(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on April 25, 2021.)

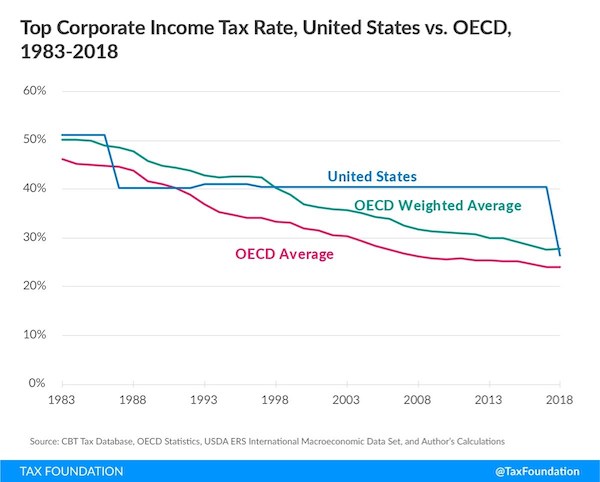

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen presides over the “Made in America Tax Plan,” which includes an increase in the Federal corporate income tax rate from 21% to 28%. Combined with State and Local corporate income taxes, the OECD calculates that the effective statutory rate right now is 25.77%. Adding 7% to this would presumably raise the total to 32.77%, which would just beat out France (32.02%) for the title of: highest corporate tax rate in the OECD.

The current corporate tax rate for Spain is 25%; Britain, 19%; Sweden, 21.40%; Switzerland, 21.15%; Poland, 19%; Ireland, 12.5%; Hungary, 9%.

Taxes are high in Europe. But, these are mostly broad, flat payroll and consumption taxes. They are much too high. Taxes on capital and business, in Europe, are generally lower than in the U.S. This is one reason why the economic situation in Europe is not as bad as some might expect, even with high overall taxes.

“[A]lthough U.S. companies are the most profitable in the world, the United States collects less in corporate tax revenues as a share of GDP than almost any advanced economy in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).,” the Treasury complains in the first page of its attempt to justify a higher corporate tax rate.

This is the natural outcome of decades of very high taxes in the United States. Corporations figured out a long time ago that they could pay lobbyists to pressure Congress into adding endless deductions and exemptions, and thus avoid taxes that really were too high. The result of all this, after decades, is that tax revenue was very low, as a percentage of GDP. High tax rates produce low revenues. This is a pattern that we’ve discovered over and over again, throughout history, as I described in The Magic Formula (2019). We should have learned this by now.

In the rest of the world, lower corporate tax rates have been accompanied by higher revenues, as a percentage of GDP. Probably, these lower rates have been accompanied by tax simplification, or the reduction and elimination of the various ways that corporations (quite rightly) sought to avoid past tax rates that were way too high. Britain got more tax revenue in 2019 (2.49% of GDP) with a 19% tax rate, than it did in 1978 (2.19%) with a 52% tax rate. Britain also got more than the U.S. did in 2016 (1.95%), when the combined U.S. rate was 38.92%.

These countries did not only benefit with a higher tax revenue/GDP. GDP also probably rose as a result, since lower tax rates tend to produce a healthier economy. As more people are employed at higher wages, in a healthier economy, not only do corporate tax revenues increase, but tax revenues from all sources. Also, pressures to increase welfare-type spending go down. More revenue and also lower spending. Europe proved this in a big way in 2013-2014, when lower tax rates across the continent helped produce an economic recovery, higher tax revenues, and smaller deficits.

President Trump took a big step toward remedying this situation when he led the reduction in corporate tax rates in 2017, which reduced the Federal tax rate from 35% to 21%. However, the existing deductions and exemptions were not reformed much. The result was a collapse in revenues. This was not such a bad thing. Those corporations that did not pay much tax before 2017, taking advantage of an overcomplicated tax law, did not pay much afterwards. The difference was with those companies that were faced with paying the full rate. They enjoyed a big benefit. Nothing wrong with that. Healthy corporations lead to a healthy economy. That’s why the tax rate in Britain is only 19%.

