A reader complained that I have not included Hillsdale College in my discussion of college alternatives. This is a valid complaint, so today, let’s take a quick look at Hillsdale, especially for those readers of this series who are not familiar with it.

Hillsdale is a rather wonderful, and underappreciated, college in Hillsdale, Michigan, known for its conservative, Constitutionalist curriculum. It would serve as a good model for U.S. colleges as a whole. I think that, to a large degree, the Hillsdale model was the model for U.S. colleges as a whole. Other colleges changed, after 1960, while Hillsdale did not.

I haven’t included Hillsdale because it does not fit our theme of “building your own college,” possibly beginning with one Teacher and one Student — Mark Hopkins and a Student sitting on a log. Hillsdale’s curriculum is admirable on many levels, but its organization and teaching method are much the same as any large institution today. The methodology is Lectures in a Class with a Specialist. The organization of the institution is of Specialists in Departments — the Prussian University model. Hillsdale devotes half of its students’ time to a course of required Core courses in Western Civilization and Liberal Arts. Then, it proceeds to a variety of specialist majors. This is natural for a larger institution, which can support a variety of majors. But, it differs from our vision of a smaller institution that is unified by a course of study common to all, possibly taught by Teachers who are mostly generalists, and familiar with the entire course of study, and who are themselves examples of that philosophy. (To their credit, the professors at Hillsdale probably do share the background that is expected of undergraduates.)

As an institution, Hillsdale is not a model that can easily be replicated. If you were going to Build Your Own Hillsdale today, it would probably cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and it would probably have, inherent within it, all the expense that characterizes nearly all colleges and universities today. Hillsdale is probably a very good example of how an existing college of roughly the same size can reorganize itself to become much more relevant, useful, and beneficial to its students, which might mean the difference between institutional survival and failure. It is a good example of the kind of institution where Conservative parents should be sending their children, instead of the Cultural Marxist indoctrination centers that they are sending them to now.

But, converting an existing college to the Hillsdale model would not be as easy as simply cooking up a new curriculum. To really succeed at this, you would probably have to fire 70% of the professors (Leftist garbage) and 70% of the administrators (useless baggage). Not an easy thing for an institution. It would require a whole new leadership, backed by the Board of Trustees to undertake an unprecedented purge. But, many of the existing students, already happy with their half-completed Leftist indoctrination, might not be so happy with their new college either. We saw that St. Johns College actually did something like this successfully, in the 1930s, so it is possible. But, for most institutions, it will likely be a process of disintegration and recreation from raw materials.

The quality of Hillsdale’s courses really is quite good. You can try some of their online courses here:

Click for Hillsdale College’s online course offerings

Every Hillsdale student completes a unified fourteen-course series in Liberal Arts, which constitutes about half of their four-year curriculum. Here it is:

It is interesting that, when you sit down and ask the question: “What is it that we think Students should study?” leaving this open-ended with a great variety of possible answers, the answer is nevertheless almost always the same. History, government, literature, arts. It is not so much that there aren’t many other worthwhile things to study; but that you should absolutely study these things, and that fills up our time. You can also study other things, some other time. Hillsdale also has four courses in Science and Math, which I consider a necessary part of the Liberal Arts curriculum, but which could be completed in high school. Sports are on the curriculum. Nearly all educational thinkers (we will look at some later) have included daily exercise and a healthy diet as necessary elements of their educational ideal.

