of money (base money) is determined by the whims of the central bank manager. It is not an automatically-adjusting system where supply meets demand, at a stable price.

But today’s floating fiat situation (you can hardly call it a “system”) is not quite a situation of complete discretionary abandon either. Typically, there is some kind of mechanism that, in practice, adjusts somehow so that the supply of money does meet the demand, at least crudely. The “demand” here is in the form of banknotes and coins in circulation, and bank reserves, which together constitute Base Money. Banknotes and coins do not change very much, or very quickly. Mostly, this takes place as a transaction with banks. You get some cash from an ATM. Normally, you would spend this and the cash would end up in the register at Starbucks. At the end of the week, Starbucks takes it back to the bank (deposits it in Starbucks’ bank account) and the bank puts it back in the ATM. However, some of this cash might not make it back to the bank. The total amount of banknotes in circulation increases, for whatever reason (maybe you bought some drugs with it). Thus, banks gradually pay out a little more cash (withdrawals from their deposit accounts in the form of banknotes) than they take back in. Banks get these banknotes from the Treasury or Mint. They pay for them with Bank Reserves. Thus, a Bank gets $1m of $20 bills, and the bank’s Reserves decline by $1m, as payment for the bills. The gradual increase in Banknotes and Coins is matched by a steady drain on banks’ Reserves, which then leads banks to seek more Reserves, which is the “demand” that leads to additional “supply” in our model

When banks are a little short of Reserves, they will tend to borrow on the open market, from other banks which might have an excess of reserves (excess according to their own judgement, which might be influenced by reserve requirements). This will tend to raise interbank short-term lending rates. Central banks, for some time, had some kind of interest rate target. When a rise in interbank lending rates indicated something of a shortage of reserves, central banks would create new base money, which would increase bank reserves. Thus, the “demand” was indeed resolved with more “supply,” in the context of an interest rate targeting system (with the rate of course changeable), not a stable value system.

Banks can also attract more Deposits, perhaps by offering a higher interest rate on them. These Deposits end up as additional Bank Reserves.

In practice, there were other mechanisms that also did the same thing, in a crude fashion. For example, when “demand” for Base Money was a little short of supply, there might be a noticeable rise in the value of the currency, compared to other currencies on the foreign exchange market. These changes in forex rates affect all kinds of transactions, both Trade and Investment. Usually, central bankers and related Ministries of Finance don’t want big, jarring changes in exchange rates with major foreign currencies. Thus, if a currency is rising (indicating perhaps demand in excess of supply of a currency), they might take an “easier” stance at the central bank, perhaps lowering interest rate targets, or raising Monetarist money growth targets, and one way or another increasing the base money supply, thus meeting the increased demand. The opposite might take place with a weakening currency.

Lastly, central banks also look at the CPI, gold and other commodity prices. When these indicate a “rising” currency, the central bank might take an “easier” stance, increasing base money supply and thus meeting the demand for base money. The opposite might take place for a “falling” currency.

All of these mechanisms are rather informal and chaotic. But, we know that the base money supply has increased, since 1971, and thus there was some kind of process that led to that increase. For the most part, until 2008 and even up to the present time, government financing was not a motivation. These informal processes accomplished a crude approximation of a more formal fixed value system, which rather more precisely adjusts supply to meet demand at the fixed value parity. Unfortunately, the general tendency of these informal processes, influenced by politics at every moment, has been an intermittent and chronic deterioration of currency value.

Thus, even in the context of floating fiat currencies, and central bank discretion over money base growth, in general the chain of causation remains similar:

Economic Conditions -> Bank Lending and Deposits -> Bank Reserves -> Demand for Base Money -> Supply of Base Money to meet this Demand.

Robert Murphy actually has an interesting chapter on this topic, which is Chapter 12: “Do the Textbooks Get Money and Banking Backward?”

Obviously our conclusion here, and also Murphy’s conclusion, is “yes, they get it backwards.” Murphy also cites an interesting 2014 paper from the Bank of England, “Money Creation in the Modern Economy” with basically the same conclusion.

