Now that Javier Milei won an important election in Argentina, let’s see what his options are on fiscal policy. We looked at monetary policy earlier. I agree with Nicolas Cachanosky and Steve Hanke that full dollarization would be the best option for Argentina at this time. This would have a few complications, but it looks doable to me.

November 12, 2023: A Quick Look at Argentina

I don’t really know much about Argentina, but let’s take a look at some basic indicators.

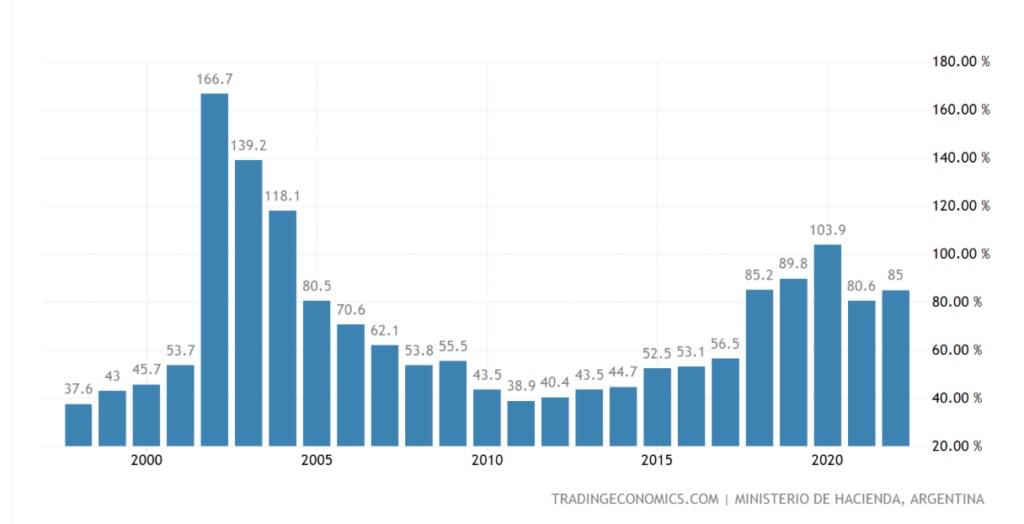

Government debt/GDP is pretty high. It has come down recently, mostly due to rising commodity prices (and thus GDP), and maybe, due to the devaluation of domestic currency debt. I assume the remaining debt is basically USD debt.

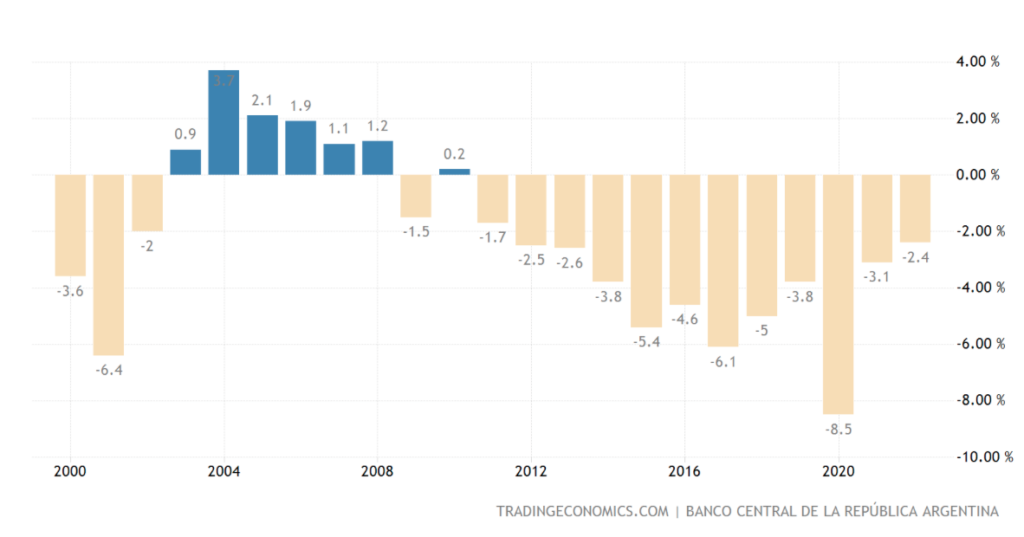

The government’s budget situation is not too bad. The problem is, they have been funding it with the printing press, since nobody wants to buy bonds from Argentina.