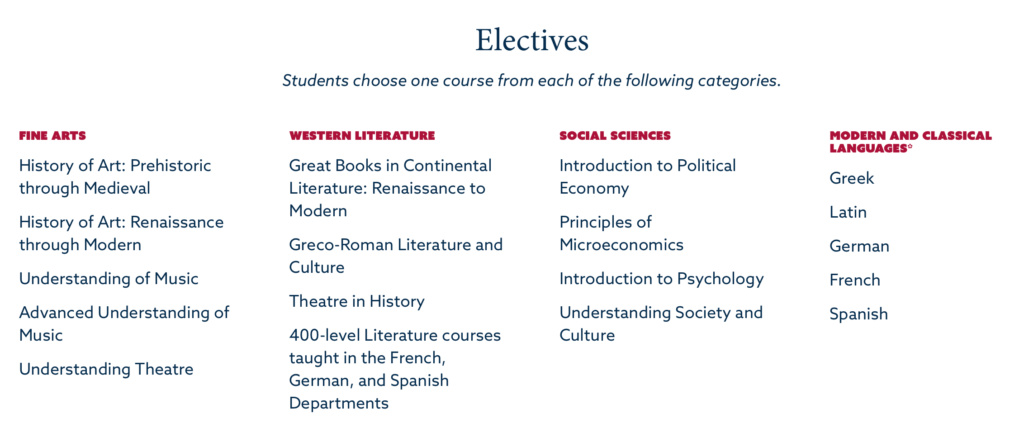

There is also a Liberal Arts elective:

While I appreciate this program very much, I sense that it is much less ambitious than the program I laid out myself. I suspect the “Great Books in the Western Tradition” falls quite a bit short of the fifty-volume Harvard Classics, and that “The Western Heritage to 1600” doesn’t include as much as Durant’s eleven-volume Story of Civilization. But, my program is for ambitious hardasses. You would have to work to get it done.

Then, the Hillsdale Students split up into Majors and Minors. These are pretty common mainstream offerings, with a mix of vocational training (majors in Accounting, Sports Management, Pre-Med), specialist Math and Science (in effect, vocational training for techies), goofy stuff (Theatre), foreign languages (Spanish), and more Liberal Arts (History). So, Hillsdale students really get about two years of real Liberal Arts (non-vocational) study, and some opt to continue to four years with some specialization.

All in all, it is a far better offering than nearly all colleges and universities today.

