In the past, I did a review of various “interpretations” of the Great Depression. I did not spend very much time on “Austrian interpretations,” except to give some basic characteristics. It would be worthwhile to spend a lot more time on these, including the works of F. A. Hayek of that time, or Lionel Robbins. Basically, the Austrians got stuck in the “Price, Interest, Money” model of economics, popularized in the late 19th century by Leon Walras and Carl Menger. In the Austrians’ view, you wanted Stable Money so that prices and interest rates could be determined by the free market. This same basic model was turned on its head by Keynes, who, in the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) , argued that you could use the same principles to manipulate the economy, via the currency (its quantity or especially its value; basically, a currency devaluation) or via manipulation of interest rates, which would change capital allocation (lending), and thus create more Employment. So, when the Great Depression happened, the Austrians immediately assumed that the decline in Prices, and employment and economic contraction in general, had to do with some kind of harmful manipulation of Interest and Money. The Keynesians argued (correctly) that Interest (credit) and Money were basically fine, but the economic decline happened anyway due to “a decline in Aggregate Demand” (“there’s a recession!”). Although the Keynesians never really identified where this recession came from, they thought they could do something about it by manipulating Interest and Money.

October 2, 2016: The Interwar Period, 1914-1944

August 25, 2017: The Interwar Period #2: It’s Not That Complicated

Both the Austrians and Keynesians had the right idea, at least in part. The Keynesians were correct that the decline of 1929-1932 didn’t really have anything to do with preceding problems of Interest (credit) and Money. The Austrians were correct that governments, in the early 1930s, should not create new problems by messing with the Interest and Money, as Keynes suggested.

It is not very hard to find many, many problems of that time that were basically nonmonetary, beginning with a major tariff war worldwide that soon, via “austerity” arguments, led to dramatic increases in domestic taxes. This was accompanied by all kinds of socialistic and interventionist influences upon the economy, exemplified by Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which Amity Shlaes chronicled nicely in The Forgotten Man (2008)

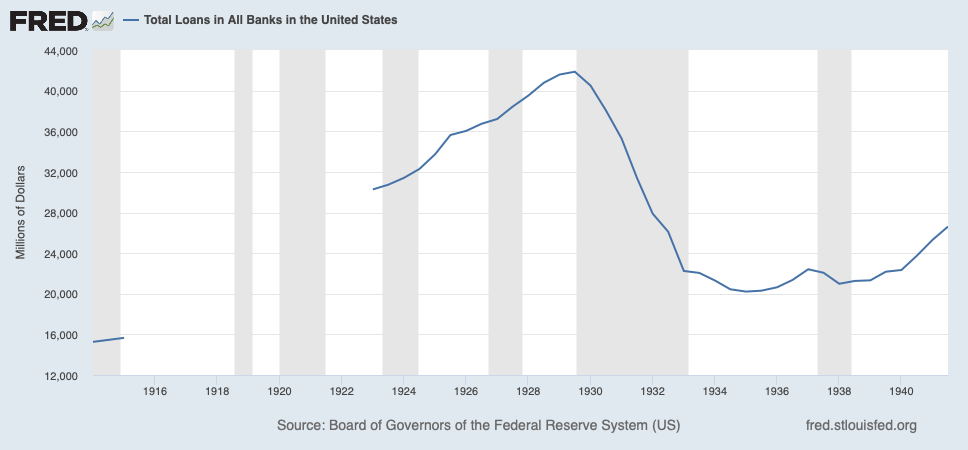

Nevertheless, there was certainly something important happening with Credit. There was a huge credit contraction in 1929-1932. This was called the “Debt Deflation” model by Irving Fischer, and is very similar to the credit cycle process explained recently by Ray Dalio.

To give an idea of what I mean by credit contraction, let’s say that all banks tomorrow demanded immediate repayment on all existing mortgage debt. Two things would happen: Some people would be able to pay this off. But, they would have to sell other assets to do so. Bank deposits would be drawn down. Stocks and bonds would be sold. This would drive a decline in stock and bond markets, and also cause distress at banks, which would have a dramatic decline in deposits. This decline in deposits might cause banks to contract credit more. Some people would have enough equity in their house that they could sell the house on the market, and pay off the mortgage while having something left over. But, this would cause a decline in house prices — first, because of all the forced sellers; and second, because potential buyers would probably not be able to get financing (a new mortgage loan), and would have to buy with all cash. Some people would not be able to make the payment at all, and wouldn’t be able to sell their house at a price to cover the payment. These mortgages would default. The bank would end up owning the house, which it would sell on the market, thus depressing house prices. The bank would probably take a loss here, which would lead to bank failures, which would lead to a further contraction of deposits because the failed banks’ deposits would be defaulted on.

It is important to see that this “credit contraction” model has nothing to do with the money. The dollars here are the same old unchanging dollars. It would all be exactly the same if everyone used gold coins, and there were no paper banknotes and no central banks. This Credit process is completely different than a Monetary process.

