I wanted to spend a little more time with Classical Economic Theory and the Modern Economy (2020), by Steven Kates. This is really a worthwhile book, with many insights.

July 9, 2023: Classical Economic Theory and the Modern Economy (2020), by Steven Kates

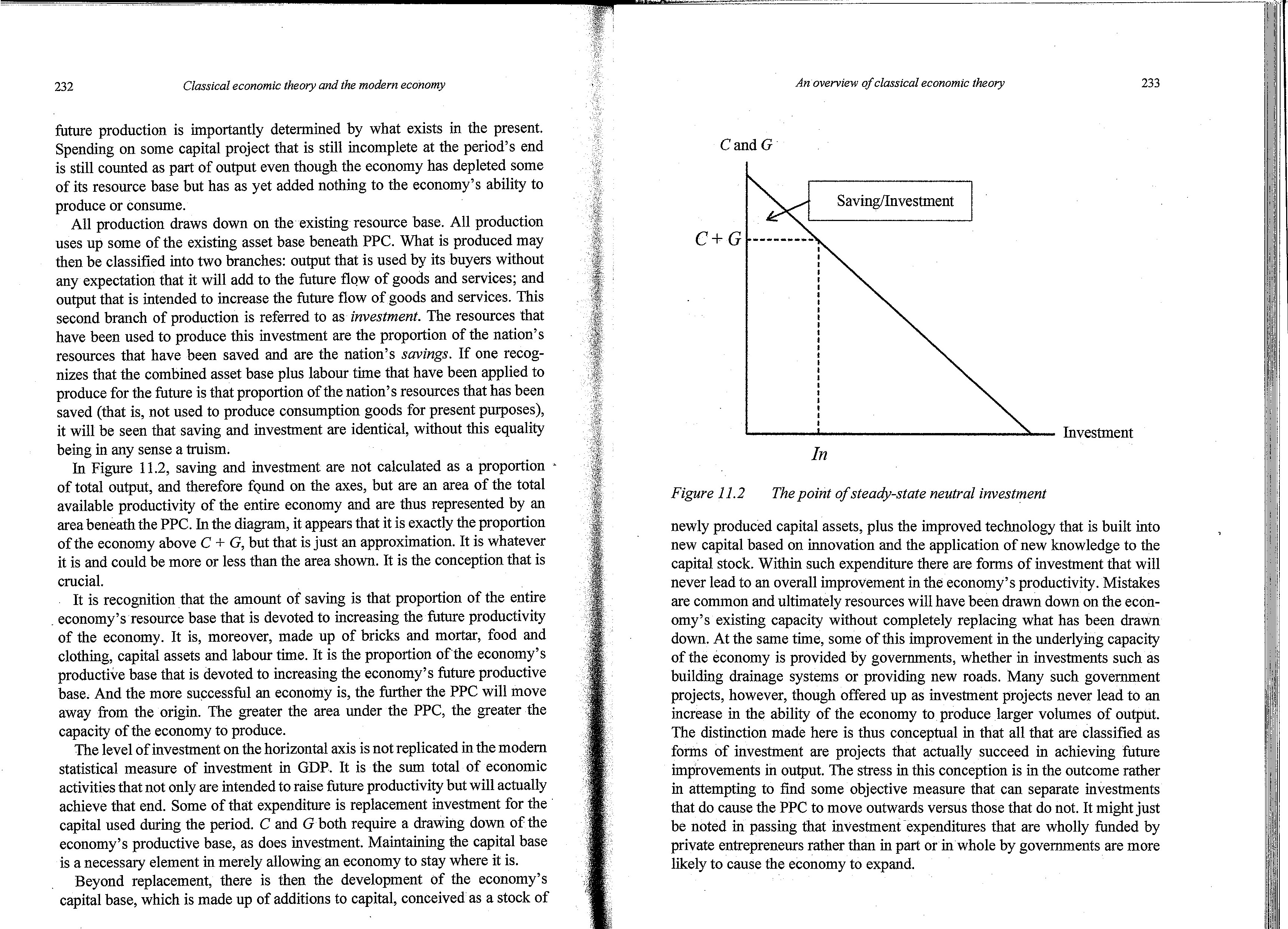

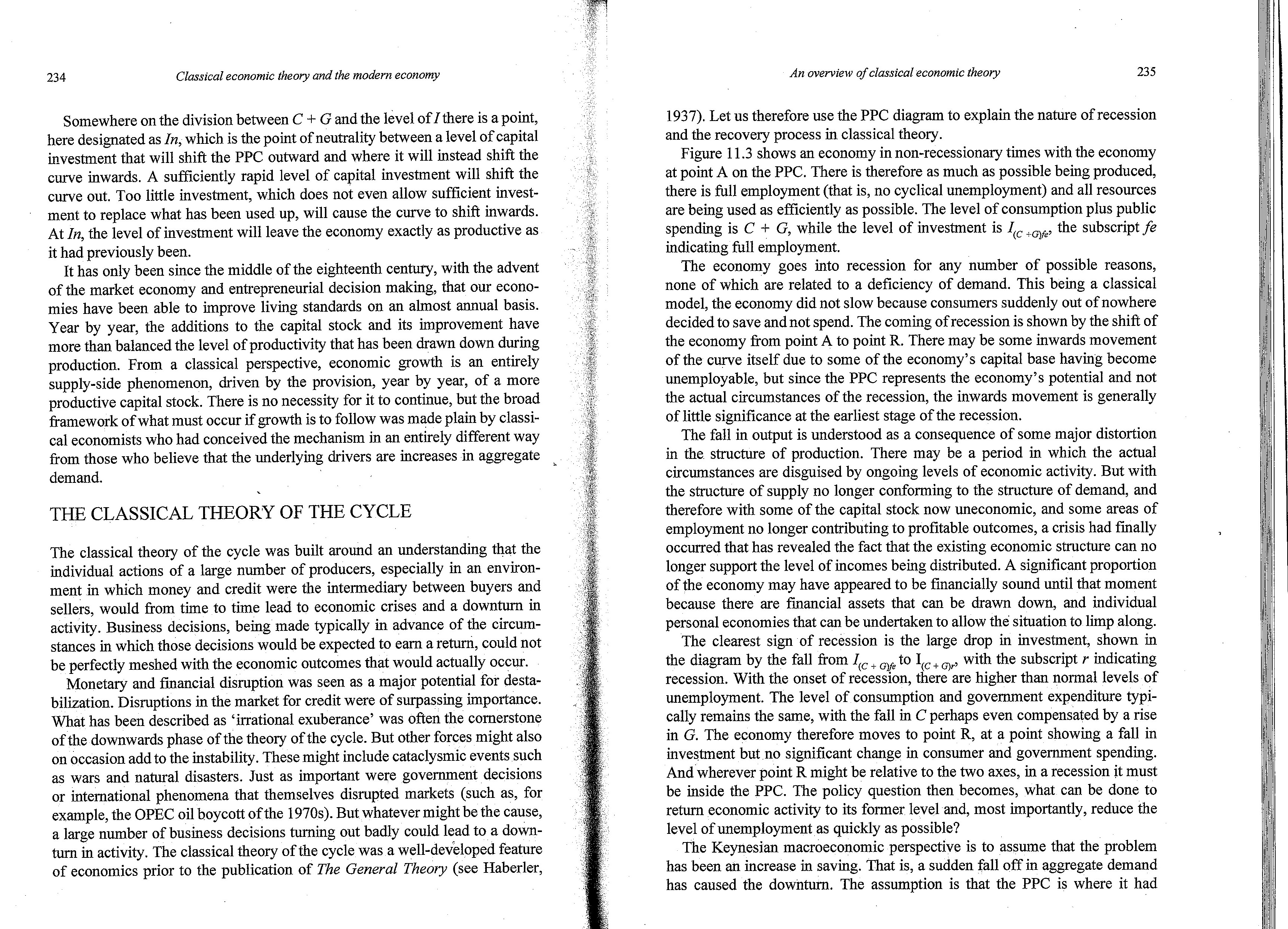

Here I will simply reproduce one of the most compact and illuminating sections of the book, which highlights some of the errors of both the Keynesian and Marginal Revolution-era thinkers, and also gives a brief summary of the Classical view of recession and business cycles. This is informed by quite a lot of reading into many of the key Classical texts, up through the 1930s and 1940s.

