Let’s Visit an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 26, 2009

We’re not done with our American Village yet.

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

This is part of our series on villages:

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

So far, we’ve defined some of the attributes of 19th Century Hypertrophism as expressed in a small town dating from 1800. They are:

1) Rather excessively wide streets, contrary to the format of the Traditional City of the previous 4000 years, even though this was a century before automobiles and there was no utilitarian need for oversized roadways.

2) Residential buildings which follow a rural format, of a freestanding farmhouse surrounded by a lawn, rather than an urban format of a townhouse or apartment. This is identical to today’s suburbs, and in fact is less dense than most suburbs today.

3) Commercial buildings (stores/offices/industrial) which follow a Traditional City format, multistory and side-by-side, but which are combined with the excessively wide streets.

4) The overall effect is an environment that is unfriendly to pedestrians and favorable to automobiles, although the pattern dates from a century before automobiles.

The changes that turned the 19th Century Hypertrophism of Small Town America into Suburban Hell are:

1) Even wider streets to accomodate more automobile traffic.

2) The addition of parking lots in commercial areas, and a general trend toward further hypertrophism in commercial areas.

3) The addition of enormous amounts of useless “green space” to provide a buffer between people and the huge automobile-filled roadways/parking lots.

4) Zoning, which was in some ways an attempt to separate the residential areas (still largely identical to the 19th century format) from the stinking horror that the commercial areas/huge roadways/giant parking lots had become.

So we see that Suburban Hell doesn’t really differ from Small Town America by very much. The main difference is bigger roads and parking lots — concessions to the automobile. And then, lots of “green space” and zoning to try to put all the automobile crap as far away as possible from people’s houses. These concessions to the automobile were desired because the Small Town America format is inherently flawed. It is not the pedestrian no-car environment of the Traditional City. Thus, you can’t “fix” Suburban Hell by making it more like Small Town America, because Suburban Hell itself is an attempt to “fix” Small Town America by making it easier to drive in.

I say that we should fix Small Town America’s inherent flaws by making it easier to walk in, which is to say, adopt the Traditional City format.

That the roadways of 19th Century Hypertrophism are exceedingly wide, but that is only in relation to pedestrian use and the Traditional City format. In relation to the automobile, they are barely sufficient. Thus, the desire to make things even wider. The two-laner became the four-laner with dedicated left-turn lanes. In this way, the not-very-walkable 19th Century Hypertrophic City became the totally unwalkable Suburban Hell. “Unwalkable” means that everyone has to drive, which means more traffic, which means bigger roadways and more parking, and more “green space” to try to counteract the roaring ugliness of six lanes of traffic, and more zoning and bigger yards (if you can afford one) to try to put the whole catastrophe as far away as possible. You know how the story goes. You live in it!

Thus, you can’t fix Suburban Hell by adding a train, because, to make a long story short, you can’t walk to the train, and you can’t walk from the train to where you want to go. The typical Suburban Hell approach to a train station is to surround it with an endless desert of Free Parking, which is exactly, precisely the opposite of what you want to do. Then, because nobody wants acres of burning asphalt, we mix in an equal amount of Green Space, which makes it even harder to walk to and from the train station.

Let’s continue our tour of New Berlin. Last week, we made it to the main intersection. Now we will take a right turn, away from Main Street and onto some secondary streets.

Now we’ve turned the corner at the main intersection. The supermarket is on the right. This is where I make another comment on the super-hugeness of the street, compared to the Traditional City format. Also, I note again that it is quite easy to take a picture of a gorgeous building in New Berlin, but once the roadway enters the picture … kind of an aesthetic bummer, no? Note that in a photo of a Traditional City, you can take a picture of the middle of the road, and it is quite pleasant.

Napoli, Italy

Nothing wrong with taking a picture of this street. It is perfectly photogenic. Note that the width of this street, from building to building, is about the width of a sidewalk in the 19th Century Hypertrophic model. (The 20th Century Hypertrophic model doesn’t have sidewalks.)

