Tokyo is one of the most expensive cities on earth; and also, a place where one can live cheaply, and well. Here’s why:

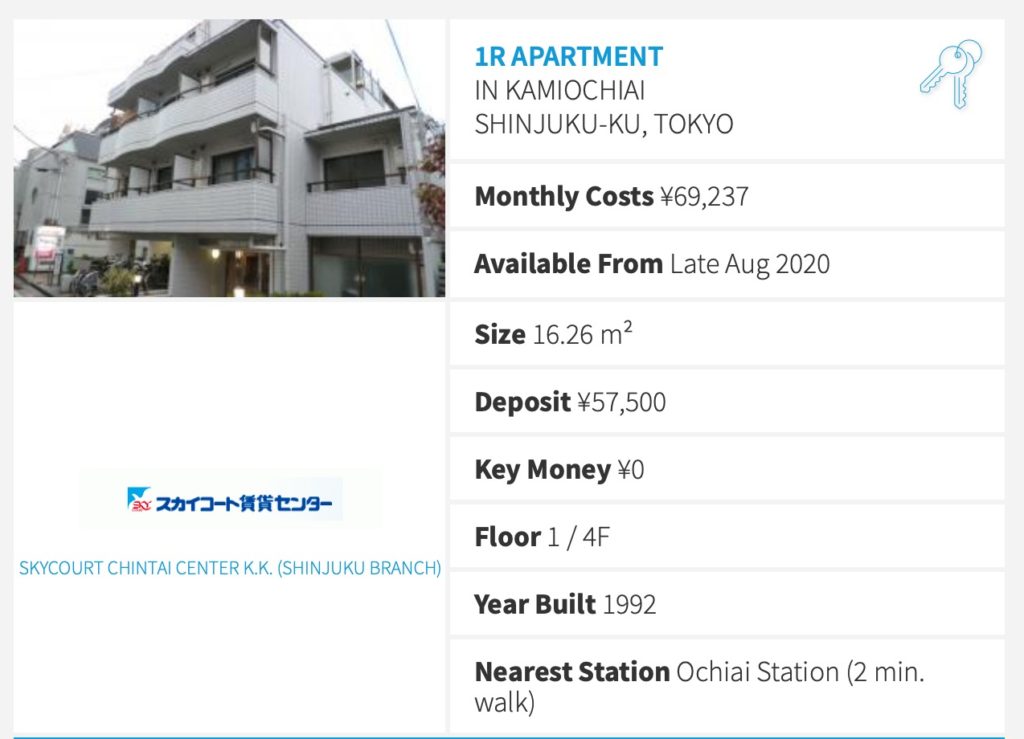

Abundant low-cost market-rate housing. Tokyo just keeps building, mostly replacing dingy old buildings with nicer, larger new buildings. The result is that there is more and more housing that is close to transit and the city center, even though Japan’s overall population is shrinking. You can spend as much on an apartment as you want, but you can also spend relatively little, for example about $700 a month for a 200sf studio in the central area. You get what you pay for — this is market rate — but you don’t have to spend much if you don’t want to. Here is one example: a 16.26m3 studio in central Shinjuku-ku, in a nice modern building, with a balcony, a two-minute walk from the train station, for 69,237 yen (about $630) per month. Young people wishing to minimize expenses will often split an apartment like this, bringing their housing costs to about $400/month including utilities. Tokyo apartments tend to be very small, not because you can’t get a larger place if you want, but because people would rather spend their money on other things.

