Today, we will continue our talk about NGDP Targeting, adding a third (and, I think, final) representation of the idea from one of its proponents. This is a paper entitled “Sound Money: An Austrian proposal for free banking, NGDP targets, and OMO reforms,” by Anthony Evans of the Adam Smith Institute. If you aren’t already laughing, you haven’t been paying attention through this series.

September 15, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting

September 22, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #2: The Classicals and the Mercantilists

September 29, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #3: What’s The Value?

October 6, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #4: A Pattern of Continuous Currency Decline

October 13, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #5: Sumner’s Take

This paper is particularly characteristic of the tendency to paint NGDP Targeting as a fundamentally Classical (that is, “hard money”) proposal, when it is really a Mercantilist (“soft money”) proposal, and not only that, a rather extreme one, in which any deviation from the NGDP Target is to be corrected via as much monetary distortion is necessary to achieve the goal. This “monetary distortion” amounts to a change in the value of the currency, presumably down when NGDP is undershooting and up when it is overshooting.

Adam Smith himself was a fan of the gold standard, as most everyone was in the latter 18th century. He certainly was not a fan of what I’ve called the “Mercantilist” approach, typified in that era by James Denham Steuart‘s An Inquiry Into The Principles of Political Economy of 1767. Some people think that Adam Smith’s famous work, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) was a direct response to Steuart. Here’s Wikipedia:

Although the work [Steuart’s Principles of Political Economy] appears to have been well received its impact was overshadowed by Smith’s Wealth of Nations that was published only nine years later. Adam Smith never quotes or mentions Steuart’s book, although he was acquainted with him. It has been argued that Smith avoided Steuart’s arguments because they would have undermined his Utopia. Moreover, the attacks on Mercantilism in the Wealth of Nations appear to have been mainly directed against Steuart.

So you have to admit that seeing an NGDP Targeting proposal, which I’ve characterized as “Mercantilist” quoting Steuart, from something called the Adam Smith Institute, is rather delicious. But, this is in line with the Cato Institute, Independent Institute, Mercatus Center and other supposedly free-market institutions that have actively embraced NGDP Targeting, which is Steuartism on steroids.

Here is some info on the author, from the paper:

The author, Dr Anthony Evans, is ideally suited to make such a challenge. Anthony is, without a doubt, one of the best of the up-and- coming generation of free market economists: a highly original and much regarded thinker with an remarkably wide range of interests including money and banking, political economy, managerial and cultural economics, and much else besides. He is a faculty member of the ESCP Europe Business School and a member of the Shadow Monetary Policy Committee run by the Institute of Economic Affairs.

The first part of the paper deals with Open Market Operations, and is in response to the very large amount of discount lending that was done in the 2008 crisis, as I mentioned earlier, as banks sought to build much larger cash (central bank deposit) reserves after running very close to zero for many years. This is a worthy discussion, and not a bad idea it seems to me.

This brings us to the more interesting second section, which is about NGDP Targeting. Again we have the reference to “Austrians,” in particular Friedrich Hayek, who we mentioned last week. Most “Austrians,” and especially Ludwig von Mises, were die-hard gold standard fans, but Hayek never was. This was a little odd considering that most of the world was on a gold standard during most of Hayek’s lifetime. I group Hayek along with other “monetary subversives” including Milton Friedman, who also talked a big talk regarding Libertarian economic principles, except for money, where he was adamantly in favor of floating currencies. Hayek was at least something like a commodity-basket targeting fan, which was about as far from the mainstream (gold standard) as you could get in the 1920s and 1930s without being considered a kook. But, by the postwar era, the process of intellectual decay — shall we just call it one form of Cultural Marxism? — had reached the point where Friedman would talk about freely floating currencies, and belittle the gold standard that was actually, at that time, producing rather good results worldwide, and roomfuls of conservatives would nod their heads up and down in admiration. The fact that, in the century prior to 1960, no country that had tried floating currencies (and there were many of them, even in the pre-1914 era) ever had any success, while the gold standard countries like the U.S. and Britain remained world leaders, apparently was not considered very relevant.