There are a couple interesting things here:

I agree with the basic conclusions of the Classical thinkers, as represented here, which is that a “business cycle” or recession can be related to an imbalance between the things that are being offered in the market, and what people want. This can be exacerbated by a credit cycle, which is mentioned here also but which does not get much more commentary. These are phenomenon which can happen with an environment of good economic policy, and no policy changes — in other words, arising from the free enterprise process itself, without government influence.

However, we can also see a rather big missing element — basically, government policy, for good or for ill.

Good government policy tended to be assumed in the 19th century, because taxes were low and money was linked to gold. This “government policy” includes taxation, regulation, spending programs of various sorts, and of course also monetary factors. We see more commentary on monetary factors from the Austrian group, probably since Austria itself had a mildly floating currency in the late 19th century before returning to gold in 1896. Also, there were other episodes of floating currencies during the 19th century, including the US in 1861-1879.

March 5, 2017: Floating Currencies of the Classical Gold Standard Era, 1850-1914

Of course all this got a lot more serious during and after World War I, when all the world’s major currencies floated.

The Great Depression was the ultimate expression of bad economic policy, in every way. Although Kates goes into the errors of the Keynesians in great detail, arising from their interpretation of the Great Depression, he offers few insights into the failures of the Classicals, which was basically a failure to recognize, and fix, bad economic policy. Indeed, many of the problems were caused by Classical/Conservative-leaning people themselves, who prompted both the worldwide rise of tariffs (by the Republican Party in the US) and the big tax increases seen in nearly all developed economies, in response to budget deficits arising from recession. This was not “doing nothing,” it was actively making things worse with huge new policy changes. Of course this was followed up by more of an interventionist/socialist approach by people like Roosevelt, and his disastrous National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933.

Since then, the more right-leaning or “Classical” groups, notably the Austrians and Monetarists, have indeed looked for Government Error during the 1930s, and found it — almost entirely in monetary policy! This is really perverse, since there was no problem with monetary policy that I’ve found, before the big obvious devaluations such as Britain in 1931. You could throw darts nearly anywhere and find some kind of big obvious problem, except for that — which is exactly what the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and other major central banks said at the time. This “blame money” habit came out of the Classicals’ economic conception of the time, following WWI when monetary issues became a big deal. For example, we have Ralph Hawtrey in 1922:

“The trade cycle is a purely monetary phenomenon.”

Riiiiight.

So we see the “Classical”-flavored economists still getting it wrong, up to the present day. The primary reason for this is that their economic theory did not really have any place in it for economic problems arising from bad government policy, outside of monetary policy. In other words, the “Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle.”

The NIRA, and other major factors of the time, were beautifully explored by Amity Shlaes in The Forgotten Man (2008), and also, FDR’s Folly (2003), by Jim Powell. Reading these, nobody would be surprised that such policies would have a negative, maybe very negative, effect. But, this tends to be acknowledged, and then forgotten. It is, rather bizarrely, not integrated into people’s economic “models,” not just the mathematical kind but even the more informal sort, such as the “Classical Theory of the Trade Cycle” that we have described here. People nod and say: “Yes, obviously,” and then go on to blame the Federal Reserve for everything.

Kates’ book is really well done, with much valuable research and important insights, and very little to criticize. If it seems that I am here criticising the omissions of the “Classical Theory of the Trade Cycle,” it is only because Kates expresses it so clearly, based on long and intensive investigation, that its insufficiencies become obvious. I am looking forward to reading more of Kates’ books.