This thought exercise is not entirely fanciful. Mortgages in the 1920s tended to be for shorter terms. The common mortgage in the 1920s was a five-year balloon mortgage. Commonly, these were rolled over after five years into a new loan. However, in the credit crunch of the early 1930s, banks would not roll these mortgages, and demanded repayment of principal. The hypothetical process I just described became real life. By 1934, 25% of all home mortgages were in default. This is why the 30yr fixed-rate fully amortized mortgage was imposed by Federal Law, namely the National Housing Act of 1934. Amendments to the National Housing Act in 1938 created the government-sponsored lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

This credit contraction might come about from a number of causes. One potential cause is poor underwriting of prior lending. In the case of home loans, this would be banks lending to people who could not realistically pay the loan. This was a big deal in the 2005-2008 housing bust. On the corporate level, it would be debt-financed investment in new business expansion that did not make enough money to pay the debt.

I have not found much evidence that banks were overly aggressive in their lending in the 1920s. It is easy to just assume so, because many of these loans did go bad. But, I think that was mostly due to things that happened afterwards (the Tariff War among them), that made otherwise good investments go bad. I do not consider myself an expert on this topic, and I have never seen anywhere a good investigation of it.

April 3, 2016: Credit Expansion and Contraction of the 1920s and 1930s

May 14, 2016: Credit Expansion and Contraction of the 1920s and 1930s #2: Paying Off Debt

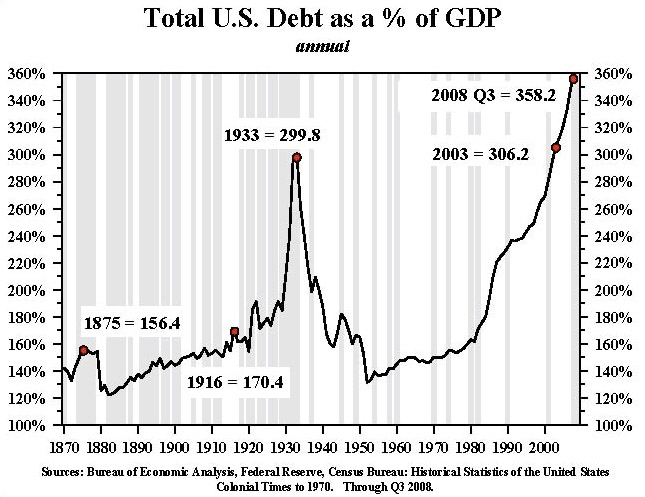

It is easy to look at this chart and say that there was a huge increase in debt in the 1920s. But, actually the increase in debt/GDP was due to the shrinkage of GDP, after 1929. The figure for 1929 was not very high. It was a little higher than the pre-1913 level, but not a lot higher, and that was accounted for entirely by the increase in government debt due to World War I (about 30% of GDP). In other words, private market debt was no higher in the 1920s than it was for the decades previous to 1913, which, as we can see, was not very high.

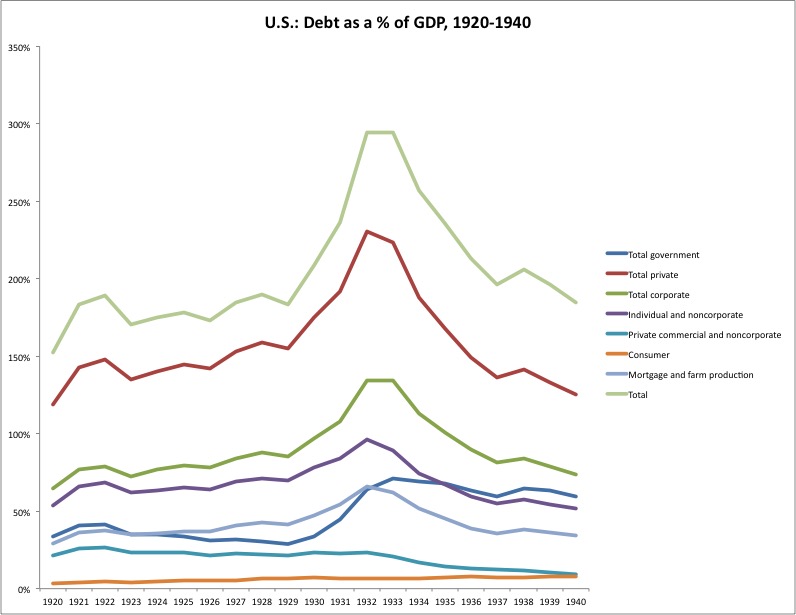

Here are debt/GDP levels for various subcategories of debt. Government debt/GDP was about 30% in the 1920s, from very low levels prior to 1913. All categories of private-market debt, and Total Private as a whole, did not rise very much during the 1920s. This was also the regular pattern prior to 1913, and also during the 1950s and 1960s. GDP and debt tended to expand in line together, so that debt/GDP did not grow much. This pattern changed dramatically after 1980.

