(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on April 24, 2020.)

For many years, many people (including myself) have warned that we could enter a period of hot crisis, similar to that described 23 years ago by William Strauss and Neil Howe in their book The Fourth Turning. Now, that crisis is here. It is not really a matter of a viral disease in itself, which might not actually be all that deadly — just as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in 1914, might not have caused much turmoil if the surrounding conditions were different. The real crisis is our response — a response which, to some eyes, looks like a total collapse of responsibility, good judgement, and functioning institutions.

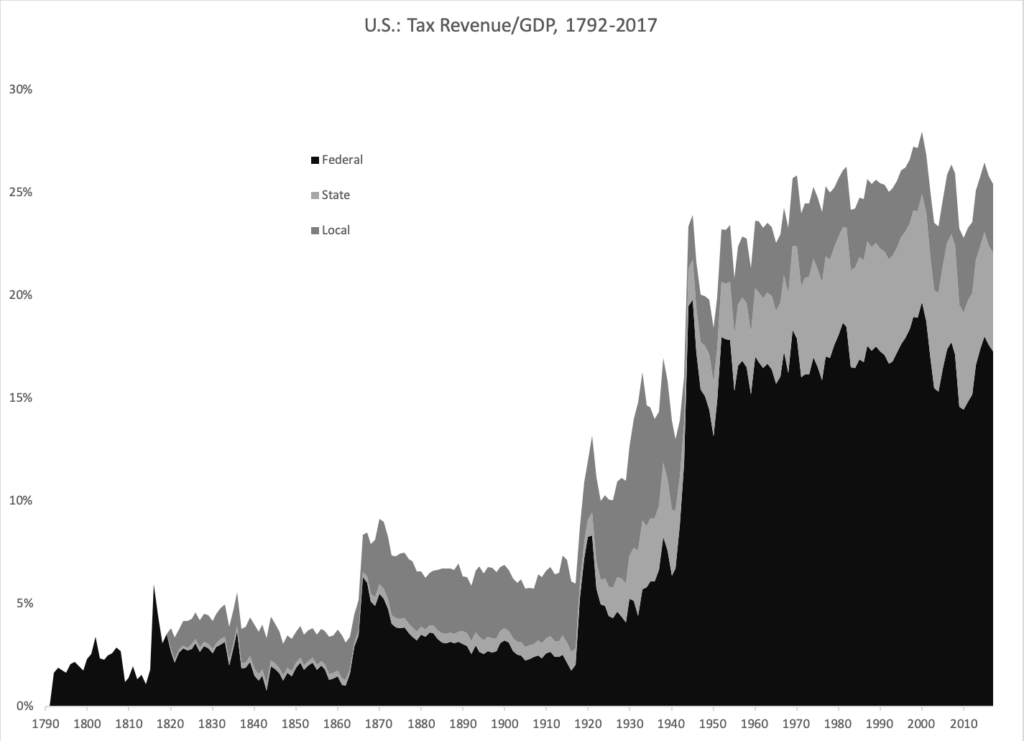

I think these consequences will roll forward for many years after virus-related “lockdowns” have been lifted. One aspect is the seeming nonchalance about running Federal budget deficits on the order of 15%+ of GDP; another is the heavy hand of intervention in financial markets and direct corporate operations. You could add a lot more to this list I am sure.

But my focus today — and, in my recent book The Magic Formula (2019) — is not on this crisis, but what comes afterwards. One consequence of seeing our existing institutions crumble like so much rotten timber is that we will be able to create new institutions. Before, this was politically impossible. Soon, it will become politically necessary.

The last time this happened was soon after World War II. Out of that time came the large Federal government we have today — a Federal government much larger even than that of the New Deal era of the late 1930s, much larger than that of the 1920s, and much, much larger than that from before 1913. We got the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, establishing principles for a world monetary system, along with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank; the United Nations dates from 1945; the Central Intelligence Agency from 1947. We retained a large standing army with bases throughout the world. This postwar period also saw the rise of the automobile suburbs; widespread attendance at universities and high schools (only 30% of young Americans graduated from high school in 1930); and television. Social Security became a giant institution, to which was eventually added Medicare and other healthcare and welfare programs.

