Until now, I’ve mostly dealt with important but, in my view, secondary aspects of the topic of Economic Nationalism. Having now addressed that, we can turn to what I consider the core of the matter, without (I imagine) being distracted by secondary concerns.

These basically fall into two categories — the Capital-Labor Ratio, and issues of Nationality that are not economic.

In the 19th century, Ireland was very poor, and many Irish people immigrated to the United States. This Irish immigration, beginning in response to the Irish Famine of the 1840s, was the first major wave of immigration since the founding of the United States. Before then, for about fifty years, there was almost no immigration, which tells you that the United States was never supposed to be a “melting pot.” All of this “give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses” stuff was pro-immigration propaganda written by a Jewish Zionist immigrant from Russia, who wanted the doors to remain open to Jewish Zionist immigrants from Russia, and which was unrelated to the making of the Statue of Liberty itself, which of course took place in France. Immigration from Russia at the time (the 1890s) was rather controversial. Along with new immigration from Italy and elsewhere, it was the first time in US history that there was significant immigration from outside Great Britain, Canada and Germany. Ireland was, in the 1840s, part of Great Britain (Ireland became independent in 1921), so basically Irish immigration was British immigration, and the Americans were British, in fact British colonists only a few decades earlier.

Why did these Irish come to the United States? Basically, it was the Capital-Labor ratio. There were too many people in Ireland compared to the Industrial Capital (jobs), or the basic natural capital of arable land or exploitable natural resources. In other words, they were poor. Irish people leaving Ireland improved the Capital-Labor ratio of Ireland (less Labor); and also, the Capital-Labor ratio of those Irish immigrants, who enjoyed more employment opportunities and cheap land (more Capital). Why does anyone employ someone else? Basically, it’s because there is some Capital, which needs Labor to be productive. This Capital might take the form of a factory, or a retail store, or a truck, or a farm.

March 30, 2008: The Capital/Labor Ratio

July 24, 2011: The Capital/Labor Ratio #2: How To Create Jobs

January 5, 2017: The Problem With Free Trade: Much More Labor, Not Enough Capital

January 24, 2021: Adam Smith on the Capital/Labor Ratio

When Capital is scarce, wages are beaten down to low levels; and also, some people don’t get a job at all. They are basically without Capital, in the form of an employer. These people typically end up working at some low-Capital job for low wages. Something that does not require a big organization, education and training, or capital equipment. Basically, unskilled services. They become lawnmowers and dog walkers. There is widespread “underemployment.” People could be more productive, but they aren’t.

When Labor is scarce, there are more jobs than people. Wages are bid up; and everyone finds some productive enterprise, that makes use of their inherent potential.

The second condition is good for society as a whole. But, it also means that you will have to pay higher wages for worse employees — the Bottom 30%, and even the Bottom 10%.

February 7, 2021: The Bottom 30%

June 9, 2023: When Is Wealth Inequality a Problem?

This is good not only because the Bottom 30% benefits from higher wages, but also, because, by working at a higher-paying and more demanding job (not a low-capital, low-skill service), the Bottom 30% also learns hard work and self-improvement, and all the other virtues that come from what amounts to a broad middle class.

In the last century, we generally agree that the most prosperous period was the 1950s and 1960s, a time of a broad middle class. Why?

This time period came after a long stretch of limited immigration. After the immigration boom of the 1890-1910 period, immigration was choked off and almost ceased completely during the Great Depression.