March 5, 2017: Floating Currencies of the Classical Gold Standard Era, 1850-1914

Friedman at the time was also promoting dopey “rules based” systems, in particular a Constitutional Amendment (!) that would require the monetary base to grow at some even pace around 4% per year.

March 6, 2014: Bitcoin Proves That Friedman’s Big Plan Was A Joke

This was “First Generation Monetarism.” It was idiocy. (There is some evidence that this “First Generation Monetarism” led directly to the blowup of the Bretton Woods System in 1971.) This led to “Second Generation Monetarism,” which was based on banking-system indicators like M2, which is basically base money plus bank deposits, and a few other things. This was the “Monetarist Experiment” of the early 1980s, and it too was a short-lived disaster. Maybe the third time is the charm (I doubt it) for the Monetarists. NGDP Targeting has also been called “market monetarism.” The idea behind Monetarism 1.0 was that steady base money growth would lead to steady economic growth (NGDP). This was also roughly the premise behind Monetarism 2.0. So, it is no surprise that today’s Monetarism 3.0 basically just uses NGDP as a target, with the idea of supplying whatever amount of money is necessary to hit that target.

The paper does have some nice quotes from Hayek. Apparently these are from separate sources in the 1970s.

I agree with Milton Friedman that once the Crash had occurred, the Federal Reserve System pursued a silly deflationary policy. I am not only against inflation but I am also against deflation. So, once again, a badly programmed monetary policy prolonged the depression.

The moment there is any sign that the total income stream may actually shrink [during a post-bust deflationary crash], I should certainly not only try everything in my power to prevent it from dwindling, but I should announce beforehand that I would do so in the event the problem arose.

If I were responsible for the monetary policy of a country I would certainly try to prevent a threatening deflation, that is, an absolute decrease in the stream of incomes, by all suitable means, and would announce that I intended to do so. This alone would probably be sufficient to prevent a degeneration of the recession into a long- lasting depression.

The paper then goes into a longish discussion about what the “correct” NGDP Target is. Apparently there is some disagreement about this. As I have been saying, the NGDP target will seem fine until it is actually used in the real world. Then, something will happen — probably, something unpleasant happens to currency values (exchange rates) and interest rates — and it will be clear that something needs to be done to fix the problem. All of a sudden, the supposedly “automatic rules-based” NGDP target becomes a whole lot more discretionary. And how are we going to decide? Maybe we can have a board of twelve governors meet every six weeks.

The paper goes on and on about the “equation of exchange.” I find this a little funny considering that there are some estimates that 70% of all dollar banknotes are outside the United States. Also, foreign banks hold about 30% of all bank reserves at the Federal Reserve. There is a pretty big international dollar-based banking system (“eurodollars”), not to mention a pretty big market worldwide in dollar-denominated debt throughout the emerging markets. The dollar is used as the invoicing currency in about 40% of all international trade, about 75% of which is between two countries neither of which uses the dollar as a domestic currency. So, relating any measure of “money” (base money or global dollar M2) to U.S. domestic NGDP is more than a little silly. It is the typical “closed economy” fantasy popular among academics who don’t get out much.

In the end, the paper, like the others we’ve seen, goes on and on about P and Y but there is nothing about the value of the currency. The second section ends with a somewhat bizarre discussion in which the “Austrian” proposal is an NGDP target of 0%! That is, an unchanging nominal level of GDP. This comes from some dumb ideas that Hayek had in the 1930s. I don’t think that Japan, which had NGDP growth of 17% per year in the 1960s, with a gold standard currency of unchanging value, would be too happy with 0% instead. This is the silliest of silly fantasy. (On the other hand, maybe 0% would have been the right number to avoid currency decline in the 2001-2011 period.) The author concludes that maybe we could just take the average of 0% (“Austrian”) and 5% (proposed by the “market monetarist” group) and end up with 2%. He does characterize a common NGDP target among “market monetarists” as 5%, which is what we saw earlier with David Beckworth. This would presumably have caused the dollar, which fell from $280/oz. of gold in 2001 to $1900/oz. in 2011, to fall even further to meet the NGDP targets. This apparently does not seem to bother anyone; they don’t even seem to imagine that it is an issue. Maybe if we ignore the question of currency value completely, we will end up with “Sound Money”?