Even in the condition of a floating fiat currency, which we’ve had since 1971, banks do their banking in much the same way as they did in the pre-1971 Bretton Woods gold standard era, and also, the era of silver coinage in the 18th century and all the centuries previous to that. Basically, their loan books reflect “economic conditions,” which, for a banker, means:

a) people want to borrow money, at a given interest rate;

b) people who want to borrow money meet various credit conditions, or underwriting standards

c) this loan can be financed at a spread between the funding rate (cost of deposits or other borrowing), and the lending rate (interest rate on the loan), that is attractive to bankers. There is an attractive Net Interest Margin.

The Liabilities side of a bank’s balance sheet, which must balance (banks need to have some kind of funding to make loans), we have factors such as:

a) people who want to keep deposits in the Bank, rather than spending their money on something else, or investing in some other kind of instrument, either debt or equity;

b) the interest rate that the bank pays to depositors, to make deposits more or less attractive; and the conditions of the deposits, such as time deposits vs. checking deposits, FDIC guarantees etc.

These conditions apply also in a fiat currency environment. Let’s imagine that the Base Money Supply were dramatically increased, due to the whims of central bankers. This would appear on Banks’ balance sheets as a Deposit on the Liabilities side, and Reserves on the Assets side. Now the Bank has additional funds with which it can make loans.

However, the bank might not be able to find borrowers that meet conditions a/b/c above. The amount of Bank Reserves changed, but the Economic Conditions did not. Therefore, the bank makes no new loans. The Bank may wish to simply keep the Reserves on the books, as perhaps the economic conditions are such that the Bank management wishes to take a more conservative stance. Management wishes to have a higher Reserve Ratio (ratio of Reserves to Assets or Deposits). Or, seeking profitability instead of security, bank managements might either loan the money out to other banks (an interbank loan), because maybe this other bank has lending opportunities to put this funding to work. As a surplus of loanable Bank Reserves hits the interbank market, the interest rate on Interbank loans might decline. This would tend to increase the interest rate spread between funding and lending, which makes making loans more profitable and possibly more attractive.

The Bank might also buy Securities, which typically means: investment-grade bonds, such as government bonds, MBS or other securitized lending, or corporate bonds. This extra buying would tend to raise the price and thus reduce the yield to maturity for these instruments.

The supply of Base Money, in our example, was increased somewhat wantonly by the Central Bank, in the contexts of a floating fiat currency. Maybe they got confused by some kind of NGDP Targeting argument, or MMT. (har) Since this additional Supply was not really motivated, and is not matched, by some corresponding increase in Demand, we might expect that the value of the currency will fall.

Just the fact that the value of a currency is falling at all, or the fact that the central bank has become entranced by NGDP or MMT nonsense, tends to decrease the Demand for a currency. This can even happen when there is no increase in Base Money supply at all! A currency just falls, for whatever reason (if it was obvious then forex trading would be easy). But if a central bank show no concern about this fall, then traders naturally conclude that the central bank is being somewhat irresponsible, or wishes to have a lower currency value. Thus, the currency falls further. This is actually quite common. So, we might have a condition of significant decline in currency value, even without any Base Money expansion.

My point here is that this macroeconomic turmoil, arising from changes in currency value, directly affects bankers’ and borrowers’ behavior. Maybe borrowers, perceiving that they can pay back a loan with money that is worth less than the money they borrowed, become more aggressive about borrowing, and are willing to accept a little higher interest rate, since the higher rate is still very minor in relation to the degree of currency decline or “monetary inflation.” As incomes or revenues rise due to inflationary factors, bankers perceive that borrowers have increased ability to pay back loans. Bankers do not particularly care if loans are paid back in currency that has lost value. That is the concern of depositors. Banks make money on the interest rate spread; and if the spread is sufficient, and the credit risk tolerable, they make the loan. Thus, more loans get made.