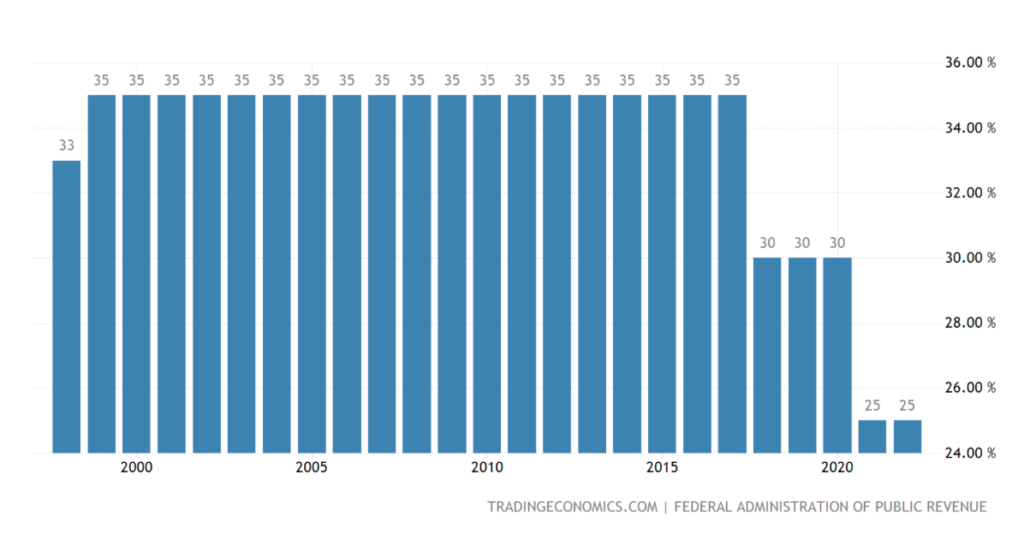

The corporate tax rate has come down, which I am sure has helped.

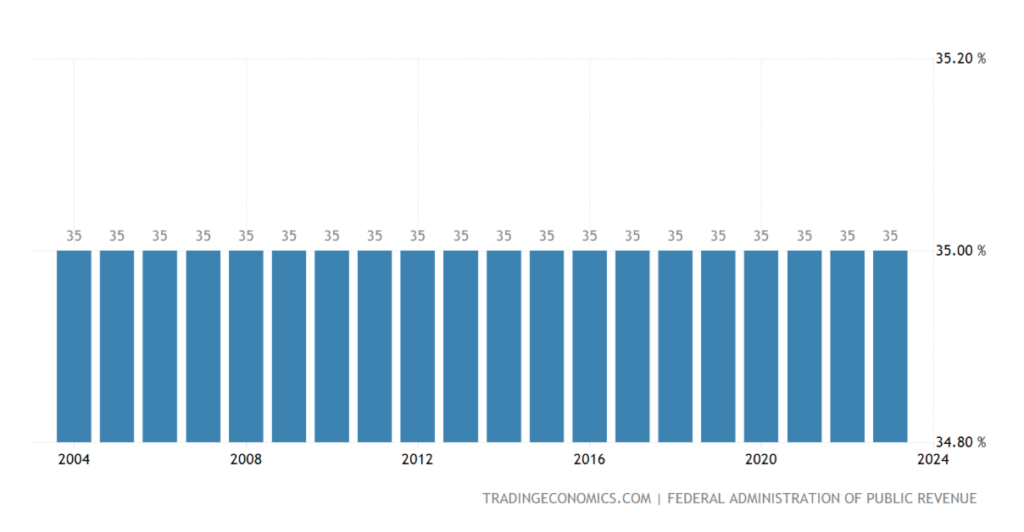

The personal income tax top rate is 35%, which is not too high by itself. The problem with countries with a lot of “inflation” is that middle class and lower middle class people get pushed into top brackets intended for the wealthy. But, Argentina has had so much currency depreciation over the years that I would imagine (I am obviously doing a lot of guessing here) that the income tax system is pretty well indexed to at least the CPI, ameliorating some of these issues.