See what I mean? The sidewalk (including Green Space) is about the same as the entire street width in the Traditional City.

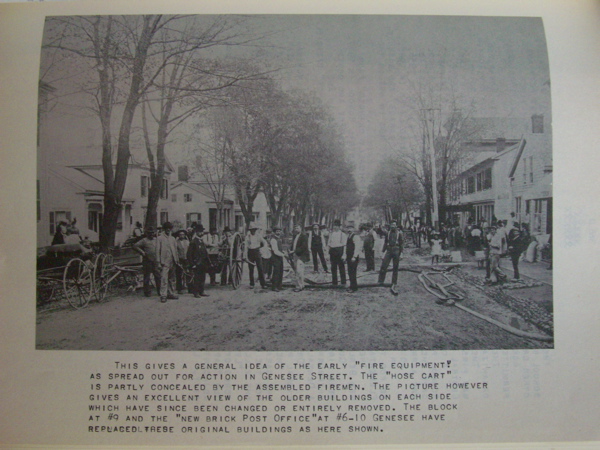

Here is the same street, around 1900 or so. Here we have the whole volunteer fire department standing in the middle of the street, and it comes nowhere near to filling up that immense space.

Another gorgeous house. Big, too.

Of course there’s a carriage house.

This is a little later house, from about 1900 or so. By this point, people had adopted central, hydronic heating (water-filled radiators). At first, they were coal-fired.

You know what this is.

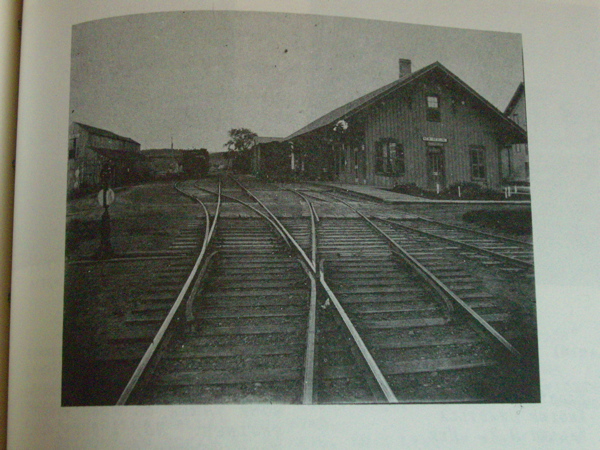

This was the old depot, or warehouse for the train. The train ran behind this building. Yes, even a dinky town like this had a train, and you could ride it all the way to New York City and beyond if you wanted to.

The train station.

This is where the tracks used to be.

Is that really a pipe to reload the water for the steam engines?

