Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

March 7, 2010

I suppose Suburban Hell is not really a place we need to take a trip to, because we’re already there. Indeed, it has become so familiar to us, and so invisible, that people don’t really think about it at all. What is Suburban Hell, anyway?

We’ve been talking about the failure of 19th Century Hypertrophism, big city variety, in the United States. This was a new format, more or less invented in the U.S., and it has been mostly a flop with the possible exception of Manhattan. However, even in that case, I would say that it has not produced a comfortable lifestyle for the majority of people. (The very wealthy manage to have a good time wherever they are.)

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

This failure of large cities in the U.S. has two components, as I see it. The first component is the design of the city itself. The combination of very large streets and big, cold, blocky buildings was not very friendly to humans, compared to the Traditional City found in all European and Asian examples up to that point. However, with that we combine the general atmosphere of cities in the U.S. during the 19th century: an environment of capitalist exploitation and wave after wave of immigrants. These immigrants were both migrants from foreign countries and migrants from agricultural regions of the U.S. (notably blacks from the South). The fact of the matter is, as farming became more and more productive, more and more people had to leave farming areas and take up a new lifestyle. On top of all this, population was expanding rapidly, adding more and more people to the labor pool. In 1870, 70%-80% of the population of the U.S. was employed in agriculture. Today, it is about 2-3%.

Try to imagine this mass migration into the seething, stinking cities, this messy conglomeration of huddled masses (their term) from all over the world, all trying to make a new living in the factories where there were no labor laws, no minimum wage, no days off. Industrialization was no picnic in London. In his review of Western Civilization, Kenneth Clarke considers the period the time of greatest peril for European Civilization since the mongol invasion of the fourth century. At least in London, everyone spoke English, and had some cultural background in common. In the U.S., it was dog eat dog. A heavy black coal soot hung over everything. Sewers, water supplies, sanitation and so forth were taxed to their limit. Not much in the way of a social safety net existed. Crime and gangs were everywhere. All of this combined to make urban environments that were plainly unpleasant, and which did not easily develop an urban culture to go along with the independent farming family culture that made up the core of the American self-image.

All of this is a long way of saying that people wanted to go back to “Small Town America.” For Americans that were not recent immigrants, it was where they came from. Their experiments with urbanism were a failure. What is “Small Town America”? By definition, a small town is a town that is surrounded by something that is not a town. Small Town America was surrounded by farms. It was the place where farmers educated their kids, bought supplies, went to the theater, and so forth. Small Town America provided the civic infrastructure for agriculturalists. There was a little industry, but the heavy industry was taking place mostly in Big City America.

However, they couldn’t go back to Small Town America, because they weren’t farmers anymore. The jobs were in the big city.

Small Town America had another feature. 19th Century Hypertrophism, small town edition, had a funny aspect. These small towns were nothing like the small towns of Europe or Asia, where Traditional City designs held sway even in very small villages. Residences in Small Town America were identical to residences in the surrounding countryside. In other words, they were farmhouses just like the houses you see on the farm.

Suburban Hell consists of two basic patterns:

2) Commercial areas that are optimized for automobiles.

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

Today, there are many self-proclaimed New Urbanists who hold up Small Town America as their design ideal. The problem with this is that a) Small Town America is itself a dysfunctional 19th Century Hypertrophic format; and 2) Small Town America is also the model for Suburban Hell!

You know what the result will be. Failure failure failure. It’s inevitable.

New Urbanist types like to talk about “density,” but the fact of the matter is that many suburbs today are more dense than Small Town America. Because there are lots of people in a big city (by definition), land is more scarce and thus more expensive, so house plots tend to be smaller.

Actually, the “suburban” free-standing farmhouse on 0.25-0.5 acre is very much a part of the 19th Century Hypertrophic model, big city version as well. People’s first choice then too was to live in a suburban style farmhouse. However, they didn’t have cars in those days. They needed to walk to the train, or wherever they were going. They couldn’t just build houses anywhere. This drove the process of densification, where freestanding houses might be replaced by side-by-side townhouses and then apartment buildings. Although they wanted to live in a suburban farmhouse, they couldn’t.