* * *

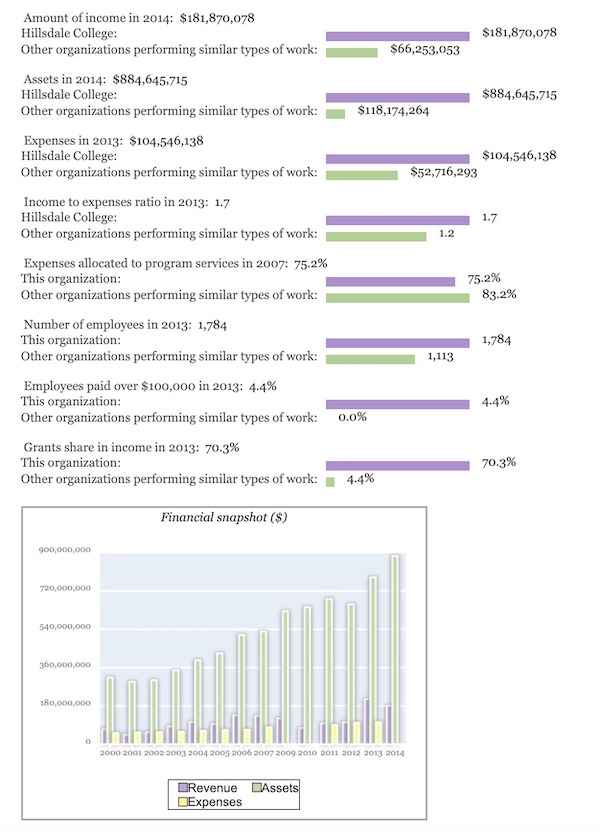

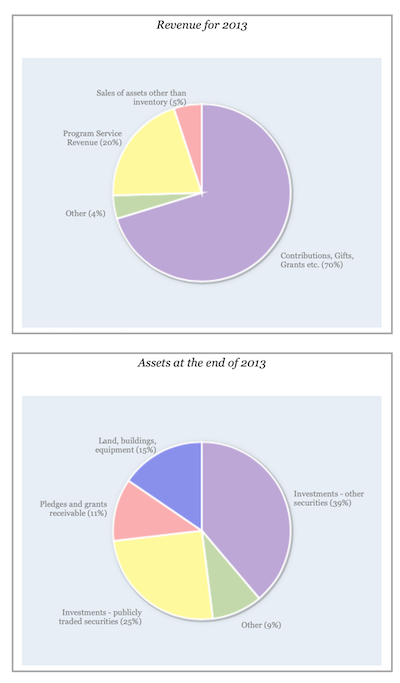

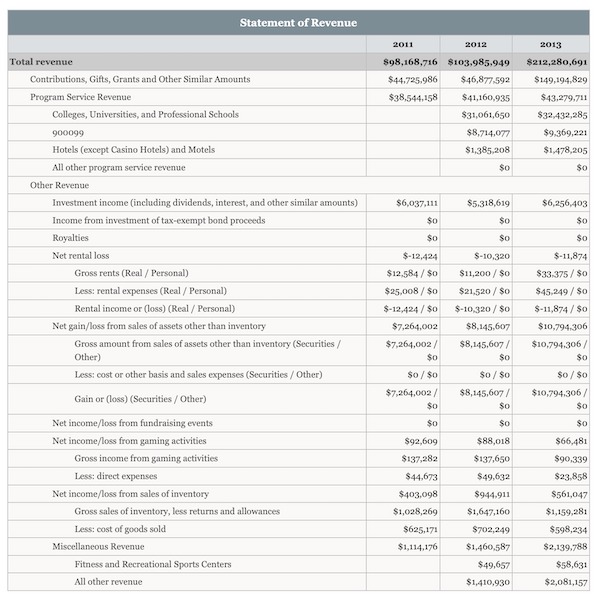

I was going to save it for later, but let’s look at Hillsdale’s financials to get an idea of what the institution looks like. As a nonprofit institution, Hillsdale is required to post its financials publicly. You can look at them here.

This data is from 2013, admittedly some time ago. The endowment has grown considerably. Hooray! If you are going to give money to a university, please support an institution like Hillsdale instead of the hundreds of other Cultural Marxist indoctrination centers.

The college apparently has 1,486 undergraduates, no graduate students, 124 full-time and 48 adjunct academic staff. (We will assume that this has not changed much since 2013.) The endowment in 2016 was listed at: $528 million.

On the revenue side, it is worth noting that Hillsdale does not receive any money from the Federal government, in the form of loans or grants. This was the result of some lawsuits in the 1970s:

Hillsdale’s modern rise to prominence occurred in the 1970s. On the pretext that some of its students were receiving federal loans, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare attempted to interfere with the College’s internal affairs, including a demand that Hillsdale begin counting its students by race. Hillsdale’s trustees responded with two toughly worded resolutions: One, the College would continue its policy of non-discrimination. Two, “with the help of God,” it would “resist, by all legal means, any encroachments on its independence.”

Following almost a decade of litigation, the U.S. Supreme Court decided against Hillsdale in 1984. By this time, the College had announced that rather than complying with unconstitutional federal regulation, it would instruct its students that they could no longer bring federal taxpayer money to Hillsdale. Instead, the College would replace that aid with private contributions.

This probably accounts, in large part, for Hillsdale’s characteristic conservative/American approach. In 1960, probably most of the colleges in the U.S., including (the all-male) Harvard, Princeton and Yale, were not that much different than Hillsdale today. There is a nice lesson here for refusing government money. But, that is the main reason for accreditation; so (although Hillsdale is accredited), we find that, if we have come that far, it is not hard to throw out accreditation too.