But, it amounted to only half of a reform. There should have been some move toward eliminating excessive deductions and exemptions, and broadening the tax base.

The result of all this is the persistent impression that many corporations are paying less tax than they should — in many cases, zero, or nearly zero. One effect of this is that it tends to favor old, established companies, that have lobbied for tax advantages over a period of decades. Young companies end up paying the high statutory rates. The result is that innovative, high-growth companies are unnaturally suppressed. (Old, established companies, that are not paying much tax, actually like this.) The cure for this is not a higher tax rate, but a reform of the tax code that eliminates the exemptions and deductions that have built up, as an inevitable result of tax rates that were too high.

The natural conclusion of these strategies is a Flat Tax. This would have the lowest-possible rate, on the broadest-possible base. Commonly, this is known as the “VAT base,” which taxes profits before payments of interest. This would eliminate a highly distortive element of the present tax code, that unnaturally favors debt capitalization instead of equity. The result is that corporations tend to be overly indebted, and thus prone to bankruptcy. Also, it has led to the rise of the leveraged-buyout private equity industry, which has amounted to balance sheet tricks that provide no benefit to either corporations or employees. Another aspect of the “VAT base” is that corporate capex would be effectively expensed in the first year, which is a big incentive toward more investment, which means more jobs and higher wages. However, since there would be no depreciation, taxes later would be higher. The end effect is more investment, more jobs, and higher taxes paid on the profits of those new investments. It’s a winner all around.

We’ve been discussing Flat Taxes and FairTaxes since the 1980s. But, some countries have actually gone and done it. One is formerly-communist Bulgaria, which instituted a 10% Flat Tax in 2009. Tax revenue/GDP from the 10% Flat Tax was 2.24% of GDP in 2016, higher than the U.S. with its near-39% effective rate, and higher than Bulgaria had in 2000 when the rate was 40%.

In the 2016 election, Donald Trump proposed a corporate tax rate of 15%. It would make the United States one of the most business-friendly places in the world. Today, if Yellen and Biden really want to remedy the problem of low tax revenue/GDP, and many corporations that take advantage of tax loopholes to pay no tax at all, they would not only embrace Trump’s 15% proposal, but combine it with an across-the-board reform of the corporate tax law, along Flat Tax principles.

All the evidence we have today, from around the world, suggests that this tax reform, a Flat Tax with a 15% rate, would create more revenue/GDP than the U.S. got before 2017, when the combined tax rate was nearly 39%. It would eliminate the huge disparities that has some corporations paying taxes that are really too high, and some highly profitable corporations incongruously paying almost none at all.

But, the fun wouldn’t stop there. As the U.S. becomes the best place in the world to do business, more business is done there. More capital is invested, and more jobs are created, at higher wages. This would increase tax revenues across the board, including personal income taxes, payroll taxes and sales taxes. This is what I called the “Spiral of Success.”

With the U.S. outcompeting everyone, Yellen would soon give up her “global tax harmonization” talk. The U.S. is not interested in “harmonizing” with Socialist Europe. (Or, having them “harmonize” with higher tax rates in the U.S.) We are interested in eating their lunch.

I know all this seems like so much pie-in-the-sky fantasy now that Leftist elements seem in control of the U.S. government — not only now, but, through continued voting fakery, into the forseeable future. Debating about tax rates up and down, as we have done endlessly for the past seventy years, might not seem very relevant. We wonder whether a Constitutional Republic remains at all, or if the U.S. becomes part of a globalist “Great Reset” ending in grim Hunger Games serfdom sprinkled with “Green New Deal” propaganda.

But, out of this, might come a chance to actually make these kind of big changes. Japan’s dreams of Asian Empire died in 1945; but, then they had to come up with something new. It worked! We should have a good idea of what we want, because at some point, we might have a chance to get it. It seems like we have spent decades arguing these finer points of things that never happen. But, sometimes, things happen. Then, you won’t have decades to talk about the finer points anymore. You will have to act fast — on convictions that you have formed up in years previous.

Not only that, but the conviction that things could be better — not just “better” in a vague sense, but in specific ways — is what propels people out of apathy. It makes them more than simple sheep to be herded.