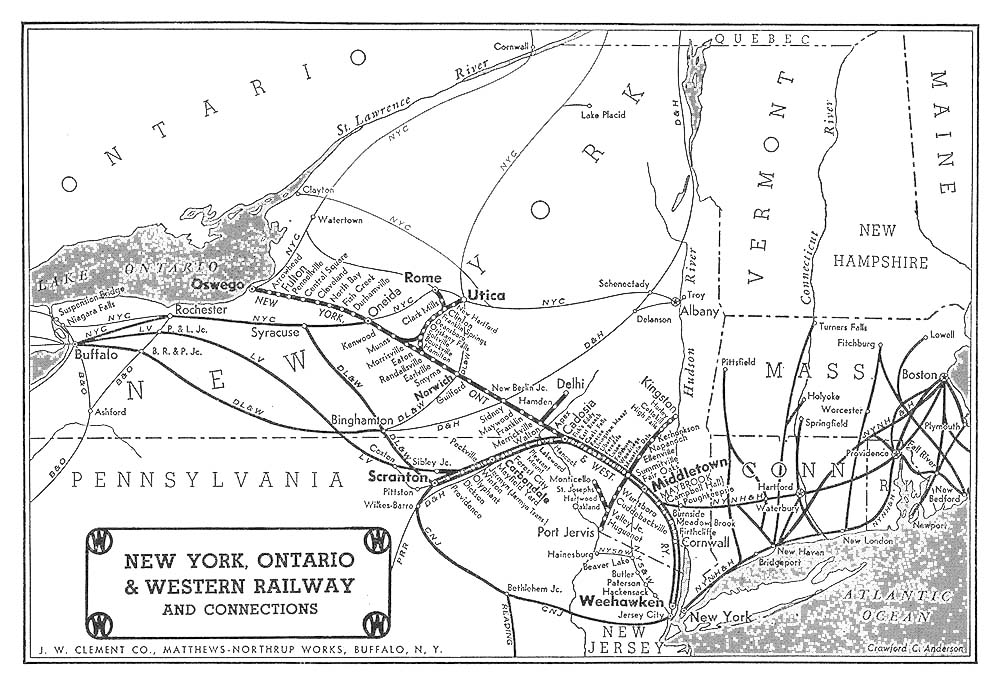

History of the New York, Ontario and Western Railway

Now we’ve made another right turn, onto a back street (Green Street). Once again, I note that this format is identical to today’s suburbs. This is plainly not the Really Narrow Street of the Traditional City (or Traditional Village).

Chinese village.

This is an old-style Chinese village house. Instead of a “yard,” they had a sort of open courtyard. Quite majestic.

Chinese village. Where are the CARS?

Note that even the Chinese didn’t walk around in the mud. The street is nicely paved with flagstones.

Swiss village. This street is plenty wide if you aren’t trying to drive here.

Note how the Swiss village and the Chinese village look rather similar. This is:

1) a wild coincidence.

2) because it works.

Central square of a village in Switzerland.

Gruyere, Switzerland.

This is back side of the Preferred Mutual office building. We saw the original office building on Main Street. The company expanded its office building, and of course, it provided parking to its employees. This is the only large parking lot in the town — a Suburban Hell format laid upon the old 19th Century Hypertrophic Small Town format. A number of old houses were torn down for this parking lot. We see also the emergence of “green space.” Because, who wants a featureless expanse of blacktop stuffed with machinery? So, there’s plenty of landscaping around to make things a little less horrible. (And then they added the chainlink fence to make things a little more horrible.) Of course, this means that even more land is consumed in the parking of cars, which lowers density still further, and makes it that much more impossible to walk around, thus increasing people’s dependence on cars. In this case, since there is only one such parking lot, the town has been able to deal with it without too much disruption.

A closer look at the parking lot. Office blocks and parking lots! This is not on the outskirts of town, either: it’s in the very middle of town. You could fit about half the village of Eguisheim, Alsace in this parking lot.

This woman decided to have something besides grass in her yard. Nice!

Nice Greek Revival.

One of the old factories. Note that this factory has no parking space! People walked to work in those days.

This carriage house is so big, it was converted into an apartment building.

Another intersection. We make a right turn.

The back of the Preferred Manor. Not a whole lot of “urban density” here. Like I said, the Small Town America format is less dense than typical suburbs. This is probably one reason people fantasize about Small Town America — there’s lots of open land. In the Suburban format, more land = more wealth. So, a place with lots of land around the houses says: “upper class.” Or, in other words, the more money you have, in Suburban Hell, the more you try to imitate this Small Town America arrangement.

The Preferred Manor is still a gorgeous building. You just can’t make a city out of this pattern.

The carriage house at the Preferred Manor.

Guest House next to the Preferred Manor, and its carriage house.