April 19, 2020: Build Your Own College #6: No Accreditation

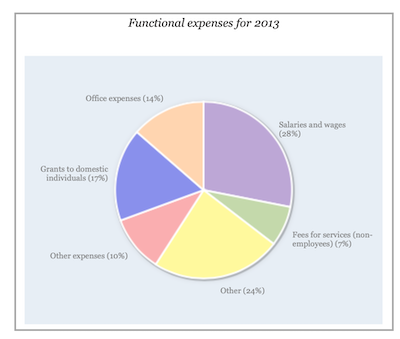

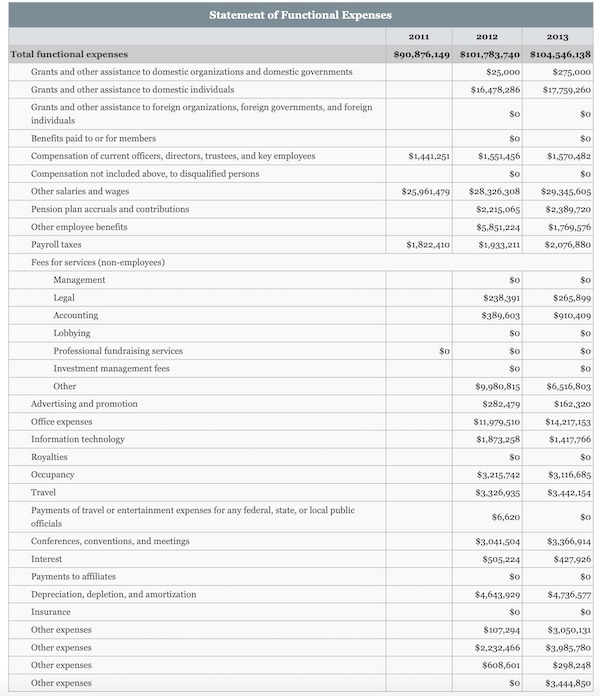

We see that in 2013, total expenditure was $104 million. However, this included $18m of grants (scholarships or financial aid), which is not expenditure on services itself, so the net expenditure was $86m. Among 1,486 students, that is: $57,873 per student. This includes room and board, so if we subtract $12,000 per student per year for that, the net is about $46,000 per student per year. The student/teacher ratio among the full-time professors was 12:1. There are a number of adjunct professors, which are abused and exploited low-cost labor in many colleges. Here, however, I can imagine that there might be a number of people of merit who do a little part-time teaching at Hillsdale, in a beneficial sort of way, so we will just pass over that.

The total costs of employees (salaries, payroll taxes, benefits) are $35,581,781, of which $29,345,605 (82%) are salary. Compensation for officers, of $1,570,000, is not too high in this oft-abused category. The salary for an assistant professor at Hillsdale is estimated at around $85,000 — a little above average, I would say, but a reasonable figure. Full professors and associate professors are likely over/under this figure, so it probably represents a good average. That translates into total employment costs of about $106,000 per full-time professor. From this, we can estimate that the employment costs of the full-time faculty are 124 X $106,000 or $12,896,000. In other words, only about 36% of the total employee costs are going to pay the faculty. The rest is absorbed by non-teaching employees. While there is some need for maintenance and minimal administration, it appears that the administration at Hillsdale is just as bloated as at similar institutions elsewhere. We looked at Colgate University, a similar sort of college, in the past:

June 19, 2016: Where Does The Money Go? Let’s Kick Around Colgate University

Hillsdale also has some other questionable expenses, including $6.5m of “fees for services,” and $14.2m of “office expenses.” (These “office expenses” cost more than the estimated total cost of the full-time faculty.) There is another $3.1m of “occupancy.” (Is this rent? Don’t they already own a campus?), and $3.4 million for travel. There is another $3.4m for “conferences, conventions and meetings,” which is a legitimate activity at Hillsdale, but I have to wonder why it costs so much considering that they already own a campus and have already paid the faculty, and already have a separate “travel” expense line for meetings elsewhere. There is $4.7m of DD&A (probably buildings), which is presumably offset by about the same amount of capex, which is not expensed. Nevertheless, this is a big number: are they caught up, like nearly all other colleges, in a process of continuous building expansion, like the Winchester Mansion? (“Space per student has in some cases tripled since the 1970s … Colleges have been prodigal.”) Then, there is about $10m of “other expenses,” which also seems high, but probably includes a wide range of student services and also catering costs.

Now, remember that we had about $86m of net expenses, and about $12.9m of total employee costs for the full-time faculty. If we just take 50% of the faculty cost for all non-teaching employees (including the officers) — this seems about as high as can be justified — that is $6.45m, for total employee costs (including officers) of about $19.4m, still only 22.6% of the $86m total. That works out to $13,600 per student. This doesn’t include something for room and board, which you can work out yourself. (The employee costs of building maintenance and catering are already included however.)