Again, the chain of causation arises from “economic conditions,” this time in a situation of macroeconomic disorder and monetary inflation. The additional Money Creation by the central bank did not “force” bankers to make more loans. But, the macroeconomic conditions arising from this wanton money creation did change bankers’ behavior.

Let’s say that the value of a currency fell, considerably, but there was little actual money creation. This is what happened in 2001-2008; and also, 1970-1980.

Now borrowers and bankers have a similar set of influences as before. Borrowers perceive that borrowing money, at a low interest rate, when the value of the currency is declining, is an attractive proposition. Bankers determine that borrowers are likely to be able to pay these loans back, in an inflationary environment. Thus Bankers want to make more loans.

Bankers will then seek funding for these loans. There is now more “demand” for short-term funding (probably Deposits). Maybe the short-term rate of interest rises. Central banks may then respond to this, via the mechanisms described earlier, thus creating additional Base Money Supply to meet this increased Demand, which arises due to the inflationary monetary conditions (declining currency value).

Once again the chain of causation begins with General Economic Conditions, which then determines borrowing and lending. Note how, in this example, a decline in currency value, perhaps and in fact quite often without significant “money creation,” prompts borrower and banker behavior. This behavior leads to certain conditions (perhaps higher interest rates) that central banks then respond to, perhaps by creating more money. The money creation actually follows after the currency decline.

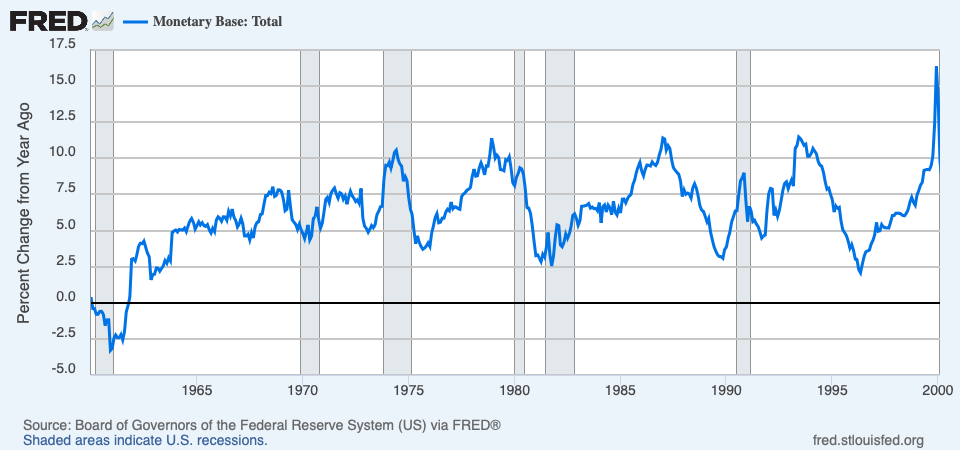

Here we see that “money creation” (base money supply) was quite modest in the early 1970s, basically in line with the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s. Nevertheless, there was a tremendous decline in currency value, with the dollar’s value collapsing from $35/oz. in 1970 to about $180/oz. in 1974.

Here is the Fed Funds Rate, the rate at which Banks make loans to each other (or basically the Deposit Rate for banks).

We can see that the Fed Funds Rate shot up in 1973, to over 10%. You could say that the 10% YOY growth rate of the Monetary Base, in 1974, was obvious “too much money printing!,” although I would also say that 10% is not really that much more than 5% or 7%. Nevertheless, it is a standout figure. Basically this was coming in reaction to the much higher interest rates that preceded it. In the process of keeping the short-term interest rate from rising to what seemed too high a figure (because everyone was complaining about short-term interest rates, among the highest sustained rates in the history of the United State up to that point), the Federal Reserve created what was actually a little teeny bit more money. Money creation actually followed the changes in the value of the currency.