This probably seems quite natural, but actually it is unusual. We don’t see it as much in Europe or Asia. There, we see villages that adopt a fully urban format from the beginning. Everyone lives in Traditional City type structures, even in a small village.

Obernai, a village in the Alsace region of France. Even the smallest villages use the dense Traditional City format.

A typical Obernai street scene. Classic Traditional City design. Lovely colors!

No cars!

Obviously NOT single-family farmhouses on quarter-acre plots.

You’ll never find a Small Town in America that looks like this.

However, it is quite common in the rest of the world. This is a village in China.

Small Town America looks like this!

Dore Cottage, built in 1869. Located in Riverside, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago designed as a “planned community” (I kid you not) by Frederick Law Olmstead.

W.T. Allen House, Riverside (1869). Pretty much your standard suburban farmhouse-surrounded-by-grass-on-a-quarter-acre.

Nothing has changed in 140 years. Nothing!

The difference between then and now, of course, is the automobile. This vastly enabled the expansion of this suburban-style development, because it was no longer necessary to be able to walk to wherever you were going, or to the train station, or to have a bunch of servants to maintain a pair of horses and a carriage. It wasn’t until the 1920s that automobiles became widely affordable, with the Ford Model T. Suburban development soon followed, but was cut short by the Great Depression and World War II. Thus, the big explosion of automobile-enabled suburban development followed World War II.

Now everyone could live in the Small Town America suburban house of their dreams! They could finally escape the hideous, stinking, rotten dysfunctional cities.

The cities had become such a mess that people wanted a buffer between them and the city. This seems so natural to Americans now that they probably think it is a law of nature. Not so. In a city that is inherently pleasant, there is no need for a buffer. The suburban farmhouse seemed to have a sort of buffer built in — the strip of mowed grass on all sides, to separate the family from the dysfunctonal 19th Century Hypertrophic City.

The problem was then the commercial areas. Although the 19th Century Hypertrophic model (“Small Town America”) includes a humungous roadway, it is still basically a walking-based construct. There is a little parking on the road, but not much. This was passable in the 19th century, because only rich people had cars. Most people walked from their house to the stores, offices and so forth. Who does all the shopping? Women do, mostly. And how many women like to parallel park?

Stores didn’t need parking because their customers didn’t have cars. When everyone had a car, all the stores needed parking. In fact, they probably wanted to put it out front, visible from the street, as if to say: “Hey Mrs. Smith! Check out our abundant free parking!” Have you noticed that nobody hides the parking in the back? Plus, the parking lot itself became a buffer between the store or office and the six roaring lanes of traffic in the middle.

Of course the roadways had to get bigger. The typical 19th Century Hypertrophic street, wide enough for about one lane in either direction plus a layer of parallel parking, was not nearly enough when the middle class got their automobiles. Now we needed two lanes in either direction, plus left turn lanes, plus a shoulder for breakdowns and so forth.

However, the on-street parking disappeared due to the introduction of parking lots, so actually the roadway didn’t get that much wider. It did get a heck of a lot noisier, though, with constant traffic rather than the occasional rich person puttering around in his “horseless carriage.”

Imagine the commerical area of the typical 19th Century Hypertrophic City. Here we have a very large roadway (by Traditional City standards), but rather nice Traditional City style buildings. The roadway was mostly empty in those days, before automobiles, so it was reasonably pleasant although a huge expanse of dirt in the middle of the city. Most people walked to work, and to do their business. It was tolerable enough.

However, now we have an immense amount of automobile traffic, on a newly-expanded roadway, and then an immense amount of parking everywhere. What comes next?

Green Space!

And zoning.

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

The reasonably pleasant commercial (retail, offices) areas had become a Frankenstein monster. The next step was to try to dilute all this concrete and asphalt with some greenery. This followed the basic pattern of the suburban house itself, with its green buffer all around.