January 31, 2021: A Brief History of US immigration

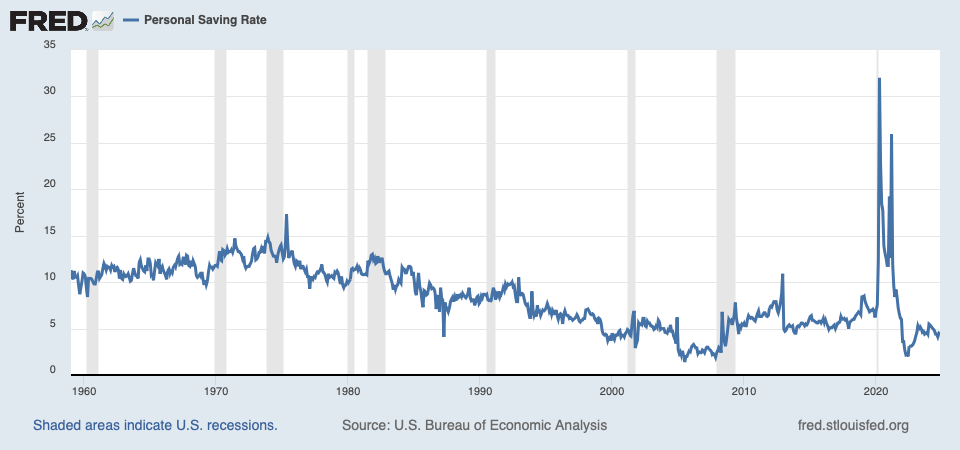

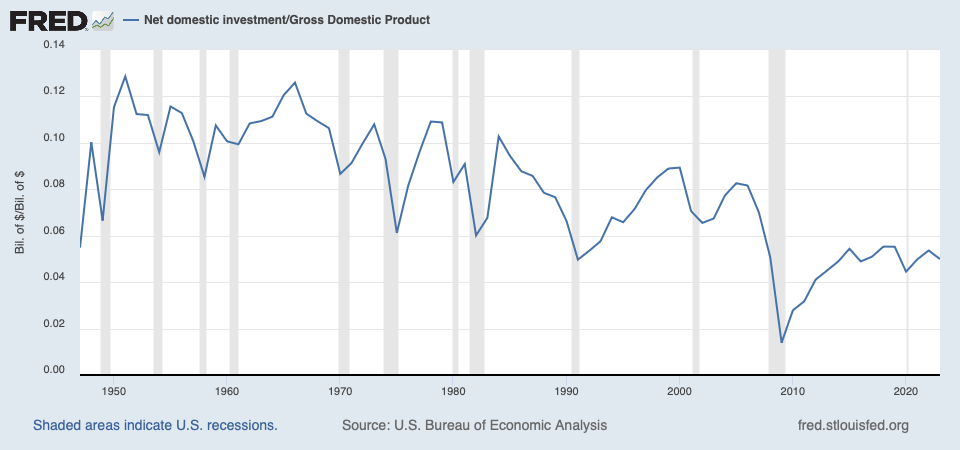

Also, during the 1950s and 1960s, there was a relative abundance of Capital, in the form of a high rate of savings and investment.

With a high level of personal savings, small government deficits, and a high level of reinvestment of corporate profits, the overall Net Investment/GDP ratio was quite high.

December 1, 2024: Economic Nationalism: Savings and Investment

There was more than twice as much net investment/GDP in the 1950s and 1960s, compared to today. Basically, this means new high-paying jobs — high-productivity jobs that arise from capital investment, such as a new factory or business of some sort. Not low-skill, low-capital jobs for meager pay. And, there was almost no immigration to compete for these new jobs.

This was a time when a high school graduate could get a pretty good job at the new factory in town. They still needed to have the basic skills to do the job, but they didn’t have to compete with many other people, driving down wages.

Businessmen recoil at the thought of paying employees more, basically because of competitiveness issues. In a competitive industry, a rise in costs by 10% or 20%, that a competitor doesn’t have to pay, doesn’t make the business 20% less profitable, it might drive them out of business altogether.

However, when all the businesses face the same limitations, then it is not so important. No one business has a competitive advantage. They all have to pay higher labor costs. This is passed on to customers. More money flows from those that have money (customers) to the workers. The result is a “broad middle class,” and the disappearance of both the “working poor” and also, the non-working poor.

Basically this is a sort of “redistribution of income.” The Bottom 30% (more like Bottom 70% actually) gets paid more, and the Top 10% has to pay more. Exactly as it should be. But, we don’t want to penalize the Top 10% either. We want a healthy economy and expanding businesses which also make the Top 10% (and Top 0.1%) more wealthy along the way, even as income disparities lessen. Everyone gets rich together.

Businesses would face higher labor costs than overseas competitors. But, the whole world has always had lower labor costs than the US, even in the 18th century (which is why people came from Scotland to America). There are hardly any US businesses today that compete on low labor costs. Is anyone trying to make shoes more cheaply in the US than factories in Indonesia and Vietnam? They might compete on low production costs — but these low production costs mostly come from very high levels of automation (capital investment), with the big machines overseen by a small number of highly trained and highly paid employees.

This happy outcome, of a “broad middle class,” was, as has always been the case, undermined by businesses searching for lower labor costs. The booming US economy of the 1880s led businesses to push Congress to allow more immigration. This was nevertheless limited to those groups most closely aligned with Americans — British, Scots and Irish (all part of Great Britain), Canadians, and Germans. (English are ancient Germans.) Later, this spread — controversially at the time — to groups that did not have as much ethnic connection to the Americans, including Russians, Italians, Poles, Swedes and some Chinese. There was, throughout this time, little (legal) immigration from Latin America, even though Mexico was always sitting there south of Texas, and was always populous going back even to the Aztec period.

In the 1960s, again a booming economy and tight labor market led businesses to push for more Labor availability, with the Immigration Act of 1965. This opened the door for Latin American immigration, both legal and illegal.

The Economic Nationalists today sense all these processes, but they don’t have good words for them, or a theoretical base of understanding. Nevertheless, they have the right instincts. The solution to returning to more of a 1950s-1960s state of a Broad Middle Class is a tight labor market — you could say, artificially tight — which arises from two things: Limits on Immigration (and today, expelling all the illegal immigrants), and also, much higher levels of Savings and Capital Investment (creation of new high-productivity jobs), returning again to the levels of the 1960s. These would provide, you could say, “artificial advantages” to the Bottom 30% of the population, which is as it should be it seems to me.

Businesses would complain. But, the 1960s were not exactly bad for business either. Since we want a prosperous economy with strong expanding businesses and lots of capital investment, this also implies a business-friendly environment both in terms of taxes and also, regulation. I think there is a political tradeoff here: businesses won’t have the access to cheap labor that they have enjoyed. They will have to hire Americans, and pay them more. But, on the other hand, they will have lots of capital, and a very business-friendly environment to make productive use of that capital, by building lots of successful new businesses and employing a ton of people.

If I were a businessman, I would take that deal.