This comment was good:

As Alex Salter has said, “stable nominal spending is not the cause of economic prosperity, it is the consequence of the same institutions that provide prosperity”.103 In other words a healthy economy might exhibit stable NGDP, but stable NGDP will not necessarily create a healthy economy. (p 45-46)

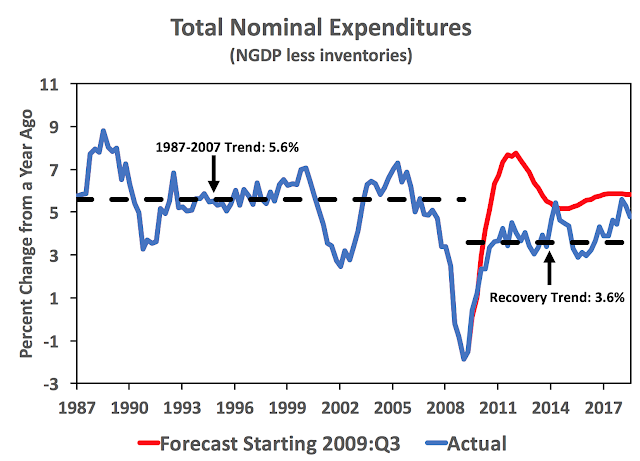

We saw that, during the “Greenspan gold standard” era when the dollar’s value was roughly (sometimes, very roughly) held around $350/oz., economic growth was pretty good. After 2002, NGDP held about the same pace even though the dollar’s value had a big fall against gold (and also, I think, in real terms). Then NGDP was even more depressed after 2009.

In other words, Low Taxes and Stable Money (roughly speaking) produced pretty good results during the “Greenspan gold standard” period. But, replicating this NGDP level with currency decline, as happened after 2002, did not produce good results. It is really Kennedy and Nixon all over again.

November 18, 2018: JFK Vs. Nixon = Gold Vs. NGDP Targeting

This has been characteristic of Monetarism in general. The fact that the monetary base grew at an average of X% during a prosperous gold standard era, does not mean that you achieve the same prosperity or monetary conditions by increasing the monetary base by a certain percentage each year (first generation Monetarism). The same holds true of measures of M2 (second-generation Monetarism), and also, I would say, measures of NGDP (third generation Monetarism). All Monetarism basically accomplishes its goals (if they are accomplished at all) via changes in currency value, which is obviously not the same as Stable Money; or, more broadly, Low Taxes and Stable Money.

The paper ends with some talk about “free banking.” It is a little unclear what is being proposed here, so I skipped to the Appendix, which is a concrete policy for the introduction of “free banking” in Britain in the middle of a proposed crisis situation, where I was surprised to find the very first mention of gold:

Permanently freeze the current monetary base

Allow private banks to issue their own notes (similar to commercial

paper)Mandate that banks allow depositors to opt into 100% reserve

accounts free of chargeMandate that banks offering fractional-reserve accounts make

public key informationGovernment sells all gold reserves and allows banks to issue notes

backed by gold (or any other commodity)Government rescinds all taxes on the use of gold as a medium of

exchangeRepeal legal tender laws so people can choose which currencies to

accept as paymentThe Bank of England ceases its open-market operations and no

longer finances government debtThe Bank of England is privatised (it may well remain as a central

clearing house)

