I thought that I would take some time to evaluate the effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which, among many items, reduced the Federal corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. These effects can be split into economic effects, and revenue effects.

It takes time to evaluate tax changes. Even after they are enacted, the effects take months and years to be felt. For example, the deadline for corporations to file their 2018 taxes was September 15, 2019; and the results of this won’t be evident in public data until some time after that. Before any tax change, there is inevitably a lot of discussion, and before long this discussion involves a lot of detailed claims and projections. People tend to assume that the claims and projections bandied about during the discussion period (which was mid-2017) are what really happens. But, what really happens often differs quite a bit from the discussion-period-era claims and projections. (However, in this case, it appears that the various mid-2017-era claims and projections were actually pretty accurate.)

All in all, I think the policy was a very good one. Looking at the data, however, the measurable results are something of a muddle. The economy has been fairly strong, although not very strong. I think that the economy is markedly stronger than it would have otherwise been, but that is ultimately just a guess. Nevertheless, all the data for employment and wages have improved, and the economy has managed to avoid recession in an environment where other major world economies have slowed substantially.

Daniel Mitchell, who has followed these things in detail over the years, had an excellent summary of the TCJA. He referenced a WSJ op-ed by former Trump officials Gary Cohn and Kevin Hassett. The Tax Foundation has good analysis of the TCJA, but hasn’t updated its evaluation of the results for a while. Here is a brief update from Adam Michel at the Heritage Foundation. It doesn’t seem like there has been much from Cato, including anything from Alan Reynolds. Borrowing from Mitchell’s post:

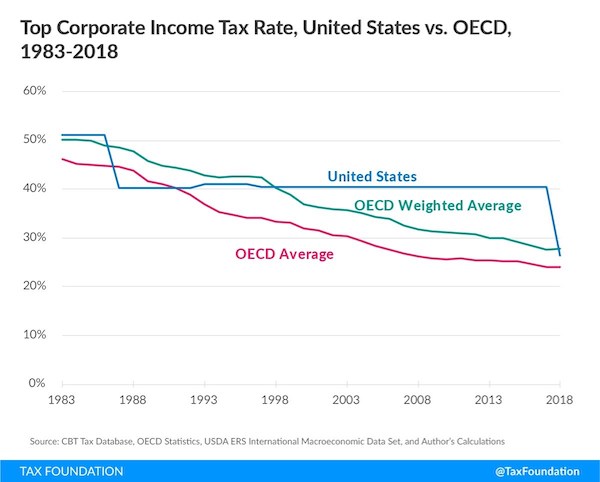

The tax reform lowers U.S. taxes only to about the norm for the OECD these days, where there has been a long trend toward lower corporate taxes. As I argued in The Magic Formula, one reason why other OECD countries can get by with a higher “tax burden” (revenue/GDP ratio) is because their taxes on business, capital and investment have been generally lower. They raise revenues with VAT/payroll taxes, which have much less destructive economic effects.