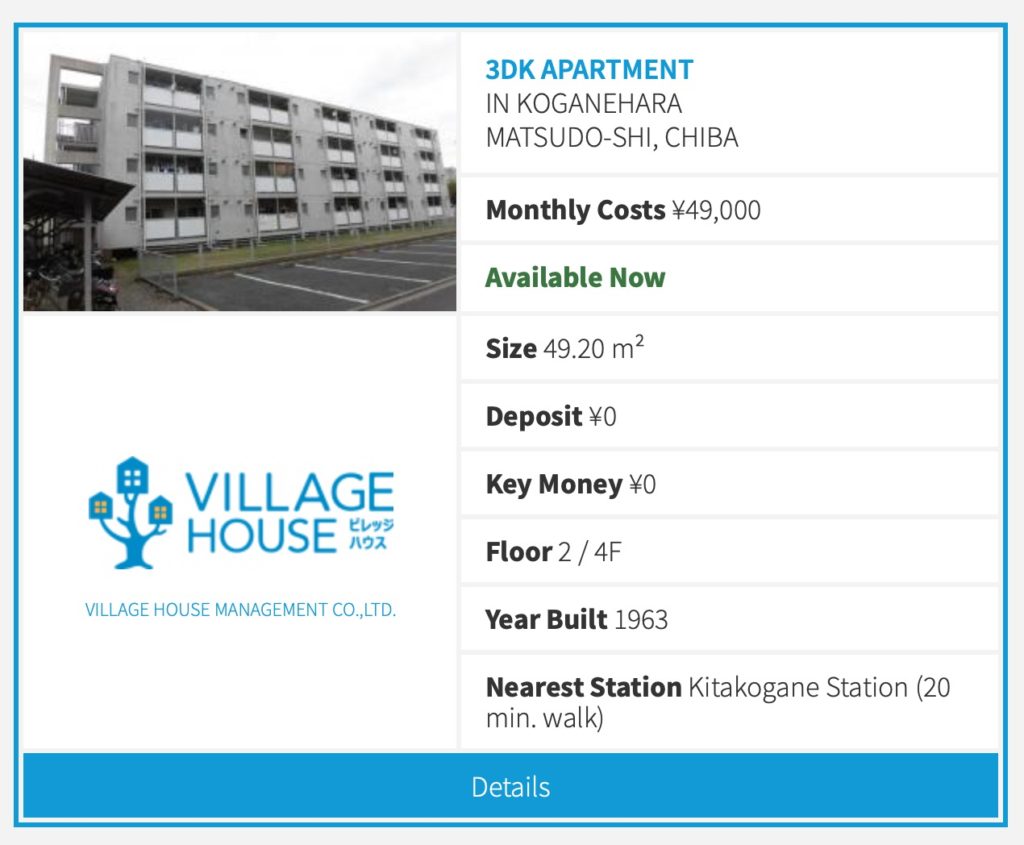

If you go out into the suburbs, it gets a lot cheaper. Here is a two-bedroom apartment that is walking distance (a long walk but a short bike ride) from the train station in the suburbs of Chiba. The rent is 49,000 yen, or about $450.

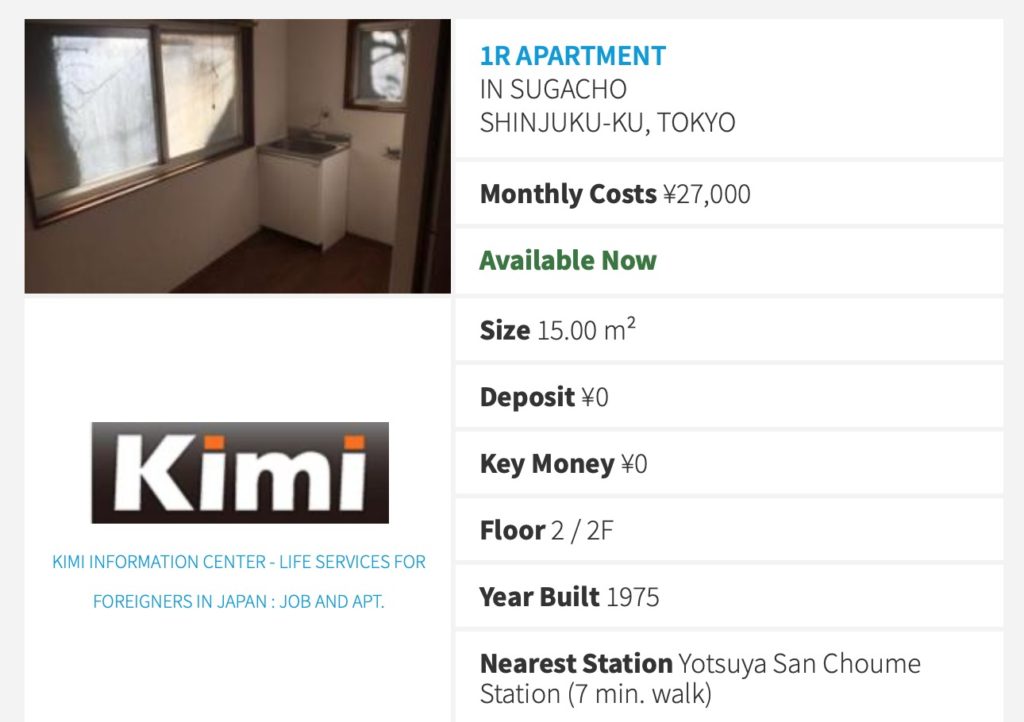

There are even cheaper apartments than this. Here again in the central Shinjuku district, is an apartment for $250 a month — full market rate. Again, you get what you pay for. There’s a reason most people pay 2x or 3x more. This apartment has a toilet but no shower or bath, for example (when it was built, the public bathhouse was probably common); the kitchen is just what you see and no more; the building is the kind of old, dingy thing that is being torn down for nice new modern apartments. When the lot is rebuilt, it will be done at six stories instead of two. But, if you only have $250, there’s a place for you too. And, it is a 7 minute walk from the train station.