I think it is time now — since many of us have a lot of free time — to think about these new institutions, and the eventual recovery from our crisis era, a number of years from now. The United States recovered from World War I by returning the dollar to a gold standard at $20.67/oz.; by lowering the top income tax rate from a wartime 77% to 25%; and rolling back a broad swath of Federal wartime controls on industry. Russia responded to World War I with the Soviet Union. Both came about because people at the time had certain ideas in their heads; some worked well, and others didn’t.

One of my recent enthusiasms is to describe new modes of education. We’re all homeschoolers now — have you noticed? — and some people are discovering that they like it. (Especially children.) On my website, I’ve been describing how the proven homeschool model can be extended to undergraduate-level education. This is actually the original model of college education in America — Yale University began with one man (Abraham Pierson, 1701), a shelf of books, and one student. It took place in Pierson’s living room. As President James Garfield said: “The best college is Mark Hopkins on one end of a log, and a student on the other.” (Mark Hopkins was president of Williams College while Garfield was a student there.) Yes, an eighteen-year-old student could theoretically educate themselves with the help of a library; but, in 1701 just like today, this rarely actually happens. A guide is needed.

Automobile suburbia, like the Soviet Union, is one of those ideas that didn’t work out so well, if you ask me. I have proposed a return to the traditional form of the walking-based city, which is common throughout Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and today is considered so beautiful that people get on planes to visit these cities during their vacations. The post-Crisis-Era city will be a beautiful and quiet place where you can live without a car, and where walking, cycling and public transit are the primary modes of travel. Already cities like Paris and Milan are making major changes in this direction — becoming much more like Paris and Milan of the past. The government of Paris just introduced 650 kilometers of segregated bicycle lanes, supposedly a response to the present crisis, but also something that had been on their minds for a long time earlier.

In terms of post-Crisis economic policy, I suggest the Magic Formula: Low Taxes and Stable Money. If you think about it you just might get it; just as Parisian cyclists are suddenly finding the world remade to their order. Stable Money ideally means some kind of gold standard system; the traditional way that monetary stability has been achieved for centuries. I wrote three books about the gold standard system, because I knew that when the time came and people asked: “What are we going to do about this monetary disaster?” you couldn’t answer: “Let me write a book about that and get back to you in two years.” The ideas have to be in people’s heads, for a long time earlier, and then they appear in the world when the time is right.

People have talked about Low Tax solutions for decades, including the Flat Tax and the FairTax, a national sales-tax plan that eliminates income taxes altogether. These proposals were both timeless; and, products of their time. In the 1980s and 1990s, people considered the spending side of the Federal government too difficult to change, so the idea was a complete reformation of the tax system while leaving spending largely intact.

Today, the spending side of the Federal government is a dumpster fire. When people get tired of printing money to solve every problem (it is just a matter of time), then we will be able to do a complete reform of the taxing and spending sides of the Federal budget together.

In the late 1940s, under U.S. military occupation, the Japanese and German governments both used the printing press to finance governments that were otherwise destitute. This caused eventual hyperinflation in both cases. The eventual solution (it was promoted by Joseph Dodge, a Chicago banker who traveled to Japan and Germany in that time) was for the governments of Japan and Germany to strictly outlaw all debt issuance. They had to run their governments on current cashflow only. This relieved the pressure on the central banks to finance deficits, which then allowed both Japan and Germany to return to the gold standard in 1949. Japan’s outright ban on debt issuance lasted until a recession in 1965. Japan’s great postwar economic recovery happened without a whiff of Keynesian deficit spending. In China, the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-Shek also used the printing press to finance deficits; the resulting hyperinflation led to Mao Zedong’s Communist Revolution in 1949. One of Mao’s first steps was also to reintroduce the gold standard in China, also in 1949. Mao’s other ideas didn’t work so well.