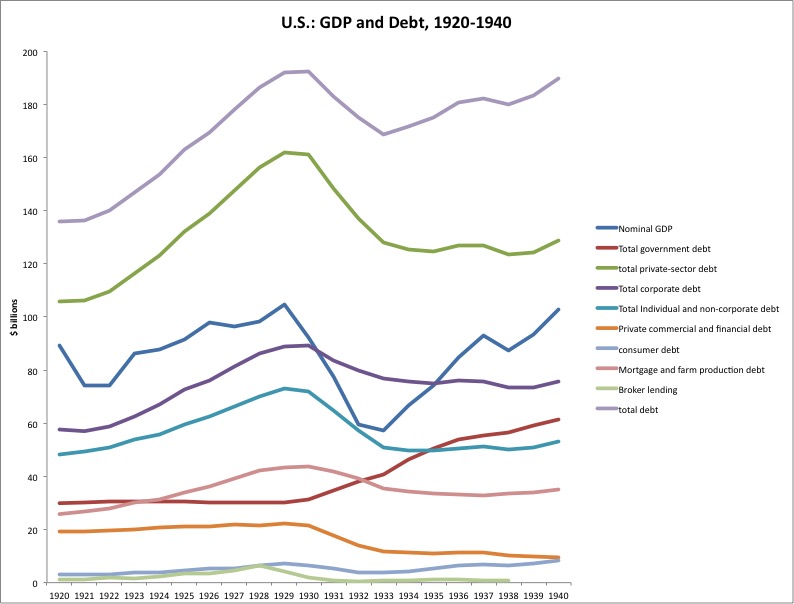

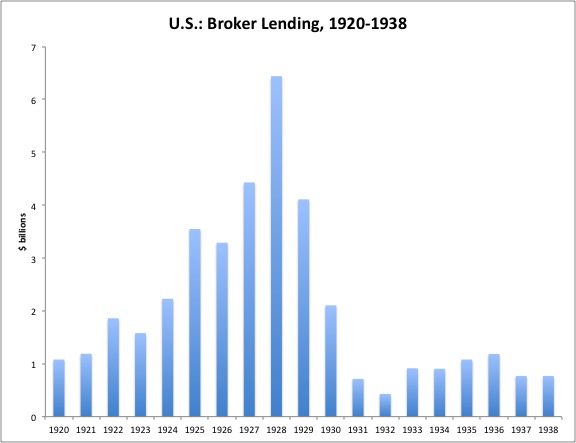

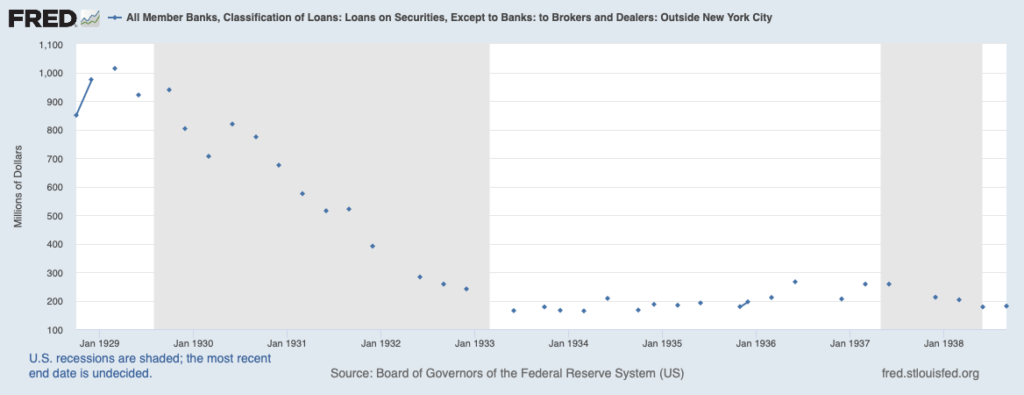

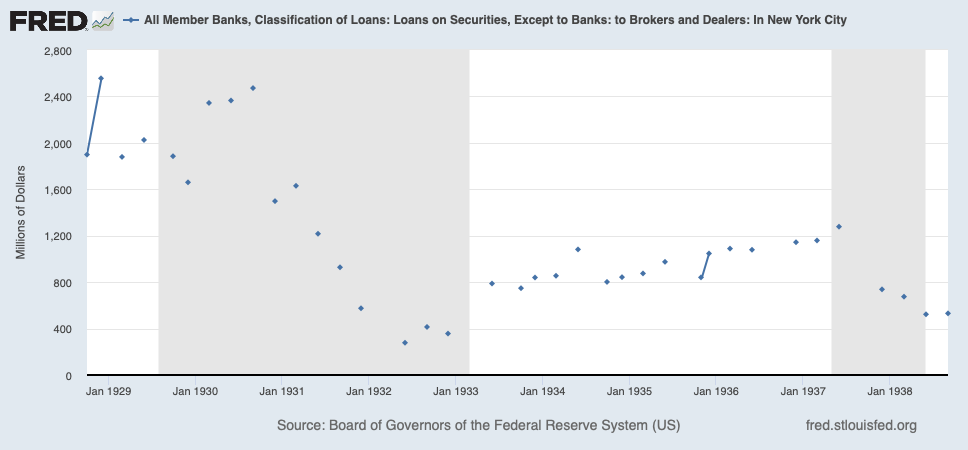

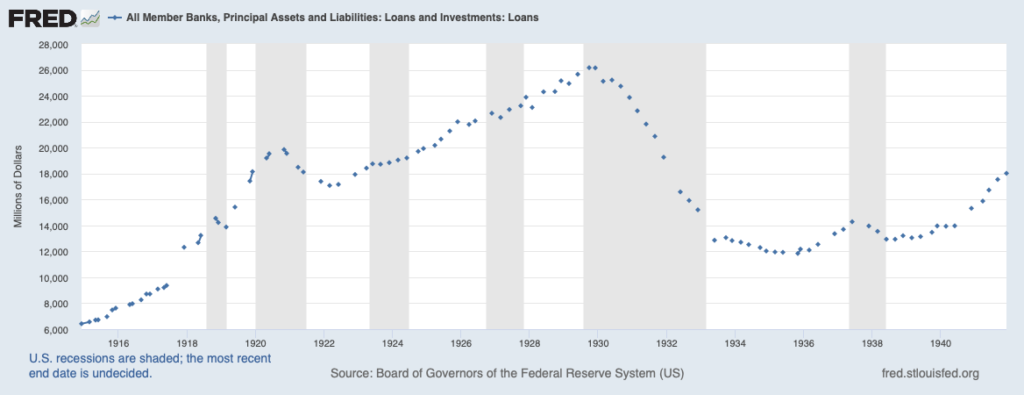

Here are debt levels in dollar amounts, not a percentage of GDP. We can see the expansion of debt in the 1920s, in line with GDP, and then the big contraction of debt levels in 1930-1934. This is the “credit contraction.” Broker lending was a small part of overall credit, but, in percentage terms, it had a huge increase and decline that followed the stock market.

It is interesting to note here that the peak in lending to brokers and dealers (which then became margin lending on securities) was in the first half of 1929.

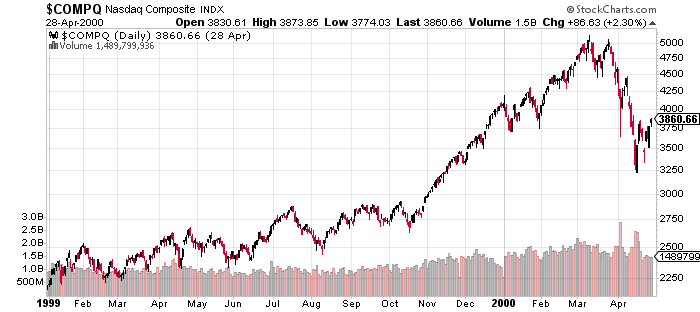

There wasn’t a parabolic rise in the stock market in 1929. Rather, the market was rather flat for the first half of the year, and then rose in the second half. Not really “bubbly” behavior.

For contrast, here is the Nasdaq in 1999. It nearly doubled in the space of a few months. Bubbly!