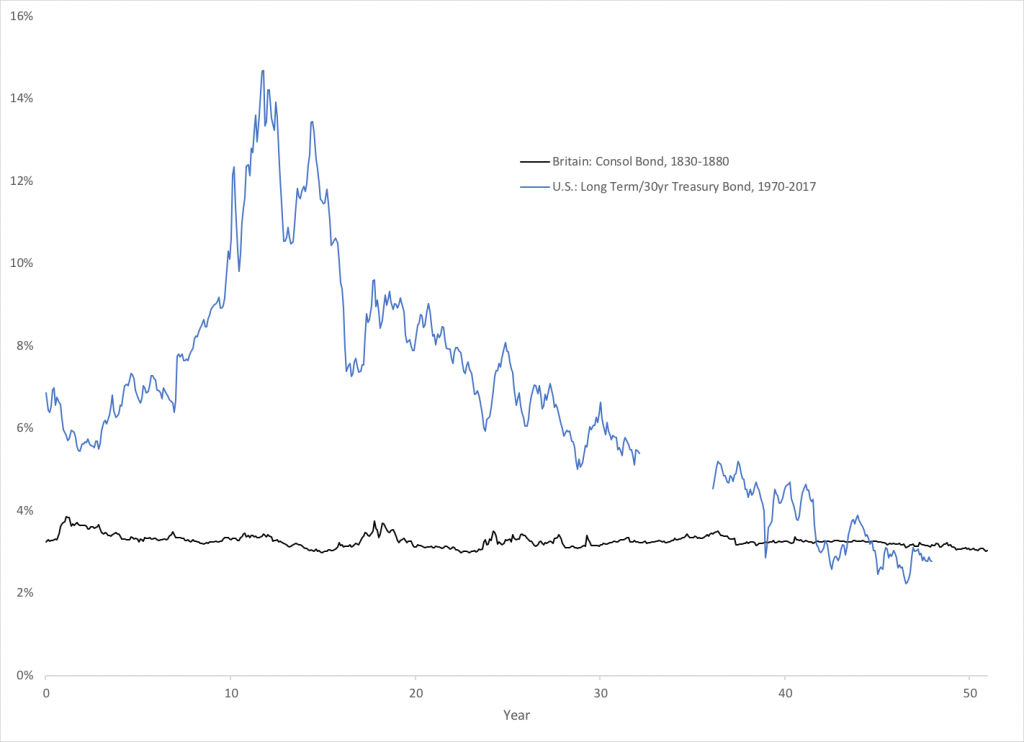

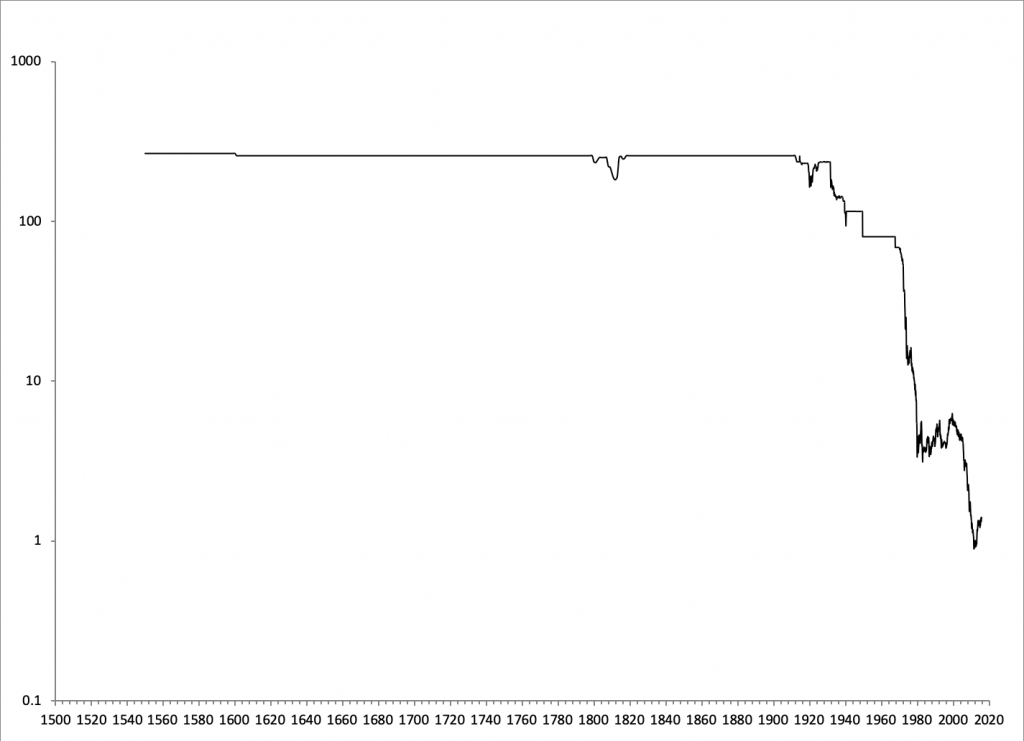

And so, after discussing everything except the gold standard, we find that, in this scenario, Britain returns to the monetary principle that made the British pound one of the most reliable currencies in the world since the first silver pennies were minted by King Offa of Mercia in the late eighth century.

That is a little schizophrenic. But, I actually find that it somehow describes where we are today. There seems to be the idea that we will return to the gold standard, but only after a crisis. In the meantime, we will coast along with Business As Usual, which seems to include babbling about NGDP Targeting as the latest in a long string of money-manipulation proposals stretching over the last hundred years, and which still have not produced any evidence that they are better than Britain’s wonderful gold-linked pound in the nineteenth. For as long as we are still on the PhD Standard, the PhDs are going to go through the motions.

December 7, 2016: The Gold Standard Vs. The PhD Standard

I thought about writing a final conclusion piece to this series on NGDP Targeting, but perhaps there isn’t much to be gained by beating this dead horse any longer. In The Magic Formula, I summarized currency outcomes in three simple categories:

1) The currency generally rises in value, over time. This is recessionary and favored by nobody, except perhaps as a remedy to prior devaluation, such as in 1865-1879 for the U.S. dollar.

2) The currency goes up and down in some erratic fashion, and ends up about where it began. This was the case during the “Greenspan gold standard” years, for example (if you squint a bit to make it look better). This might have some proponents, who might argue that you could have a weak currency during a recession and then make it up later, but in general, it would be better simply to have a stable fixed-rate system such as a gold standard or perhaps a euro or dollar standard (for emerging markets), rather than have all the uncertainty and trauma of floating currencies and end up where you began.