I think the best course, and also the easiest course, of this reform of Federal spending will be an active embrace of Tenth Amendment principles. Healthcare, education and welfare programs should all be made the sole responsibility of State governments. This might seem unlikely, but it could become very likely very quickly when we sign the law that prohibits all Federal debt issuance. All that this devolution requires is to shut down the Federal programs; and let the States fend for themselves, taxing and spending however they wish, within the limits of their own State constitutions.

State politics would get very interesting. They would also get a lot more democratic. The average State Congressman of Massachusetts has 41,000 constituents; the average Congressman of the Federal House has 747,000. Plus, you could probably visit your State Congressman’s office this afternoon, while your Federal representative spends half his time in Washington DC.

This would be a much smaller Federal government, spending perhaps about 10% of GDP, and possibly even less. This Federal government could be financed with a very low and simple tax. Something like a 10% Flat Tax could work, but I think we should go for it and introduce a 10% VAT (basically a Federal sales tax), and repeal the Sixteenth Amendment. (Tax technicians note that there is actually very little difference between some Flat Tax proposals and a VAT.)

Yes, we will make changes to the Constitution. As the floorboards collapse beneath them, a broad swath of centrists voting either Republican or Democrat, but mostly in favor of keeping things mostly as they are, will find that they have to make some hard decisions based on principle rather than expediency: basically, Bernie Sanders or Ron Paul. They will move toward Ron Paul because, despite the influence of their Marxist professors in college, they are still Americans.

People today don’t understand what “Liberty and Freedom” meant in 1789, in terms of economic policy. It meant: No direct taxes such as an income tax, and money that was not fiat government scrip printed to meet spending needs, but based on gold and silver. These are in the Constitution in Article I Sections 8, 9 and 10. The United States Federal government was supposed to be funded with indirect taxes such as a retail sales tax, tariffs or VAT. Taxes were supposed to be “uniform” (the “uniformity clause” in Article I Section 8), which means that everyone had the same tax or tax rate — like a sales tax or VAT today. You weren’t supposed to have different tax rates for different people, which is the basis of the income tax, and which has been causing unending problems since its introduction in 1913. Pretty soon we had the majority voting to spend the minority’s money, exactly as Benjamin Franklin predicted.

But, I think people are going to relearn these principles — the hard way!

Retirement income and healthcare are two big topics where I think people would not be willing to go back to pre-1913 principles of strict personal responsibility. A good solution is presented by Singapore, which makes aggressive use of the “provident fund” system. Basically, this is a mandatory contribution to something like a personal 401(k) account, and a health savings account. These are supplemented by various supports if they prove to be insufficient. Singapore’s healthcare system is by far the best in the world today. It makes used of health savings accounts with mandatory contributions, active shopping in a free market system with public prices for everything, high-deductible insurance programs, government subsidies for lower-income people and universal healthcare access with the same doctors and same hospitals that everyone else uses.

Of all our “institutions” today, the one I am most happy to see disintegrate (vying closely with higher education) is the U.S. healthcare system. Singapore’s system provides some of the best outcomes in the world, at a total cost of 4.2% of GDP, compared to 10.6% in the OECD as a whole and 18.0% in the U.S. The government’s share consists of 1.5% of GDP, compared to the U.S. now at 8.5%. Doctors get paid roughly the same as their U.S. counterparts. A Singapore-like system could be implemented at the State level, leaving the Federal government out of it except perhaps in some regulatory matters.

Singapore also has mandatory provident funds for housing and education, which might be a case of taking a good idea too far.

After a long period of war and hyperinflation, in which the old order was well and truly blown to smithereens, some Americans got together to decide what to do about it. They created the United States — a new country based on the Magic Formula of Low Taxes and Stable Money. It became the most successful country of all time.