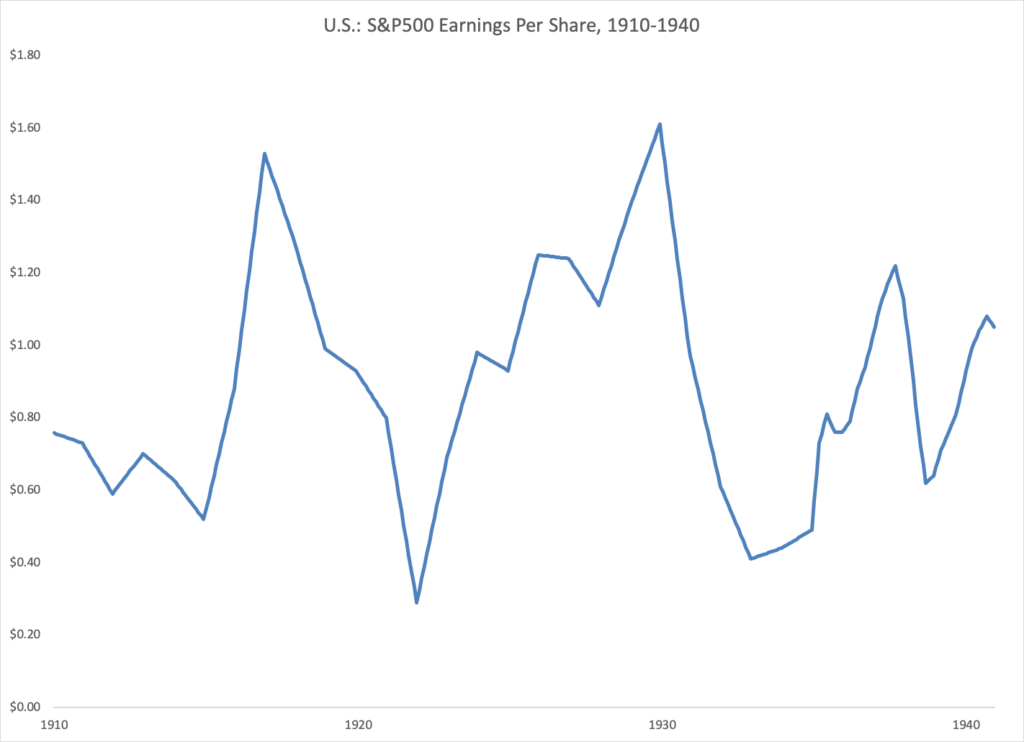

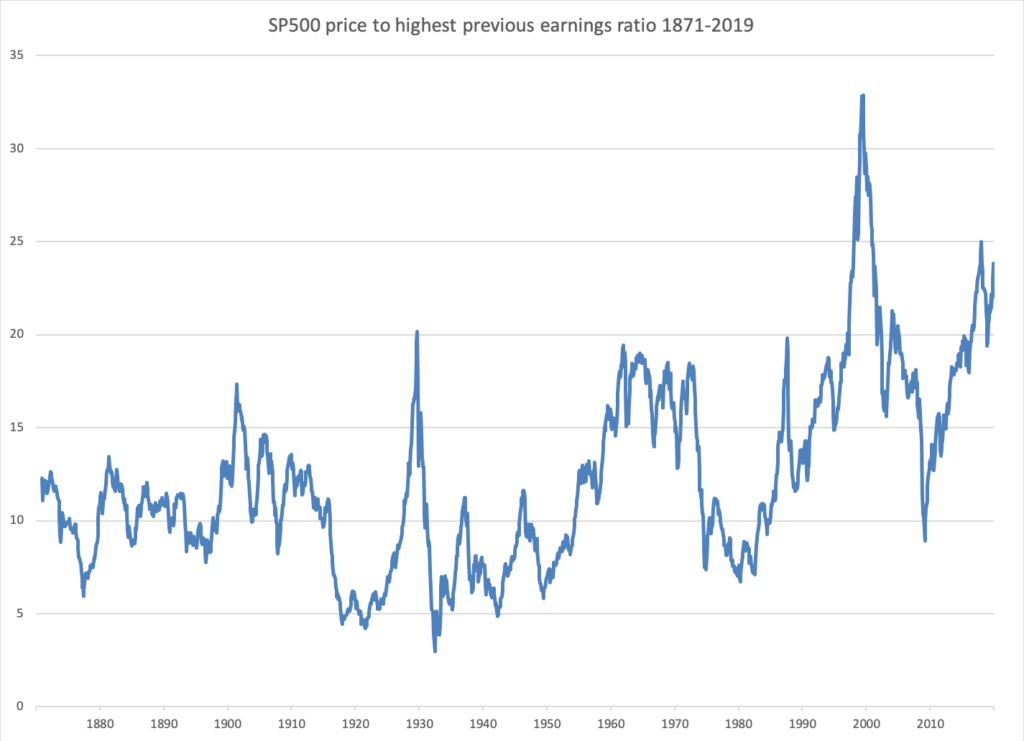

The stock market was not particularly overvalued in 1929. It traded at about 20x trailing reported earnings — a fairly modest figure, considering that earnings were growing at double-digit rates.

Here is a chart of the SP500 to the highest trailing earnings achieved. This eliminates high p/es due to declining earnings (recession).

The bull market of the 1920s was breathtaking, but entirely within reason given the extraordinary economic expansion of that time. Even with the crisis at the end of the year, actual reported earnings rose 17% in 1929, following a 24% rise in 1928. So, I do not think the expansion of margin debt created unjustified valuations of US equities.