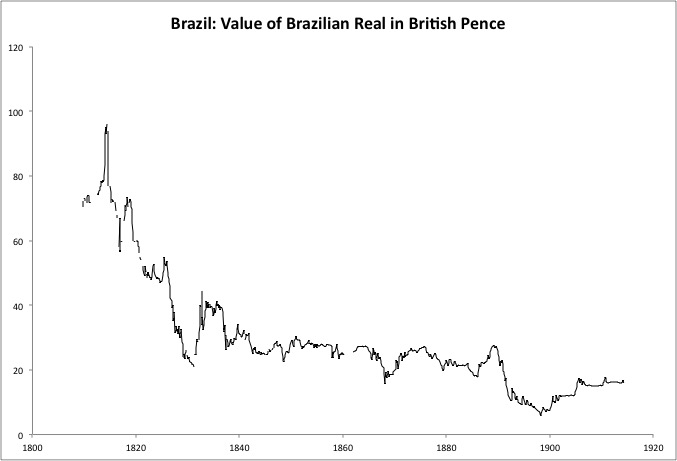

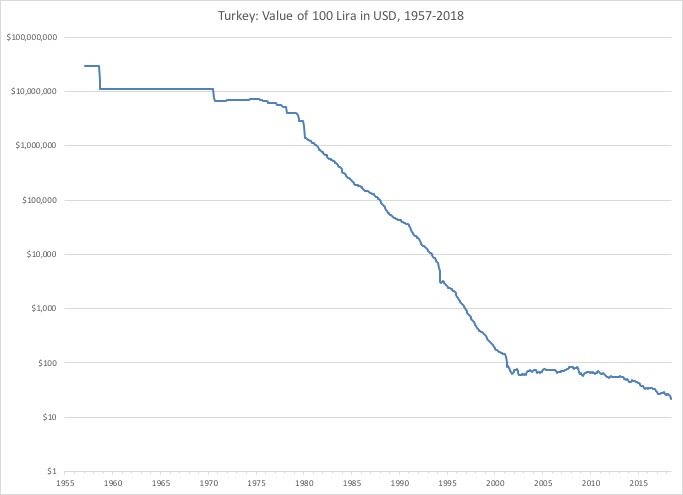

3) The currency has a long-term tendency to decline in value. This is the outcome of various “easy money” solutions to deal with all problems, and has always had many proponents. By the 18th century, the French franc was worth about one-hundredth of its original value under Pepin the Short and his son, Charlemagne. Today, it wouldn’t take a thousand years to produce that outcome. The dollar today is worth about 1/40th of its value in 1970, vs. gold., and about 1/4th of its value in 1995.