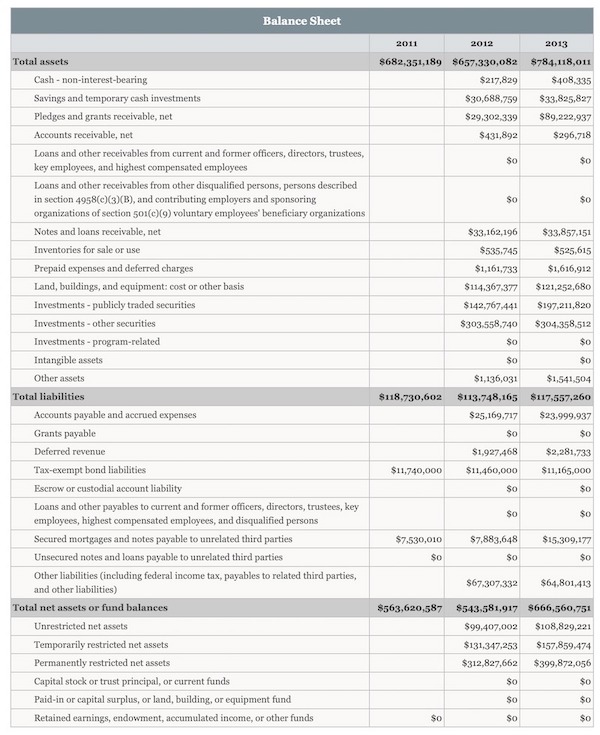

Hillsdale’s headline charges for room and board are: $5,900 for Room and $6,010 for Board, for a total of $11,910 per student per year, or $17,698,260 of revenue for these items. Since they own the dorms and dining halls, I assume that these are a net moneymaker; and that their real associated costs are less than this.

In other words, Hillsdale looks to me like a bloated mess, just like most other colleges today. You could cut the total expenditure in half and still have plenty to pay the faculty (at a cushy 12:1 student/teacher ratio), with plenty left over for buildings and grounds, catering, and even some conferences. Or, in other words, you could cut the spending per student from $58,000 to more like $20,000-25,000, including room and board — with the same campus, and the same faculty being paid the same amount, and the same student:teacher ratio.

Hillsdale had an endowment of $528m. Normally, an endowment is required to spend about 5% of assets on programs per year, which would be $26.4 million. That is $17,766 per student per “year” (which has thirty weeks of class). It does not count the amount of donated cash that goes directly into operating expenses and capex (new buildings), without passing through the endowment fund — which, in Hillsdale’s case, might be substantial. (They recorded about $45m of grant income in 2011 and 2012, and then a big $149m in 2013.) We just said that the total employee cost should be about $19.4m, including all administration and support staff, so the endowment could pay the entire employee expense, with $7.0m left over, which would come pretty close to covering all other expenses (including those related to room and board) if you were a little frugal about it. In other words, Hillsdale College could be completely free to all students.

Or, you could do something else with the money. For example, with about $10 million, you could establish a whole new college, perhaps beginning with buying an entire college campus like that of Green Mountain College in Vermont, for maybe as little as $3 million. Wouldn’t that be a nice use of the $26.4 million of annual (every year!) endowment revenue enjoyed by Hillsdale — rather than, for example, spending $14.2 million annually on “office expenses”? What if we scrimped and saved, and spent only $4.2 million per year on paperclips and copy paper, and used the $10 million left over to establish a whole new college in the Hillsdale model — every single year?

What if we paid off the $25m of debt on the balance sheet? (There is also $65m of “other liabilities,” which might include pension obligations.)

Since quite a lot of expenses and administrative overhead come about via compliance to accreditation requirements, an effort to reduce wasteful spending at Hillsdale might be accompanied by disposing of accreditation. Since Hillsdale already doesn’t accept government-linked money (the main benefit of accreditation), there is not much reason to go on with it.

I would not imitate the Hillsdale model as it exists today. For one thing, it is not so easy to get 1,400 students right out of the gate, so there needs to be a plan to grow from a smaller size, which probably also means a much narrower range of departments and majors. If you started with 50 students in the initial class, and four Teachers using Hillsdale’s 12:1 student/teacher ratio, in four years you would have 200 students; and then you can grow from there. That is a nice plan, and it is probably about how Hillsdale itself originally got started in 1844; although, probably with even fewer students and teachers than this. You can’t really establish a system of Departments and Specialists with four Teachers, so that might have to go too, in favor of the unified curriculum and generalist Teacher who is familiar with the whole curriculum; and so we come closer to the pre-1890 College model, which was exactly the model in which Hillsdale was founded, instead of the post-1890 University model.

Nevertheless, Hillsdale College still has many virtues and merits, and we should be glad that it has managed to maintain a high standard of education and enthusiastic support even in this dark and corrupt age.