Most people like lower taxes; the problem, potentially, is lower revenue. This is true on the Left, which naturally wants more revenue to fund all its big-government ambitions, and also on the Right, which is justifiably concerned about the dangers of large chronic deficits.

January 26, 2020: Evaluating The TCJA After Two Years

The nice thing is that, quite often, lower tax rates lead to higher revenues. This is basically due to two effects: 1) At a lower rate, there is less disincentive to pursue taxable activity, and thus the tax base expands. More taxable activity means more tax income. In practice, the revenue/GDP ratio of the tax does not fall in proportion to the reduction in tax rates, and may stay stable or even rise. 2) The economy grows more. This creates more revenue from all taxes, not just the tax whose rates were changed. On the spending side, lower tax rates often lead to less spending. When the economy is doing better, there are fewer people in need, and also, the spending-reduction crowd tends to become more politically dominant. Also, spending/GDP does down when GDP goes up, even if there is no change in spending. So, from either the revenue or the spending side, you can get a lot of advantages from lower tax rates. (I talk about all these things in more detail in The Magic Formula.)

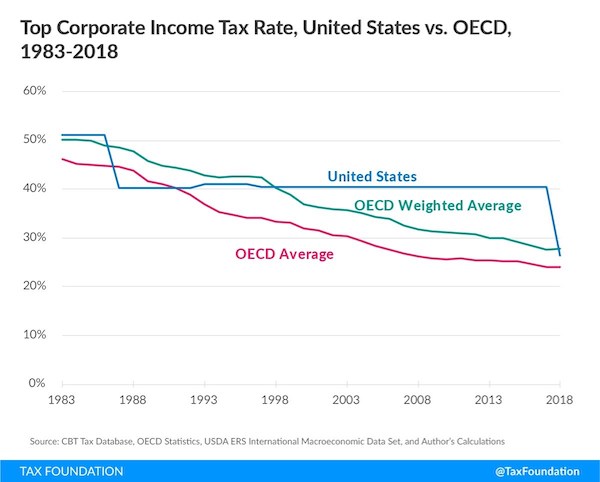

Last week, we saw that corporate tax rates have been coming down throughout the developed world.

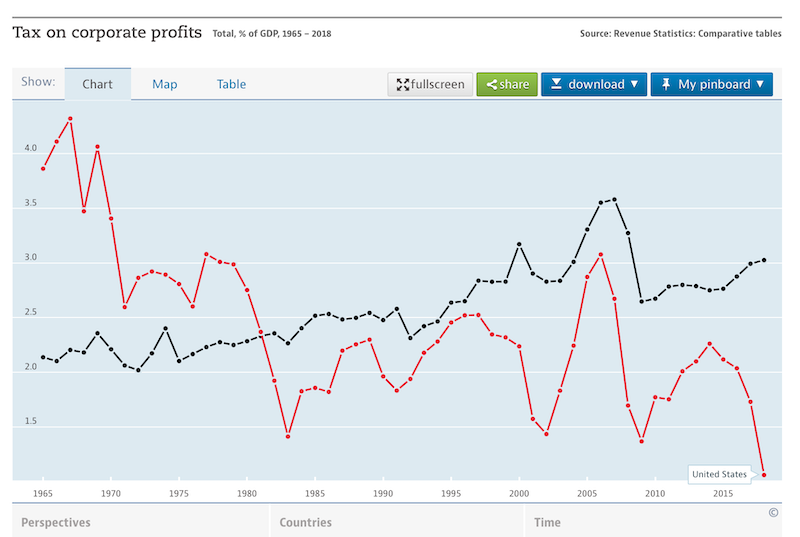

The result of this, on average, is that the revenue/GDP from corporate taxes has gone up, throughout the developed world. If you have a higher revenue/GDP (the increase from about 2.0% to about 3.0% is a 50% increase), and you also have a higher GDP (boosted by the lower tax rates), then you get big increases in revenue from lower tax rates. Hooray!

The revenue/GDP of the corporate tax in the U.S. has been rather low for years — actually, around 2.0% of GDP, which is also where it was in the rest of the OECD, when the rest of the OECD had corporate tax rates around where they were in the U.S. before 2018. However, since the TCJA in 2017, which lowered the Federal corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, revenue/GDP has not risen as it did throughout the OECD, but fell quite a lot. The tax rate in the U.S. is now about the same as the OECD average, but the revenue/GDP from the tax was recently about a third of the OECD average.