We begin to find, around this time, that the residential areas want to distance themselves from the commercial areas and their heavy automobile traffic as much as possible. In the 19th Century Small Town America, people built their houses right on the largest street, Main Street. (I live on Main Street in a 19th Century Small Town America.) They even built porches so they could watch the occasional wagon roll by, and say hello to their neighbors. This didn’t work so hot when automobiles were introduced. On the Main Street that I live on, I don’t think I’ve ever once seen a “traffic jam.” There aren’t that many cars. However, what little traffic there is, is plenty to be audible inside the house all day long. The constant roaring of automobiles. Today, the houses on Main Street in my town are less desirable (and cheaper) for that reason. Plus, cars zooming by are plain dangerous to little kids, pets and so forth who might step into the road for all kinds of reasons.

In Suburban Hell, the residential areas retreat from Main Street as far as possible. The suburban cul-de-sac is introduced, breaking the pattern of The Grid that dominated the 19th Century. The cul-de-sac ensured that the only people that would be using the residential street would be the residents themselves. Also, traffic speeds would be kept low, since there was nowhere to go.

Recent residential development in Las Vegas. The house plots are much smaller than the typical Small Town America format. Notice that we have lost The Grid and have adopted a curvy, biomorphic layout. However, the Heroic Materialist ideal of factory mass production remains.

Next comes zoning. If the commerical areas a huge mess, let’s make sure they are nowhere near my house and family. Let’s make sure nobody in our residential area operates a business, which might bring more auto traffic, and people trying to park on the street and so forth. Do you want to live next to Home Depot and its two-thousand car parking lot, and six lanes of traffic? I don’t think so. Besides, when everyone has a car, it is not such a big deal if the closest stores are two miles away. In fact, I kind of like it that way. Thus, the logic of automobiles leads to complete automobile dependence. It is no longer possible (realistically) to walk from the residence to the commercial area, for shopping or working.

Once you can’t walk anywhere, then buses or trains become unusable, because you can’t walk to/from the bus stop or train station to anywhere you need to go.

We see some other patterns happening here. Since everyone has automobiles, they can carry a practically unlimited amount of merchandise. When people walked, they may have shopped every day because they carried their purchases by hand. They needed to live within walking distance of the grocery store. Now, they could stock up in size. A carton of copy paper? No problem. Two hundred pounds of groceries? Why not. Stores themselves became more and more like warehouse distributors.

And there you have it. Suburban Hell in all its craptastic horror.

I would guess this is actually pre-WWII suburban development — possibly from the 19th century, predating automobiles. Bridgetown, Ohio. Note the much larger house plot size. This is closer to the Small Town America format. Small Town America has big yards!

Anacortes, Washington.

Recent development in Arizona.

Arizona.

We are coming quite close to townhouse-type development here — a common Traditional City format. U.S. cities have gotten so large now (due to suburban sprawl) that the automobile is no longer able to open up a practically unlimited supply of new space. Land has become scarce again, and travel time is important. However, it is still unwalkable due to zoning, and rather excessive auto-dominated roadways. We still have that buffer of grass in the front. We have some small backyards here, which is another fine Traditional City element as long as it doesn’t get out of hand. (It doesn’t look like anyone is using their backyards much. What if there was a nice little park every ten houses instead?)

Proper townhouse development wouldn’t have a lawn and a driveway in front.

Here are some nice 19th century townhouses in San Francisco. This has a strong whiff of Hypertrophism about it (notice the huge stairway again), but it is a pretty good model of what could work in the future. These even integrate a garage nicely, so the owner can have a car if they wish. (The garage can even hold two cars parked end-to-end.) The roadway is much too large, however.

For example, here’s a residential street in the Jiyugaoka area of Tokyo. People here have cars, as we can see, but the street is not dominated by cars. It is a nice pedestrian street. (Note how the woman is walking right down the middle of the street.) The street width here is about the width of the two sidewalks alone in the San Francisco model. Actually, it is about the width of the area taken by the huge stairways alone — if you had one on either side of the street. Since we’re fronting a quiet pedestrian residential street, not an automobile-dominated street, we don’t need a buffer “transition zone” between the street and the house. (If you tried to put that huge stairway in front of a house on a street like this, it would look quite ridiculous.)