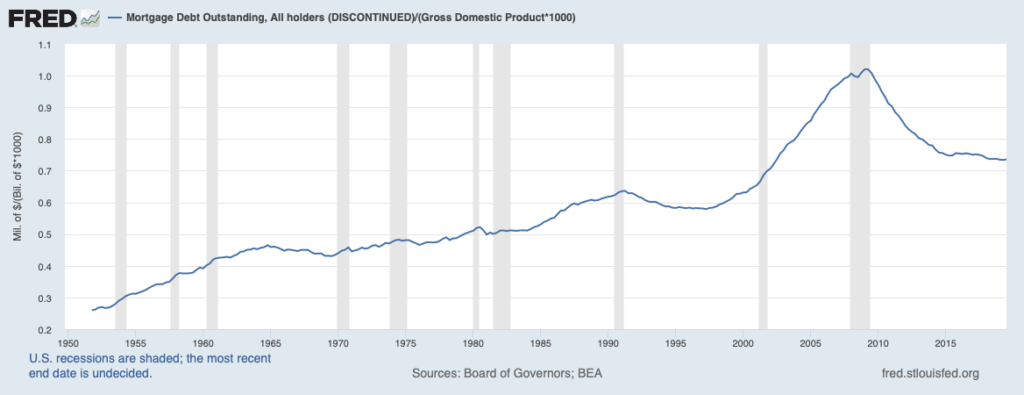

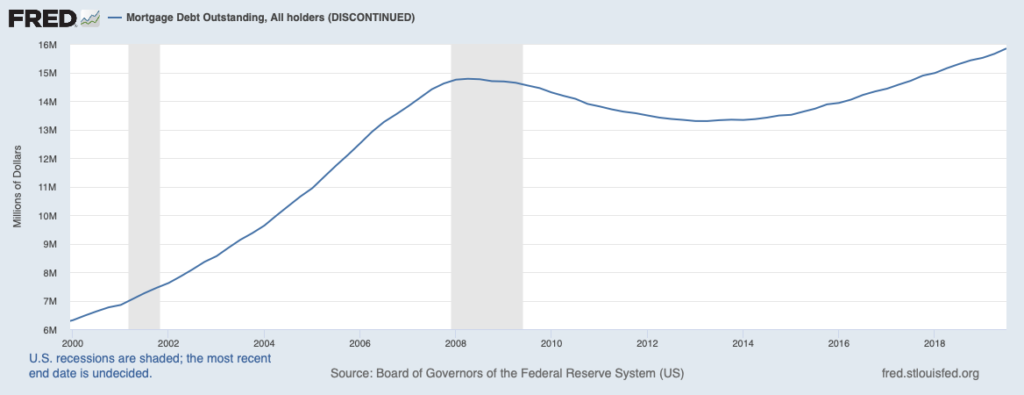

Except for a few small pockets like margin lending on stocks, I don’t find any particularly odd behavior of lending. There is nothing like the expansion of mortgage debt we saw during the “housing bubble” of 2002-2006.

Here is mortgage debt in the US vs. GDP. You can see the huge surge in this figure, compared to GDP, and then the big decline afterwards. This is a “credit bubble.” Nothing like this happened in the 1920s.

In nominal dollar terms, mortgage lending declined by about 10% in the credit bust of 2008-2012. Think about how traumatic that was. In the 1930s, total nonfinancial private-sector lending contracted by about 30%, and those were annual figures, not monthly. In the monthly figures (see below), the decline is greater than 50%. This is really incredible; and, for 90 years now, economists haven’t had much to say about it.

In the 1930s, there was a “bust,” but there was no “boom” in the 1920s. The expansion of bank lending in the 1920s was rather modest, and in line with expansion of GDP. (The sharp recession of 1921 pretty much cleared out any excessive lending from before 1921.)

Here is total lending at US banks (Federal Reserve member banks), from 1914. In 1914, the U.S. was not involved in the War in Europe, so this was a “pre-1914” state, you could say. We can see that bank lending increased by about 4x between 1914 and 1929, from $6,000 million to $24,000 million. But, GDP increased by almost 3x, from $36,831 million to $104,600 million.

Here is info on all US banks. It follows the pattern of Fed member banks pretty closely.

The Austrians got into a lot of confusion between credit and money. It seemed to them like bank deposits (a form of credit) were a form of money. So, the expansion of bank credit, on both the asset side (lending) and liabilities side (deposits) seemed like a “monetary expansion,” which could be inflationary (decline in currency value). This was complicated by the fact that commercial banks really did issue their own banknotes, in the pre-1913 era, and actually up through the 1930s. This confusion was typified by Ludwig von Mises’ Theory of Money and Credit (1913). Without going into the contents of that book too much, you can see the confusing intermingling of these concepts in the title alone.

Bank deposits can certainly serve as a substitute for cash (money), but it is not money itself. For one thing, you can’t transfer it. It doesn’t change hands. If you have a checking account at ABC Bank, and you buy something, the seller does not receive a checking account at ABC Bank. The checking account at ABC Bank does not change hands. What actually happens is this: Your bank, ABC Bank, pays the seller’s bank, XYZ Bank. This payment is done with bank reserves held at the central bank, such as the Federal Reserve. These bank reserves are a part of Base Money, the only kind of money that actually changes hands and can be used in payment.

Thus, your debit card from ABC Bank is a substitute for holding $100 of cash, with which to pay the seller. But, it is not the same as $100 of cash. It is not money. We do not have any trouble seeing this distinction when it comes to credit cards. Nobody would consider a credit card with a $5000 credit line as a form of “money.” But, if we consider the mechanism of credit cards; namely, that the bank pays the payee’s bank, and then adjusts the amount of money it owes you/you owe them, we see that there really isn’t much difference between the two.