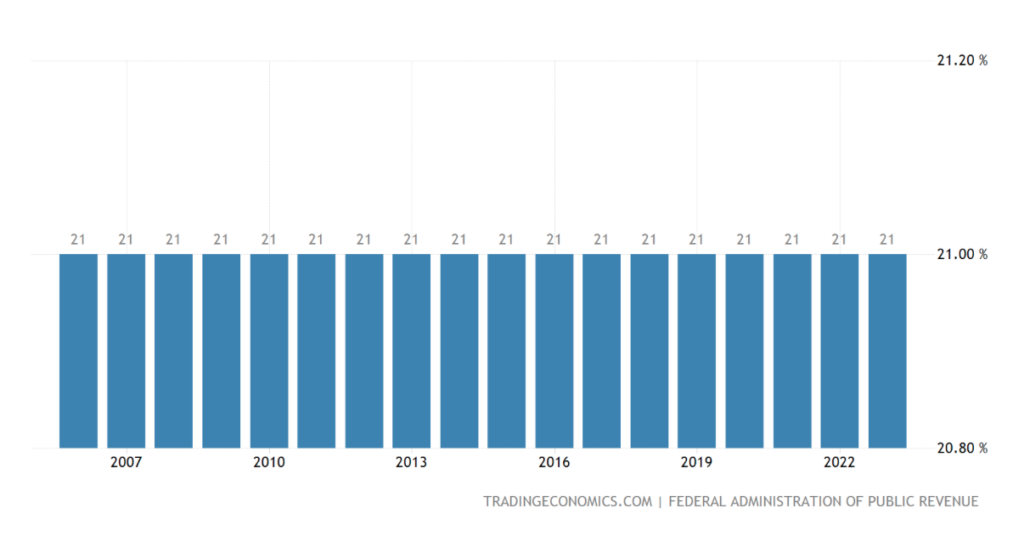

The “Sales Tax” or VAT is high at 21%.

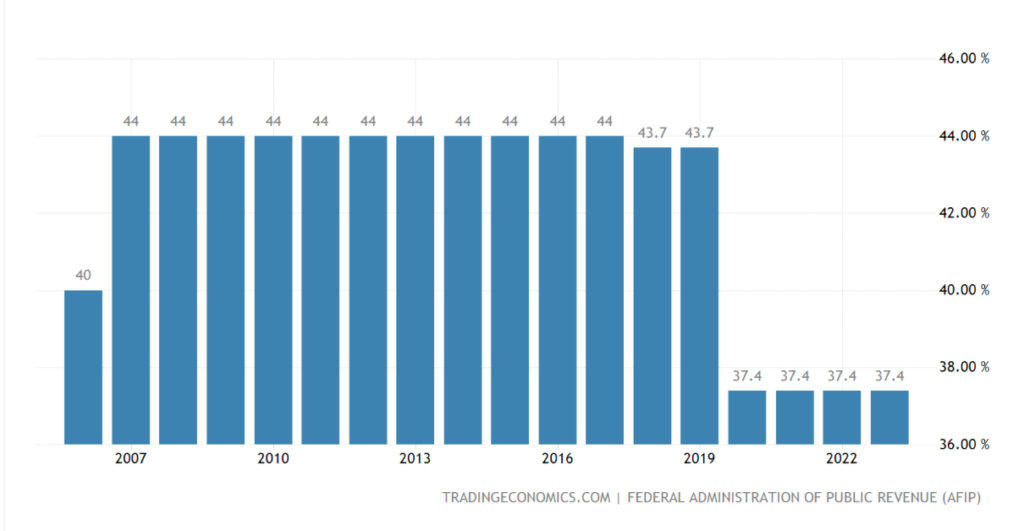

Payroll taxes are also very high, in the European socialist model. But, this has come down too.

