“The ideal college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log, and a student on the other.”

— President James Garfield

When people imagine “founding a new college,” they probably imagine something that would cost hundreds of millions of dollars. You would have to get a whole new campus. You would need dozens of professors, and administrators. You would need hundreds, perhaps over a thousand, students. It seems daunting.

I propose a different approach. We have seen that our “college” can consist of one man — a very special man — and a bookshelf. The expenses of the college are, basically, the living expenses of this special person, plus something for facilities; and you could use his living room, to begin with.

This is not a college. This is a collection of buildings. Its purpose is to keep the rain off our heads.

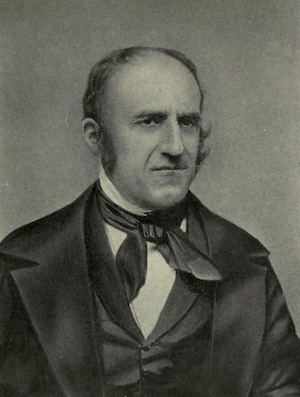

This is a college. Mark Hopkins, president of Williams College, 1840s.

Let’s say that you are an upper-middle-class parent, with three children spaced two years apart, who makes enough money that you can expect to, and are prepared to, pay full price for a private university education — about $50,000 per year per student. You are looking at around $600,000 of total spending, for your three children for four years each, for tuition alone.

You could instead go find this Special Man, and ask him to educate your children. You say: I will pay you $100,000 per year, for six years. It should cover your living expenses. You can go and find up to ten other students, to create your new college. In time, you can find more students, and add more teachers. In six years, you should be able to at least support a continuing institution for one teacher, and maybe, by that time, have several teachers. And off you go.

You just founded a college. And, it is exactly the way you want it.

It is best to start small. One Special Man. Or, perhaps two or three like-minded special people. At first, there will be a lot of experimentation. We will have a vision of how we wish to proceed, but inevitably, this vision will change as it comes up against realities. We hope it will evolve toward better outcomes. Or, perhaps it is merely a matter of practice. Even our Special Man needs some experience in how to best conduct a discussion group, or deal with students’ individual needs, or cultivate a “culture of discussion” among students. The Special Man becomes more familiar with the curriculum, through experience and practice. In short, there is a process by which vision becomes reality, and this process often has some refinement. A culture is formed; there is a precedent; a pattern emerges which can then be replicated.

The Special Man then finds another Special Person, who is themselves inculcated in this newly-invented process of education. The Special Man replicates himself. Now there are two. It becomes easier to bring in new people. Now there are four or five teachers, all of them basically interchangeable (no specialization) and all teaching the same curriculum. A similar thing happens among students. The first students build, from scratch, a pattern or culture of study and discussion. In time, they are third-year students, and teach this pattern to the incoming first-year students. The institution grows. But, we see that it is not very likely that we can just pile together fifty teachers and a five hundred students, right from the start, and get this kind of outcome. They would, inevitably, default to the patterns that they are already accustomed to, the patterns of existing “universities.” So, starting small is not only nice because it requires only one man and a little bit of money, but because, since we are largely creating things afresh, this is the only way you can start.

How much should this college cost? The answer basically lies in the student/teacher ratio. If we have 10 students per teacher, and we charged each student $20,000 for tuition, the total revenue would be $200,000. After paying a salary (let’s say it is $100,000) and benefits ($30,000), we would have something left over for necessary administration, and facilities. If we had 20 students per teacher, we could charge $10,000 each. $100,000 per year is pretty good for an academic, especially considering that they work only 30 weeks a year. It is enough to attract excellent talent.

The choice of the student/teacher ratio is a matter of some deliberation. More students is cheaper; and appeals to those who want to keep the costs of education low. Fewer students means more personal attention; and appeals to those who want to keep the standards of education high. For a long time, the better liberal arts colleges (for example Williams in Massachusetts) have had a student/teacher ratio of about 10-12:1. My personal preferences are for quality over price; and so, henceforth, I will look at the 10-12 students per teacher model. But, you could make an argument the other way, and it would be valid too. Anyway, $20,000 per year is pretty cheap these days. If you had 12 students at $15,000 per year, it would mean $180,000 of revenue per teacher, which is certainly doable. This is without any endowment or other financial support.

As the institution gets bigger, there will be a need for specialized administration. The process of admissions, and finding new students, is itself rather complicated. Eventually, buildings and grounds will need specialized staff. In time, a ratio of about one non-teaching staff for every five teachers may arise. Budgets will have to reflect this. In the early days, a single Special Man, or a few, may spread these responsibilities among their other duties. Or, a Founder (financial backer) may conclude that, to make sure that the institution expands successfully, there should be a non-teaching specialist whose responsibility is largely to find new students of high quality, to expand the student body. Thus, we may begin with Two Special People — a Special Teacher and a Special Administrator. But, the administrator (and later, administrators) should all be subordinate to the Teacher (and Teachers). The Teachers hire them, not the other way around. This is solved by the practice of students paying their Teachers directly, which is how it was done in the past.

When people think about “founding a new college,” they usually think of a campus — a bunch of buildings. Then, they fill these empty boxes with teachers and students. I say that a new college begins with a vision of education. This vision becomes reality among a small group of people — one to three teachers, and ten to fifty students. Or even just one teacher, and one student. This new pattern is then replicated, and grows. They use whatever buildings are at hand, and are appropriate for their needs. At one point in its early history, Johns Hopkins University, in Maryland, took place in some empty warehouse space above a storefront. The teachers and students were unified by a shared dream. But, the physical setting can be part of that dream. One person may dream of a college in a major metropolis, like New York City. Another imagines something in the woods of Vermont, or in Hawaii. I sometimes daydream of a “college” that took place while hiking the Appalachian Trail. We would hike in the morning, have lunch, read in the afternoons (via a portable Kindle reader), and discuss over a campfire in the evening. In the environment of the natural world, with no distractions or outside influences, great things could be accomplished.

Maybe this is a college?