Millions of cheap, market-rate apartments, with thousands available for rent on any day of the week. No rent controls and no “affordable housing” subsidies, inevitably available to only a lucky few. “Gentrification” and “displacement” are never an issue, because you can easily move to one of thousands of alternatives always available. Shinjuku Ward, where these apartments are, has a population of 337,556 in 7.04 square miles, or about 48,000 per square mile. If the City of San Francisco was built to a density of 48,000 per square mile, up from 18,000 today, more than twice as many people could live there.

This is what $620 gets you in Tokyo. A small apartment in a nice new building, in a nice neighborhood, in a central location, 6 minutes from a train station.

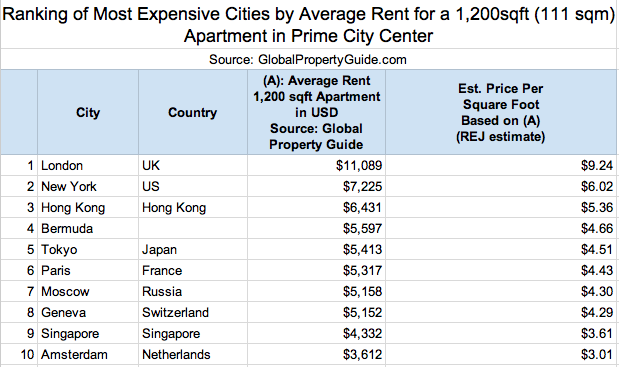

Despite all the new construction, Tokyo is still one of the most expensive cities in the world for apartment rentals, on a per-square-meter basis. But, you just don’t have to rent very many square meters. This data from 2015 is somewhat outdated, but gives the basic picture:

No Car necessary. With Tokyo’s superlative train system, you don’t need an automobile. Just a cheap monthly train pass.

No bad neighborhoods. There are more fashionable neighborhoods, and also working-class neighborhoods, but there are basically no bad (ugly, dirty, crime-ridden) neighborhoods in Tokyo. You could live in a comfortable and dignified (but modest) manner just about anywhere. Local “koban” police outposts are found in every neighborhood, keeping an eye on trouble. This is possible in part because of the high density, about 40,000 per square mile typical in central areas. A policeman has to patrol only a very small area.

Acceptable schools. Japanese public schools are rarely great, but also rarely awful. You don’t have to play the “neighborhood with good schools” game so common in the U.S.

Narrow Streets for People. The streets in residential areas are quiet (very little auto traffic), humane, pleasant and safe for children and the elderly. You aren’t struggling constantly with unpleasant urban environments. You don’t have to own a suburban yard as a way to compensate for a city that is intolerably ugly for raising a family.

Plenty of parks. From tiny neighborhood “pocket” parks to big destination parks, there are plenty of places for children to play and adults to relax, often very close to the house. You don’t need to have your own private yard as a refuge from urban unpleasantness

If you add it all up, you can see that you can live comfortably in Tokyo — even in one of the more fashionable neighborhoods — for as little as $1000 a month, a minimum-wage salary. On the other hand, you could also spend that much for dinner if you wanted to.

Unfortunately, in the U.S., we have created a situation where cities are either too expensive, or too ugly/unsafe/dismal/crime-ridden/unfit for families and children to endure. The result is that living is very expensive. You have to pay a lot either to get into those urban neighborhoods that are deemed acceptable to middle-class values, or you have to pay a lot to get into a suburban automobile-dependent detached-single-family suburb.

We should imagine that city living is cheap, clean, beautiful and fun. You don’t need a car. You don’t need a big house. You don’t need a big yard. What we find is that even those people that don’t have a lot of income — even a minimum-wage income — can live a decent and respectable middle-class life. They live modestly, but they are not struggling to get by.

Eventually, we can see that only dense city living can provide this. Only dense city living can allow living without an automobile comfortably, or very low housing costs in multifamily apartments instead of detached housing — all at market rate. You need a lot of density to make transit systems viable at low cost and a high number of trains or buses per hour. You need a lot of density to put parks within walking distance of residences, or to be able to walk to the public library, school and supermarket.

Many of our difficulties with lower income or even homeless people today won’t be solved by giving them more money, but by creating an environment where you don’t need much money to get by.