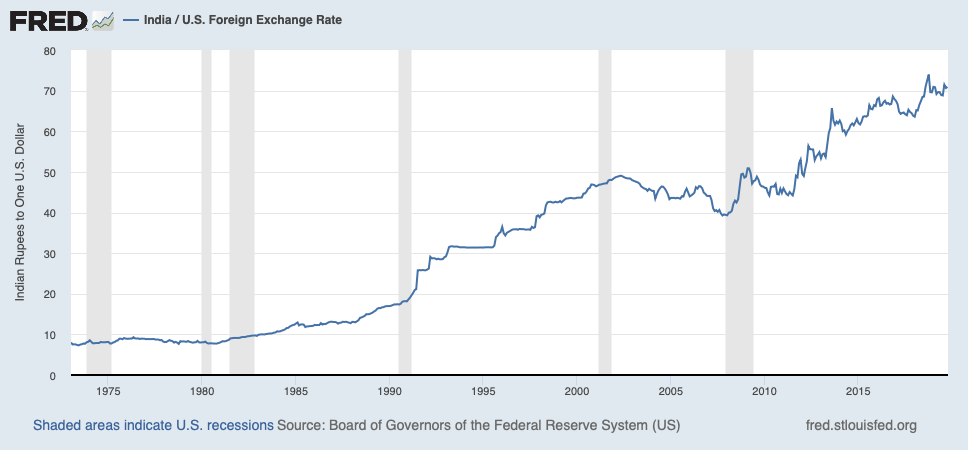

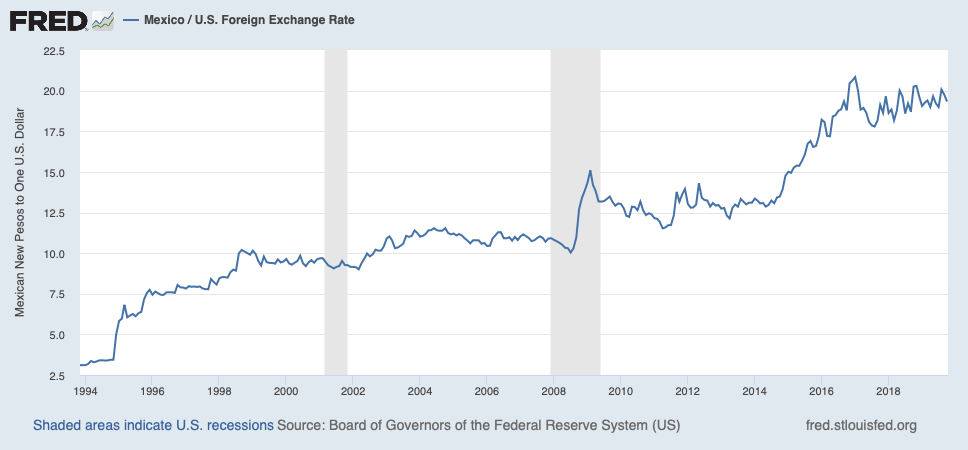

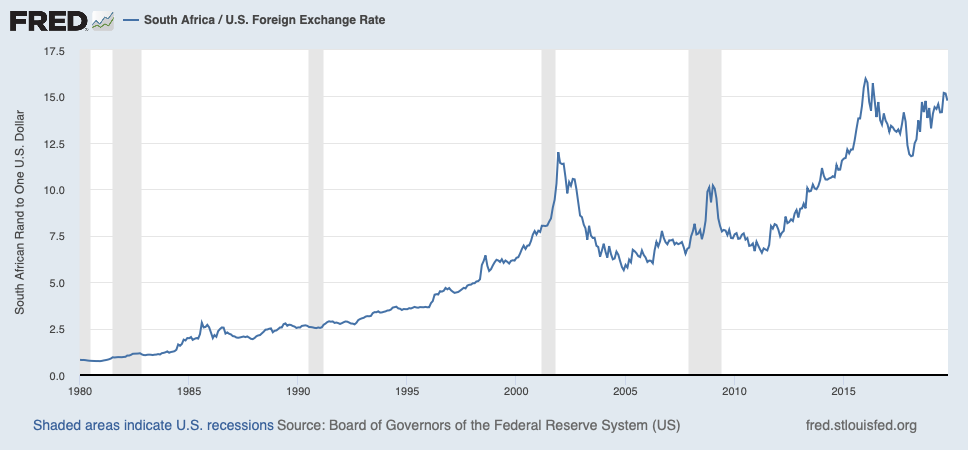

Basically, NGDP Targeting amounts to changing the value of the currency to hit the NGDP Target. For the period since 2001, I think it is clear that the common targets for NGDP, proposed by NGDP Targeting fans, are around 5% — this figure arrived at even with all the 20/20 hindsight offered by history. Since this is well above the actual result, and that actual result itself came about with considerable currency depreciation (to about $1500/oz. gold today from a plateau around $350/oz. in the 1990s), it seems clear to me that this implies even more currency depreciation than what actually took place. So, NGDP Targeting, in actual practice, would probably look a lot like Situation #3: a continuous long-term trend of currency depreciation. You can look at countries that have actually exhibited a long-term trend of this sort, over the past two centuries, and none of them have been very successful at it.

Is that really the club you want to be part of?

Or would it be better to imitate Britain, while the British Empire was at its peak, while Britain was the leader of the developed world, while Britain had the highest per-capita GDP in the world, while Britain was the world’s financial capital and the British pound was the world’s premier currency?

Shouldn’t we imitate winners not losers?

In any case, after all this yammering about “P and Y,” the NGDP Targeting people seem to have nothing to say about currency value, even though that is effectively the mechanism through which their system operates. They have nothing to say about consequences for exchange rates, and from this, trade or interest rates (look at the domestic interest rates in Turkey), or how it is supposed to work on an international level when about 40 countries link the value of their currencies to the dollar. You could even say that it was NGDP Targeting which led to the blowup in 1971.

November 18, 2016: JFK Vs. Nixon = Gold Vs. NGDP Targeting

But, it seems that people understand that, at some level. Even Anthony Evans, supposedly an NGDP Targeting fan, seems ready to throw it overboard if the chance arose to get what he really wants: a gold standard system, for Britain, as it once was, and should always be.