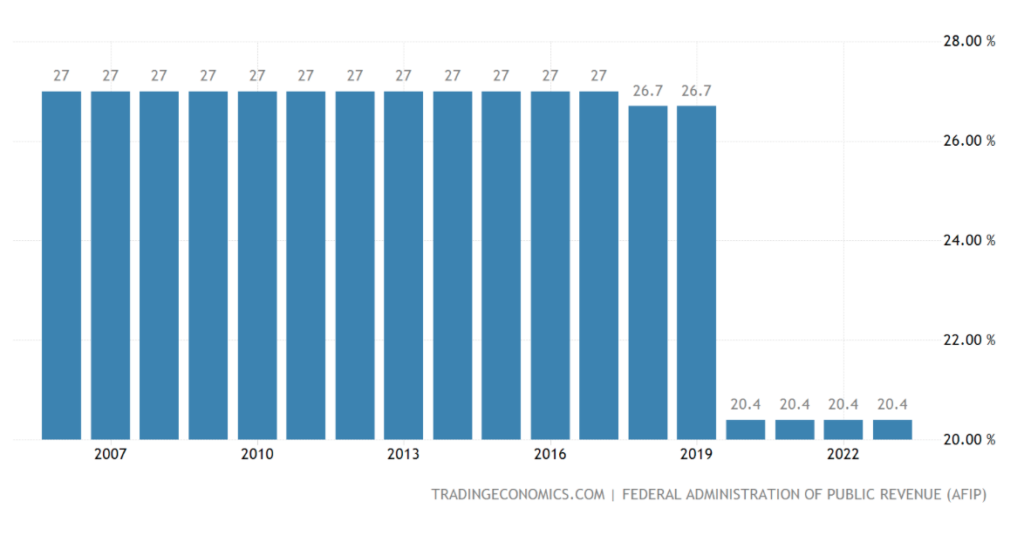

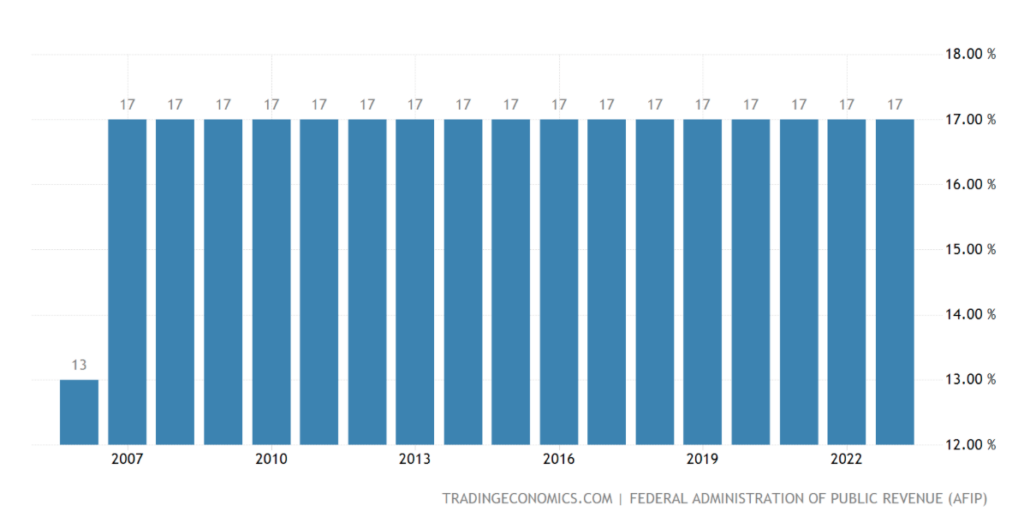

This payroll tax is split into a Corporate share of 20.4%, and an Individual share of 17%.

There are also some other goofy taxes, such as a 0.6% tax on bank transactions.

Wikipedia on the tax system in Argentina

Argentina tax system at PriceWaterhouseCoopers

All of this produces a tax revenue/GDP ratio of 30.3%, although this figure is from 2020, perhaps not a very good benchmark. This is a much lower figure than many European countries with a similar-looking tax system. This suggests highly to me that there is a lot of tax evasion in Argentina. At this point, people always say that “you have to crack down” (always the same stupid words) “on tax evasion, collect more taxes, and fix the budget deficit.” This never works.