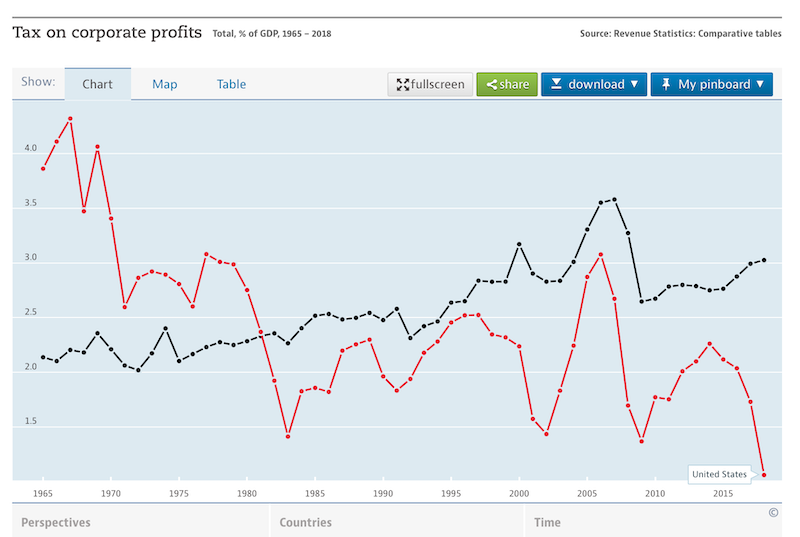

This trend toward lower corporate taxes has been accompanied by a trend toward higher revenue/GDP from corporate taxes, throughout the OECD. The big decline in U.S. revenue/GDP from corporate taxes in 1965-1980 was not due to lower rates, but the narrowing of the tax base (deductions/exemptions), likely prompted by high tax rates. However, the decline in U.S. revenue/GDP in recent years (related to the TCJA) is dramatic, and contrary to the experience of other countries. Other OECD countries have about the same tax rates as the U.S. today, but about three times the revenue/GDP. We will talk about this more in the revenue section, since we are supposed to be talking about economic effects for now.

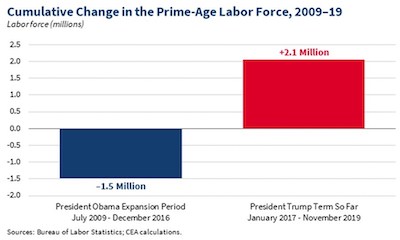

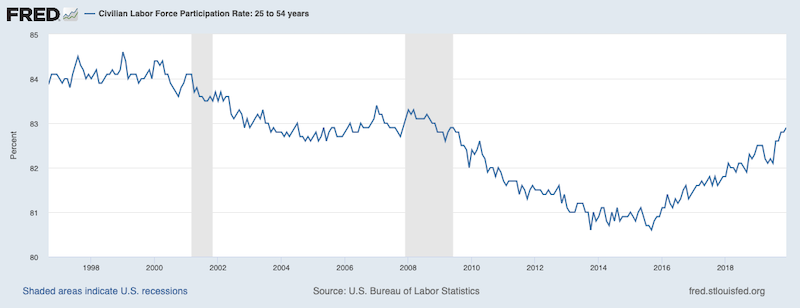

Labor force participation (a better measure, in many ways, than the official unemployment rate) took a nice lift higher.

Wages, especially for lower incomes, have been doing the best in many years.

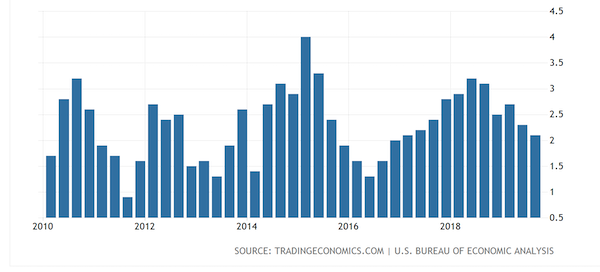

There was a nice lift in GDP in 2018, but this cooled afterwards.

By the numbers, the average compounded growth rate for real GDP during 2009-2016 was 2.1% per annum, and from 2017-2Q19 was 2.6% per annum. This is a rather modest amount of improvement, which tends to disappear in the statistical noise. Nevertheless, an additional 0.5% per year is actually a big deal, and adds up over time. But, if you consider that, given the severity of the 2008-9 recession, there should have been a big rebound with above-trend growth (in past recoveries this often exceeded 5%), the 2009-2017 figures are especially bad, and the 2018-19 relatively better by comparison.

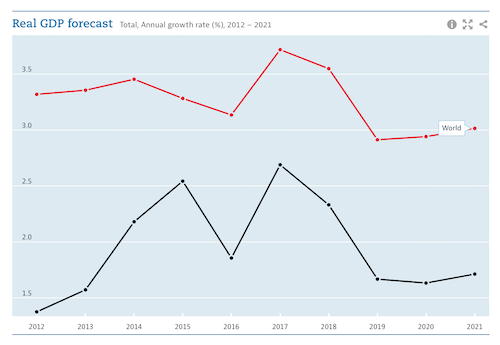

This has been taking place while economies around the world have been slowing. So, just to keep even has been an accomplishment.