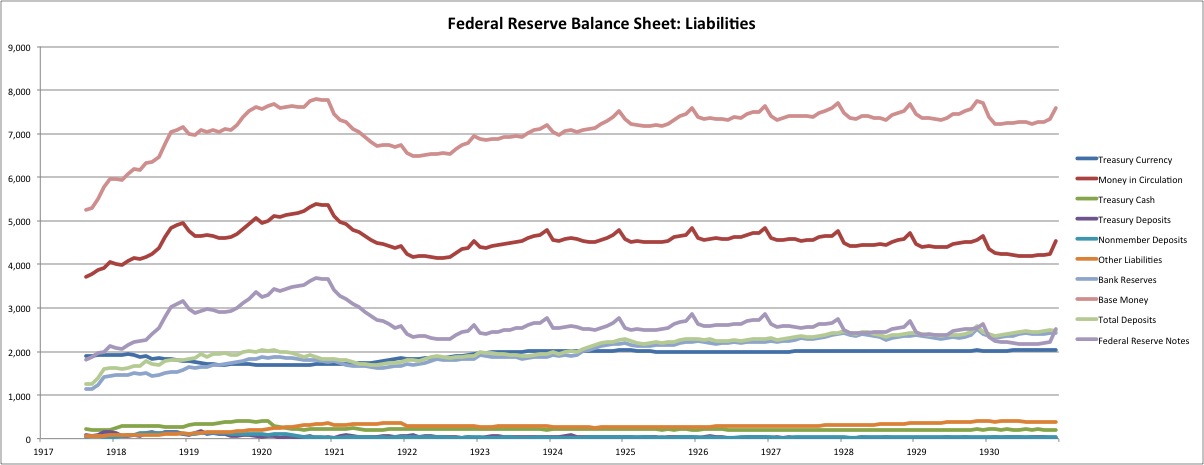

So, the Austrians tended to see credit expansion and contraction (basically, the process described by Ray Dalio) as a monetary expansion and contraction, which would lead to a rise/decline in the value of the currency. But, this did not happen. Currencies in the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s were linked to gold. They were on the gold standard, and central banks operated these gold standards more-or-less as they were supposed to.

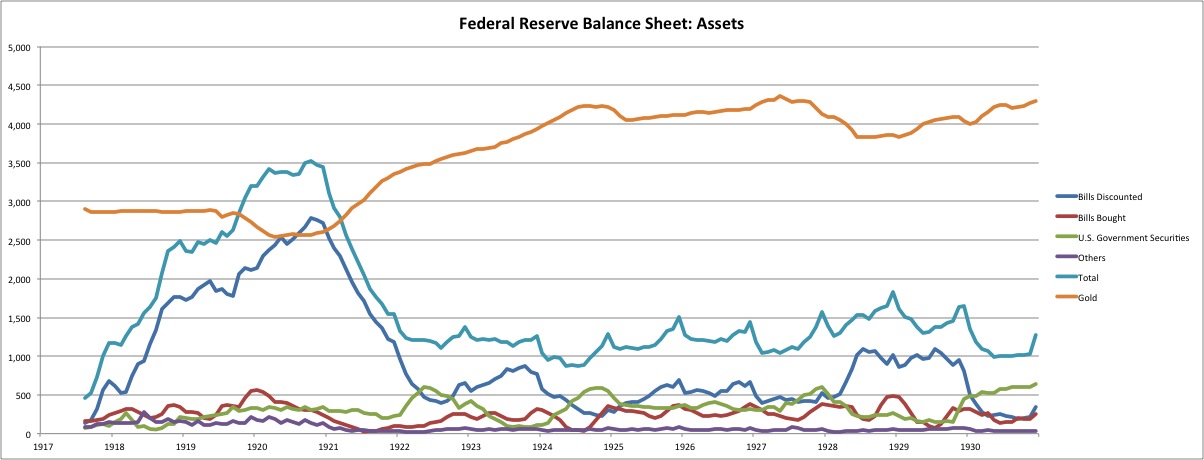

Here is the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet for the 1920s. There actually was a little bit of monkey business related to an expansion of Bills Discounted in 1928. This was the whole Benjamin Strong affair that Murray Rothbard liked to talk about. It really happened, but it was very minor. Also, you can see that the increase in Total Credit at the Fed was exactly offset by the decline in Gold, just as you would expect. The result was that Base Money was not affected at all. It was completely irrelevant.

See? Nary a ripple! Amazing, actually.