Rather, I would say that the Argentine people are telling you what’s what: They simply will not pay more. The solution is to design a tax system that generates this amount of revenue, from much lower taxes which people are willing to pay.

Payroll taxes are, obviously, very high here. This is in the European model, where these high payroll taxes pay for social services, mostly healthcare and public pensions. But, it is a very high figure even for this. Probably, you could lower this tax rate and suffer no decline in revenue, even on a revenue/GDP basis. We saw that happen in Bulgaria, where payroll taxes were reduced in 2009 from 43.6% to 31.7%. The result was that payroll tax revenue/GDP was 7.71% in 2007, and 7.9% in 2016. Basically, tax evasion went down, while real employment went up. I would experiment with bringing these very high payroll tax rates down, and see what the result is. Revenue/GDP might not change, or might not change very much. If revenue/GDP was 7% at the present 37.4% combined rate, and 6% at a 15% combined rate, that is a lower revenue/GDP figure but all out of proportion to the decline in tax rates. But, against that, you would have a much stronger economy and a lot less tax evasion. The outcome would be more GDP, and thus more revenue, since 6% of a big GDP is more than 7% of a small GDP. (The US Federal payroll tax, at 15.3% combined, produces about 6.0% of GDP in revenue.)

Plus, with a stronger economy, you would have a lot more prosperity, which makes reducing other spending easier. As I argue in The Magic Formula, if you want to cut spending, cut taxes. Spending is a lot easier to cut when the economy is improving, people are self-sufficient, and are not clamoring for goodies or jobs from the government. This is, of course, the exact opposite of the “austerity” approach, where higher taxes “to fix the budget deficit” results in a weak economy, lower GDP, less tax revenue, more spending, and a bigger budget deficit.

Payroll taxes are typically “earmarked” for certain social spending programs, just like Social Security in the US. This leaves income taxes, and sales taxes (VAT).

Although the VAT is typically considered a variant of a Retail Sales Tax, actually, you can look at it as a type of Income Tax. Basically, “Flat Tax” proposals from the 1980s and 1990s were very similar to a VAT — as proponents of the plan argued at the time.

April 18, 2021: Grand Unified Theory of Indirect Taxes

If you think of a 21% VAT as the same as a 21% Flat income tax, from the first dollar to the last, then I think we can see that 21% is plenty for any government, especially on top of very high payroll tax rates to pay for all the Socialist goodies.

What I am arguing toward here is, getting rid of income taxes altogether, and keeping the VAT, which is actually a very good tax, just not when combined with a progressive income tax.

This would be a big move, so it could be phased in over time. For example, you can just take 5% off both corporate and personal income tax rates until they are gone. Since the top personal income tax rate is 35%, this would take seven years.

In The Growth Experiment Revisited (2013), Bush advisor Lawrence Lindsey recommended that the entire Federal tax system, both payroll and income taxes together, could be replaced with a 20% VAT. So, you see that, without exemptions and tax evasion, a 21% VAT can generate A LOT of revenue. (Value-Added is about the same as GDP, so you would expect a comprehensive 20% VAT tax to generate close to 20% of GDP in revenue.)

This would leave us with a 21% VAT and (let’s say) a 20% payroll tax, which is actually a pretty high tax system just there.

We looked at France earlier, and found that we could get about 35%/GDP in tax revenue just from indirect taxes alone — payroll and VAT — and no income taxes.

May 28, 2020: Let’s Ask Money Santa For A Better Tax System

I think Argentina would get about 25%-30% of GDP in revenue from a 20% payroll tax and a 21% VAT — with a lot less tax evasion. Also, the economy would be very strong, which would mean more tax revenue, and also, cutting spending would be a lot easier.