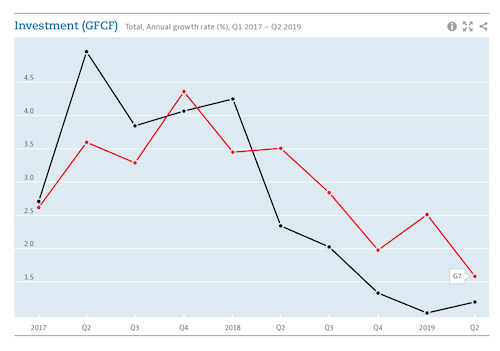

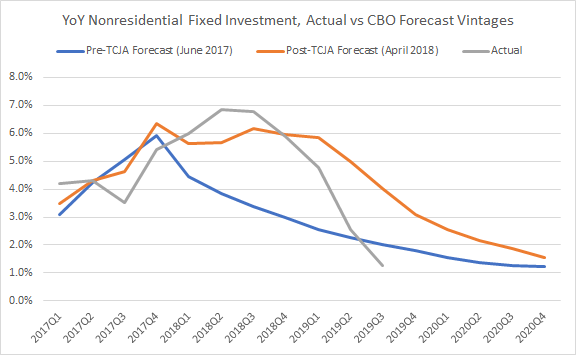

Capital investment had a nice surge in 2018, but cooled afterwards along with cooling economies worldwide. There has been some criticism that too much corporate cashflow is going into share buybacks, rather than capex, resulting in mediocre job growth. I agree with this, but I don’t think that the TCJA can be blamed for that.

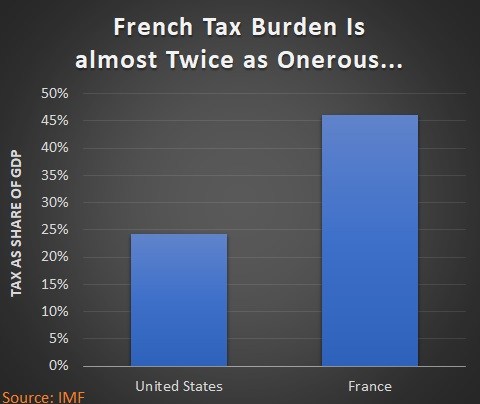

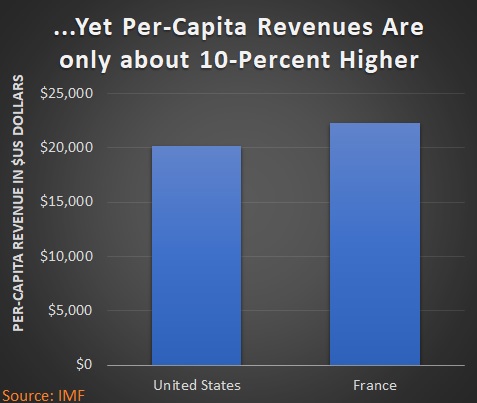

As I described in The Magic Formula, over time, a country with higher growth — even if it is only a little higher — will eventually have higher tax revenue at a lower tax rate and lower revenue/GDP “tax burden.” For example, U.S. per-capita tax revenue is now about the same as France, even though France has a much higher revenue/GDP.

Lower taxes leads to more revenue, which can fund more social services — while at the same time, there is less distress and less pressure for socialist solutions, because people can get by on their own. These tax changes, like the TCJA, might seem to have modest effects over one or two years, but over two or three decades, they can make all the difference.

I think that is enough for now. On balance, the results have been somewhat moderate, but pretty good. I think we have been notably better off than if there had been no change in tax policy, and I think most Americans sense that this is true.