This is not due only to the change in the rates themselves. There was, among many provisions, an increased allowance for expensing capex in the first year, rather than depreciating it over time. The effect is lower taxes upfront, and higher taxes in the out-years since there is no more depreciation expense. So, any dropoff in revenue from that may be fleeting. But, also the change in rates was not accompanied by much reduction in exemptions and deductions, as was the case (for example) in the 1986 tax reform. The long period of high corporate taxes in the U.S. has led to many, many exemptions and deductions for corporations, as is usually the case in any high-tax regime. Lower rates are often accompanied by comprehensive reform including a reduction of exemptions, broadening the tax base — and this was probably the pattern throughout the OECD as tax rates were lowered. The idealized version of this is a Flat Tax, which typically combines the lowest possible rate with the broadest possible base. For example, many Flat Tax proposals use a “VAT base” principle, which is: Revenues – all payments to other companies – all employment expenses. In other words, all capex is expensed. But, interest payments are not expensed, and there are no targeted tax breaks for this, that and the other.

I think there is an opportunity going forward for another round of corporate tax reforms, in which the rate is lowered still further to 15%, which is what Donald Trump advocated in the 2016 election, but the VAT base is used. (Note that the total average corporate tax rate, including State and Local taxes, would be more like 19% with a 15% Federal rate. This compares to Britain at 17%.) This would eliminate all manner of exemptions and deductions for corporations, which are often used today to reduce tax payments to very low levels. (Could be zero, but since that carries headline risk, most corporations try to make a small notional payment.) Then, we might see revenues climb more toward the 3.0% of GDP level that other countries enjoy. However, this would mean that a lot of corporations whose effective tax rates are well below 15% would pay higher taxes, so it might not be so popular as one might think in the C-suite. But, the idea of making all corporations pay a proportionate share of taxes, without avoiding taxes through fancy accounting gimmicks and lobbyist-purchased legislative loopholes, would probably be pretty popular among voters as a whole, on both the Right and Left.

Many Flat Tax proposals include a “business tax,” which includes nonincorporated businesses, self-employed and passthroughs, basically anything other than employment income. At present, these are handled by the personal income tax. Thus, the revenue/GDP from a “Business Flat Tax” would probably be a lot higher than a “corporate profits tax.”

The main point of this warmup is that we could have still-lower rates, and also much higher revenues (revenue/GDP), which has been the pattern throughout the OECD over the past forty years. This would be a good thing overall. Nevertheless, there are a lot of people who still think that this is some kind of impossibility, which just goes to show how much familiarity they have with real-world outcomes throughout the developed world over the past forty years.

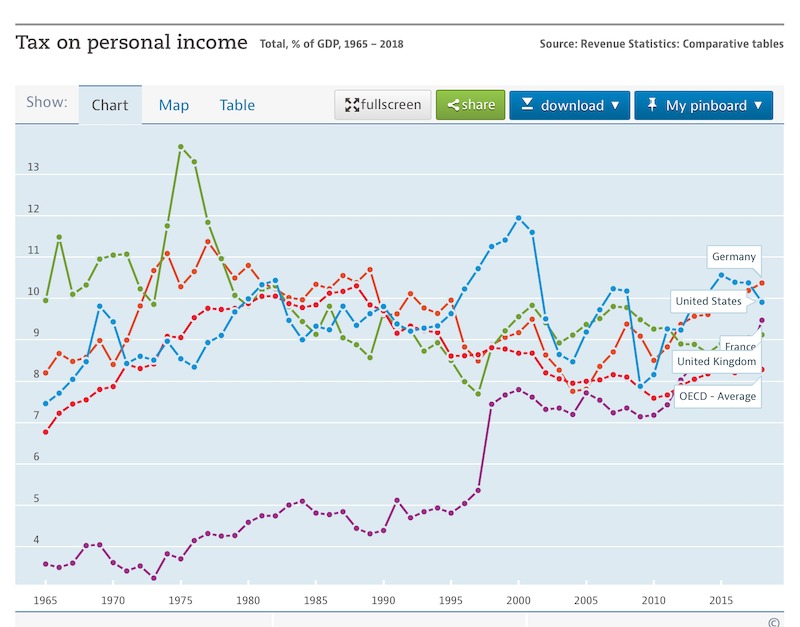

Since there were some changes to personal income taxes in the TCJA too, here is what revenue/GDP looked like through 2018. (This data doesn’t include 2019.) As we can see, the revenue/GDP from this tax in the U.S. was pretty high, in fact just about the highest in the world.