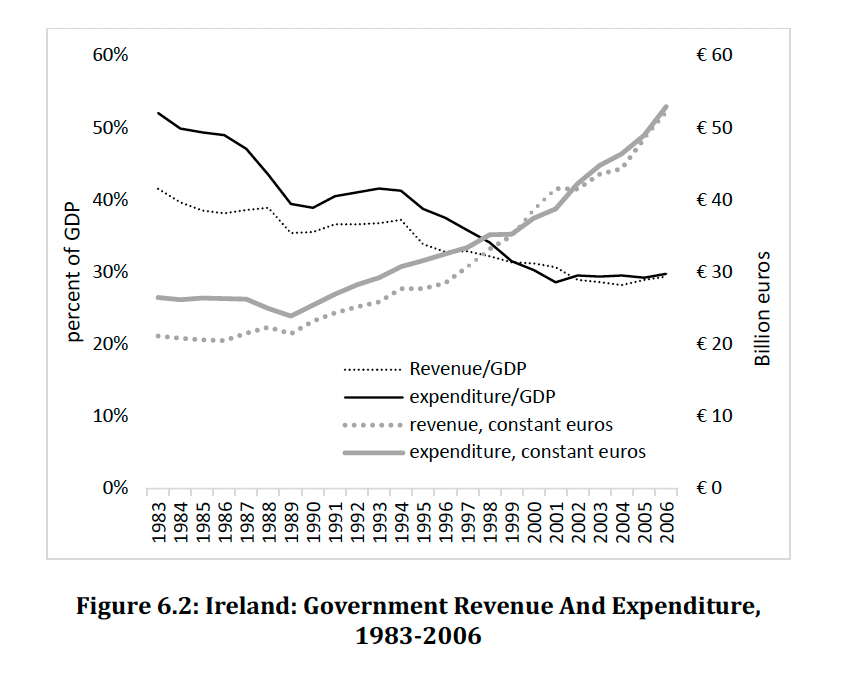

We saw in Ireland that big tax reductions produced a strong GDP, and consequently, a lot more revenue, and thus, a lot more spending! This took place even as revenue/GDP and spending/GDP ratios declined a lot.

So far, we’ve hardly done anything to modify the spending side. In the longer term, I would recommend moving from a mid-20th-century European Socialist framework, more toward a Singapore-style framework. Basically, this would mean replacing huge payroll taxes, and State medical care and Pensions, with a Provident Fund system like Singapore. A Provident Fund is mandatory contributions to earmarked savings accounts, similar to the Health Savings Accounts in the US, or 401k contributions. This is backstopped by various government programs for those for whom these provident fund contributions do not cover their healthcare and pension needs. However, the majority of people get by fine. Basically, this would mean that you would replace the 20% payroll tax (in our model) with, let’s say, a 20% mandatory contribution to a Provident Fund system. This works extremely well, which we looked at here:

Although the Singaporean healthcare system has effective Universal Coverage, and financial assistance for those with a low income, the total spending on healthcare by the government of Singapore on all these “backstops” is only 1.5% of GDP.

In these kinds of “crisis” situations, there is a question of timeframe. If big tax reductions — the system I am presenting here — is good, then isn’t it good right now, not phased in slowly? When Russia introduced its revolutionary 13% Flat Tax in 2001, tax revenues rose 41% in the first year of the new tax system. Eliminating the income tax system altogether, in Argentina, would be even more radical, of course. But, income from other taxes (especially the VAT) would rise, a lot. Since deficits are already an issue, and Argentina doesn’t really have any good way to finance these (relying on money creation), naturally there is hesitancy to do something that seems like it might lead to a big decline in tax revenue.

In the past, governments just said: “We will simply not issue any bonds. We are on a cashflow-only system. We don’t spend money unless we receive it first, in tax revenue.”

This is how Germany and Japan dealt with hyperinflation in the late 1940s. They also had huge tax reductions. Napoleon did something similar, after he came to power in France in 1799, also in the debris of prior hyperinflation. (I talk about Germany and Japan in The Magic Formula, and also, particularly for Japan, in Gold: The Once and Future Money.)

In other words, I would not dilly dally. If the full elimination of Income Taxes seems like too much at once, then go with a 10% Flat Tax in the first year. Then, phase out the Flat Tax, perhaps reducing the rate by 2% each year, or eliminating it in five years. Cut payroll taxes immediately. I would cut them to 30% in the first year, and then 25% and 20% in subsequent years. In the longer term, aim to eliminate Payroll Taxes altogether, replacing with a Provident Fund system. This would leave the 21% VAT as basically the only tax in Argentina, which seems about right to me for now. In time, I would reduce this too to about 10%, but that can be left to future decades.