Try to imagine this street with the San Francisco houses, minus their Hypertrophic front stairs. (They could just have the entrance on street level, next to the garage for example.) They could even have little backyards — although high land values tend to make people think twice about their need for their very own little patch of grass. Just go to the neighborhood park.

Big beautiful townhouses like the ones in San Francisco would be unaffordable for most people. Their construction costs alone (not including land) would probably run $350,000+. Thus, they are a nice format for wealthy people, but an unrealistic aspiration for most. Most people could live in smaller houses, or apartments. Nothing wrong with that.

Another Jiyugaoka street. That’s a garage on the right there, and a couple more houses on the left.

Residential street in Gotanda district, Tokyo. Nice little townhouses, with cars. This street is about eight feet wide.

These are all examples of townhouse-type design with cars included. You can have a Really Narrow Street with cars, if you don’t use the cars too much. Commuting to work, local shopping, going to school etc. should be done without a car.

Eguisheim, Alsace again. This is a very small village in France. These are also townhouses, mostly. This is a typical format when people don’t have cars at all — and you don’t really need them, because they are way too much trouble just to use every other weekend. Just rent one!

Unlike the rather grandiose San Francisco townhouses, these are quite modest, and would be affordable for middle-class people without a lifetime of debt slavery. Still quite nice though, don’t you think?

You probably thought I was way too picky about the huge stairs in front of the San Francisco (or New York) townhouses. Heck, it’s just a little stair. Can you see now why I called it hypertrophic? The stairs on these houses (two steps) are about right. Those big San Francisco-type stairs, seven feet high and protruding seven feet into the street, are completely unnecessary in a proper pedestrian environment.

A village in China. These appear to be townhouses — personal residences. Maybe with a few small stores mixed in. This is a Traditional City no-car format. There’s no need for a buffer in front, in the form of a lawn and driveway, or a humungous stair, because there are no cars roaring away in front of the house.

Roadways, parking and Green Space. Ottawa, Canada.

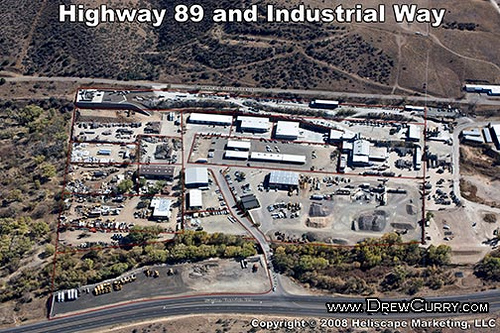

Big box shopping, commercial intersection, Suburban Hell. Target, Barnes and Noble.

Binghamton, New York.

Suburban Hell “Power Center.” First four stores from left to right: Wal Mart, TJ Maxx, Pet Depot, Grand China buffet. Binghamton, New York.

19th Century residential neighborhood. Binghamton, NY. Built before automobiles!

Almost identical to typical Suburban Hell development. Definitely NOT a Traditional City design.

Suburban Hell is “Small Town America” with more parking!

“Everything you need to know is in this picture.You either get it or you don’t.”

Other comments in this series:

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

January 10, 2010: We Could All Be Wizards

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

November 22, 2009: What Comes After Heroic Materialism?

November 15, 2009: Let’s Kick Around Carfree.com

November 8, 2009: The Future Stinks

October 18, 2009: Let’s Take Another Trip to Venice

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

September 28, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to Barcelona

September 20, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity 2: It’s All In Your Head

September 13, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around the “Sustainability” Types

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

January 25, 2009: How to Buy Gold on the Comex (scroll down)

January 4, 2009: Currency Management for Little Countries (scroll down)

December 28, 2008: Currencies are Causes, not Effects (scroll down)

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

December 2, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Tokyo

October 7, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Venice

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

July 9, 2007: No Growth Economics

March 26, 2006: The Eco-Metropolis