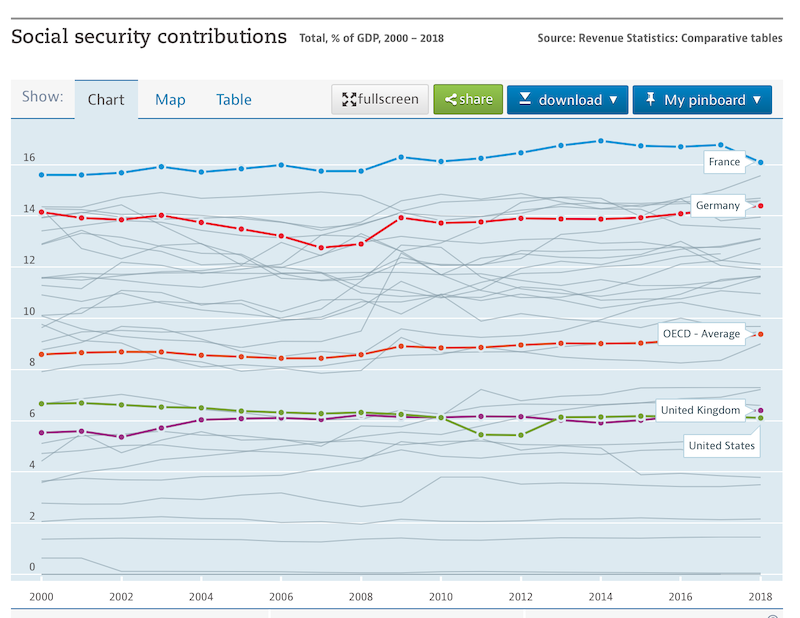

The thing that gives the European countries a much higher revenue/GDP ratio overall is not income taxes (“taxing the rich”), but payroll and VAT taxes. There haven’t been many changes to payroll taxes in the U.S. in recent years, so revenue/GDP here has been pretty stable. Note that payroll and VAT taxes are a) broad, b) simple, with little complication, and requiring no “tax return,” and c) a single rate, although there is often an upper limit on income to which they apply.

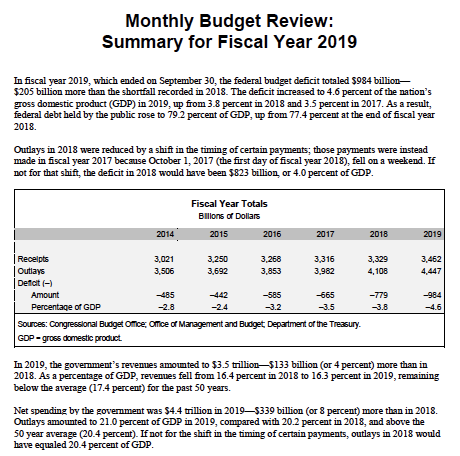

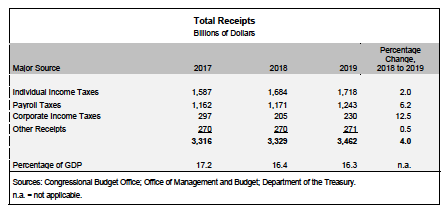

We now have some data for FY2019 (ended September 2019), so let’s take a look:

Receipts were up a little bit in 2018 and 2019. This is largely due to growth in nominal GDP. The overall effect was to keep up with the official inflation rate. According to Measuringworth.com, $3,316 billion in 2017 was worth $3,476 billion in January 2020.