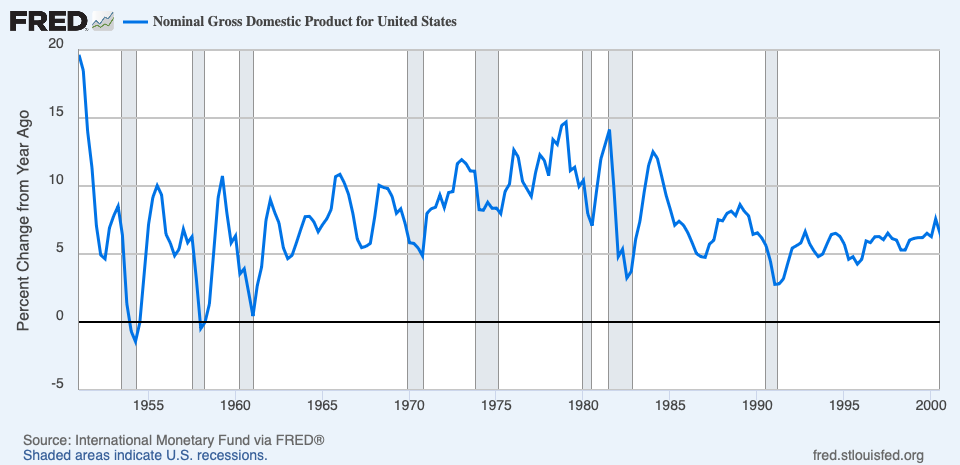

Since Nominal GDP was actually rising at a fast pace during this time, >10% YOY due to the monetary inflation, Base Money Growth of only 10% probably seemed quite restrained, by the Monetarist conventions which were popular at the Federal Reserve in those days.

Thus we see that our Chain of Causation is not so much different than in the original Silver Coin example, with Money Creation crudely and roughly following Demand for Money, as expressed by interest rates, nominal GDP and other factors, in the context of the monetary inflation of the early 1970s.

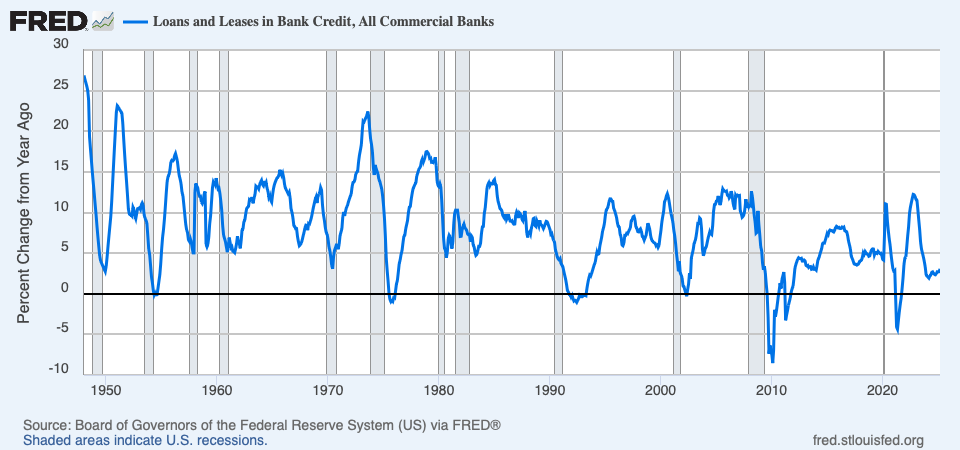

Here is bank lending:

We can see an explosion of bank lending in 1973, basically as people figured out that they could borrow in depreciated currency. A similar burst took place in the late 1970s. In this particular example, I see: a decline in currency value (vs. gold) largely without much expansion of Base Money; an explosion of lending motivated by this currency decline; and Base Money largely following along afterwards, to accommodate (even rather cautiously) this expansion in banks’ balance sheets.

Economic Conditions -> Bank Lending and Deposits -> Bank Reserves -> Demand for Base Money -> Supply of Base Money to meet this Demand.

This is basically why Central Bankers are always saying that they are not causing monetary inflation, but “fighting” it.

It is worth thinking through all these things a little bit. It is the opposite of what you would read in an economic textbook. But, I think you will recognize that this is what is really happening in the real world.