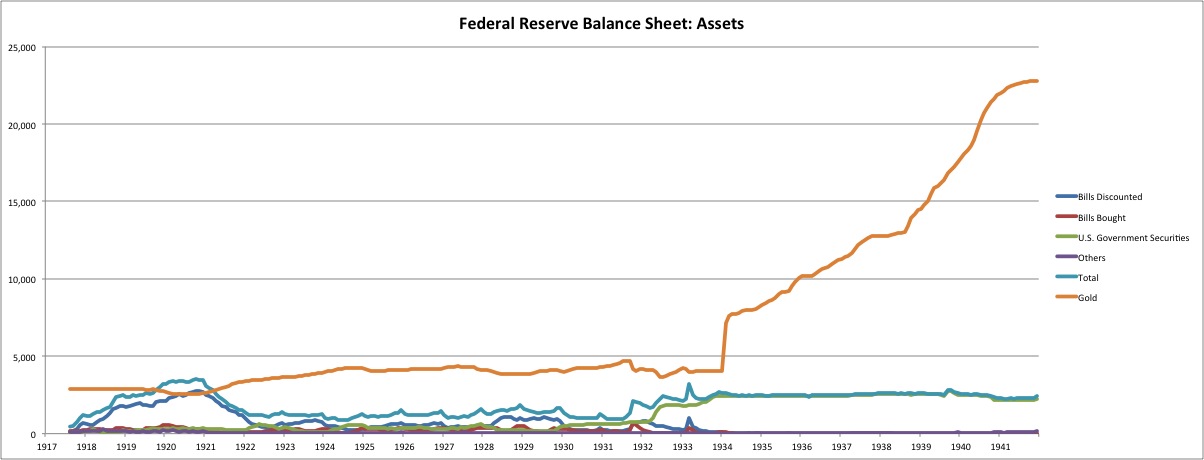

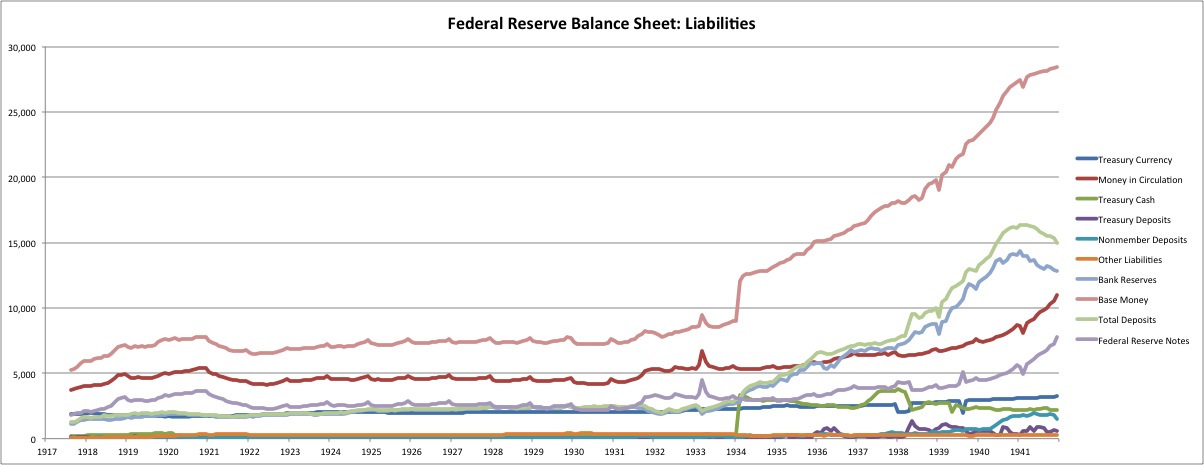

During the 1930s, there was no “contraction of the money supply” by the Federal Reserve, as Milton Friedman used to huff and puff about. Rather, there was a huge expansion after 1933, as risk-avoidant banks raised their reserve levels to very high levels. Following in the footsteps of Mises and the other Austrians, the “monetary contraction” that Friedman talked about was really the credit contraction (=Irving Fischer/Ray Dalio) that we looked at earlier. This was a big deal, but it didn’t have much to do with the Federal Reserve. The dollar remained linked to gold, with the devaluation in 1933 of course.

You can see here the increase in Base Money in the early 1930s. (The stepup in 1933-34 is due to the revaluation of gold reserves at $35/oz. instead of $20.67. The Treasury was credited with the increase in value, which shows up in the Treasury Cash account.)

So, to summarize: I have found nothing significant in the actions of the major central banks of the time, outside of the big devaluations including the Bank of England in 1931 and the U.S. Treasury (the Federal Reserve was not really involved) in 1933. Also, I think there was a very large Credit Bust in the 1929-1933 period, but this was not paired with a very large Credit Boom preceding. The Bust was basically a reaction to other problems, especially the Tariff War and the domestic tax hikes of 1929-1933.

Conspiratorially-minded observers have tended to blame the Fed for the Great Depression, suggesting that it was planned by the sorts of people who were responsible for the Fed’s creation in 1913. If there is merit in this line of investigation, I would look at the Credit Contraction at the banks instead of the Fed. You might even consider if all the focus that has been put on the Fed and other central banks, since 1930, might be an intentional diversion from the main story, which was the Credit Contraction.

I’ll get to Harwood soon.