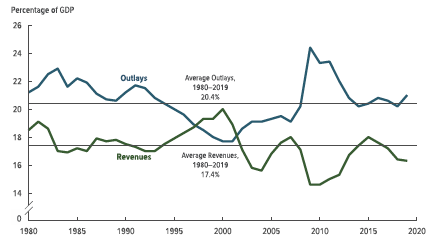

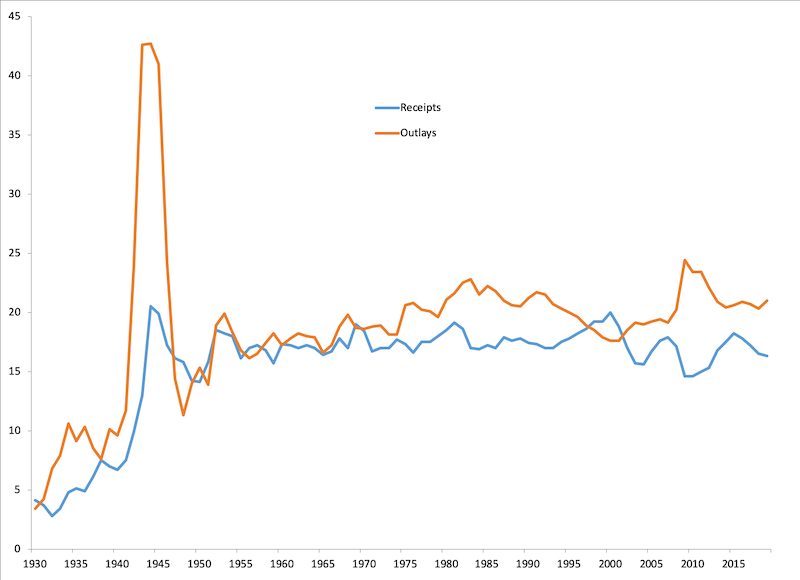

Revenue/GDP declined somewhat however, while spending/GDP rose. Here is a longer-term view, with the FY2019 actual results:

Tax revenue has been a little weak, but it is not so much different than its long-term average, which has changed surprisingly little over the years. Spending, however, is pretty high.

Corporate income tax revenue did decline substantially from 2017, not only in revenue/GDP terms but also in nominal terms. Nevertheless, the decline from 2017 to 2019 was a total of $67 billion, or 1.9% of total revenue of $3,462 billion. And, total revenues were boosted somewhat by higher nominal GDP due to the tax reform. If we say that nominal GDP is 1% higher in 2019 than it would have been without the tax reform (or about a 0.5% improvement per year over two years, 2018 and 2019), then that would mean about 1% of $3,462 billion increase in the revenue from all taxes as a result, or $35 billion.

Unfortunately, much of the budget is “nondiscretionary,” basically on autopilot unless there are some legislative changes, and these expenses grew at a rate much higher than the growth rate of nominal GDP.

Let’s compare to the Congressional Budget Office’s projections from June 2017, which reflected expectations before the TCJA:

Here is the CBO projection from April 2018, incorporating the TCJA:

I have to say that the 2019 projection, of $3,490 billion, was pretty close to the actual, of $3,462 billion. Here is a breakdown of the changes in the April 2018 projection.

We see that there are a number of “economic changes” that offset the “legislative changes.” I am not sure precisely what goes into “economic changes,” but as I understand it, the “legislative” is basically what we would call “static,” and the “economic” is “dynamic” effects.

In any case, pretty good predictin’. The CBO tends to be rather conservative in its economic expectations. This is reasonable, since they don’t want to make promises of bounteous future revenues that don’t appear. As Alan Reynolds observed, the CBO has tended to underestimate growth — including the growth effects of all the tax reforms of the 1980s — by about 1% per year. This is one reason why the “debt/deficit disaster” that many have worried about since the 1980s did not quite appear (although debts and deficits did get worse). 1% per year of extra growth has a big effect, in the longer term, even if it can be hard to see in the statistical noise from quarter to quarter.

In this case, I think that the overall economic effects of the TCJA were perhaps a little better than the CBO’s estimates (as has been true for a long time), but overall world economic conditions/other factors tended to offset that, so that the end result was pretty close to the CBO’s estimate. Related to that, we can ask whether the CBO’s June 2017 pre-TCJA projection (of higher revenues) would have actually worked out that way.

Here is a quick look at the CBO’s recent (January 2020) ten-year projections.

The expectations for economic growth here are, as has long been the CBO’s tendency, pretty modest. It would not be hard to exceed this, with some good growth-friendly policy, just as the economic performance of 2017-2019 has exceeded this. On the other hand, there is also a risk of recession sometime, which would have growth below this level.

The low growth expectations are due in part to the decline in the labor force due to retiring Boomers.

Big deficits. Basically, this is “nondiscretionary spending”, mostly healthcare and Social Security, plus the interest on the large existing debt.

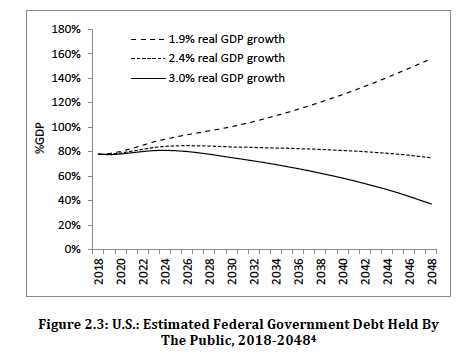

This might not go well. Remember, this is the outcome of low growth. At 3.0% real growth, a lot of these problems disappear.

Tax revenue, as a percentage of GDP, is actually expected to rise throughout this process. This is basically “bracket creep,” as people end up in higher and higher tax brackets (due to real growth rather than “inflation”), plus some phaseouts of existing tax reductions (basically, future tax increases). But, that would result in a historically high revenue/GDP for the individual income tax, which might not happen basically because people will, one way or another, avoid paying those higher taxes. This has been the pattern throughout U.S. history.

Higher spending.

Although the viability of today’s present spending would be improved by higher growth (as GDP gets bigger, expenditures/GDP falls), nevertheless I think that it is coming time to reform these decrepit institutions, and not just let them rot in place because we are too lazy to do anything about them, even if we could if we had higher growth. The approach should be a combination of Lower Taxes and Lower Spending. “Lower Taxes” mostly means lower tax rates, while the revenue/GDP ratio might stay the same or even climb, as for the proposed corporate tax reforms mentioned earlier. In short, “Growth” in the form of lower taxes/tax reforms, and “Austerity” in the form of lower spending/GDP — if you want to put it in those terms.

The CBO is expecting a little higher debt service payments. But, it could be quite a bit higher.

All in all, the large drop in revenue/GDP from the corporate tax (without any recession) is somewhat problematic. It would be nicer to have lower rates, and also a higher revenue/GDP, maybe a lot higher, as is the case elsewhere. The increased revenues could help justify further reforms of individual income taxes.

On the individual side, we would like to have lower rates of course — I think a 25% top rate is doable — and also, the elimination of capital-related taxes such as capital gains taxes, and taxes on interest and dividend income. Dividend income is already taxed at the corporate level. Interest income would also be taxed at the corporate level, instead of being expensed as it is today. Capital gains is basically a type of wealth tax. Against this, we could reduce exemptions and deductions substantially, including a full elimination of State and Local Tax deductions. It might be worthwhile to consider making employment compensation in the form of healthcare and other benefits taxable. Basically, this is the “VAT base” as applied to the individual income tax, and has implications for the reform of the present healthcare system.

One of the longstanding objections to eliminating capital gains taxes, and also in favor of taxing capital gains as regular income (at high rates), is the tendency for income that is basically regular business or employment income to be taxed as if it was capital gain, when it is really not. A particularly noteworthy example of this is the carried-interest provision for investment fund managers. A solution here would be simply to tax it as regular business income, since that is what it is: compensation for fund management services, not wealth that has already been taxed as either corporate or individual income. But, since the tax rate on regular business income (in my example here) might be 15%, or the present 21% corporate income tax rate, instead of the present 20% capital gains tax rate, I think that would not get too much pushback. This follows, for example, the treatment of employee stock options today, income from which is treated as regular employment income when they are exercised.

For now, there is talk of “tax reform 2.0” from the Trump team, but the mood in Congress is that it would be hard to push this through successfully while spending is unreformed and big deficits are on deck out to the horizon. Democrats don’t want program cuts, and Republicans are worried about deficits. You can do “revenue-neutral” tax reforms that can actually be a big help, as was the case in 1986. Unfortunately, although these “revenue neutral” approaches can actually lead to some substantial improvements from which everyone benefits — it is not a zero-sum game in real life — they tend to be politically difficult, because in whatever accounting system is used, the number of “winners” tends to balance out the number of “losers” (that’s how it ends up being revenue-neutral), leading to political gridlock. In other words, it is framed as a zero-sum game, and this narrative tends to become overwhelming. A more politically feasible approach is to give nearly everyone an apparent tax break, even if it may be smaller for some and larger for others. But, a reform of corporate taxes that brings revenue/GDP more toward OECD norms, while keeping rates low, might provide a “budget” to do some helpful tax reductions on the individual side.