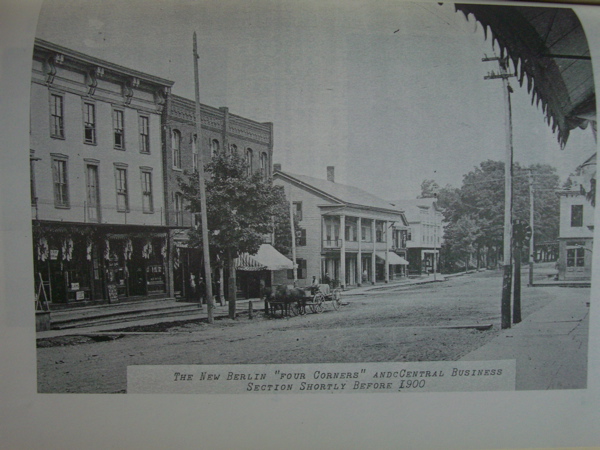

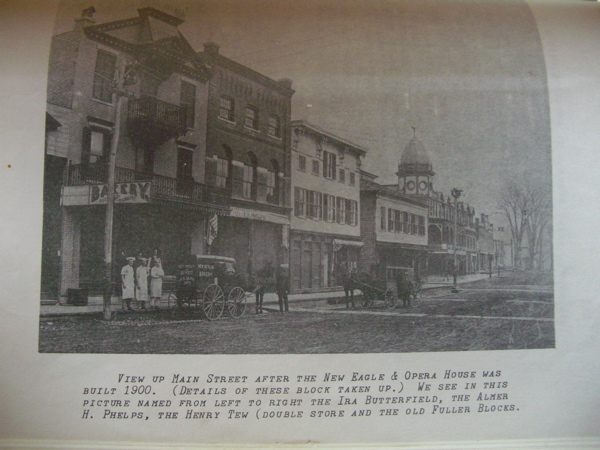

What it looked like before cars. Note once again the complete lack of justification for the huge expanse of dirt. One wagon! Nice Traditional City-style buildings though.

Yes, the town had an Opera House. They didn’t have TV in those days.

This is an intersection in the neighboring town of Norwich. Once again we see the lovely Traditional City-style buildings. However, the roadway is now expanded far beyond New Berlin size. Including the space for parking, we now have SIX lanes of traffic! Plus some pretty big sidewalks on either side. The sidewalks alone would make a perfectly good street in a No Car Traditional City.

What were they thinking?

Here we have a shot of just one sidewalk, to show what I mean. Look at the width. I’d guess that’s about ten feet wide. This town was actually laid out before New Berlin. The Town of Norwich was established in 1793. The population today is about 7,000 people.

Later on, we will complain some more about the super-wide roadways of Suburban Hell. But, actually, they are not that much wider than this roadway of the late 18th century. It was an American thing from way back. The main difference today is Lots of Parking and Green Space.

Lisbon, Portugal.

I’d say this is about seven feet wide.

Note that there isn’t a “traffic jam” or something like that. This is completely sufficient.

Lovely Lisbon commercial street. Note that people are NOT walking around in the mud.

This is pretty wide by Traditional City standards. As we can see, it is nowhere near crowded, although this is not a small town or village, it is a major European capitol. You could march a column twenty people wide down here with no difficulty whatsoever.

The streets in Norwich are twice as wide. You can see the consequences, particularly after the automobiles arrived.

One thing you’ll notice in the Traditional City is that there is no separation between the “street” and the “sidewalk.” The whole street is designed to be used by a pedestrian, although if there is an occasional delivery truck that is OK too. If you look at the old pictures of New Berlin, you’ll see the early development of sidewalks. It appears that people got tired of walking in the mud, so they paved (or, more commonly, boarded over) some sidewalks on either side. This, of course, split the street into a “section for walkers” and a “section for wagons,” which was unpaved.

Lisbon street. This is about the width of the two sidewalks in Norwich alone. But, it is still plenty wide enough for the occasional wagon or delivery truck. By Traditional City pedestrian standards, it is more than ample enough for a LOT of people to walk around in.

This is the cross street in Norwich. Once again, a nice building and a Hypertrophic street.

I mentioned that the Small Town America format, or 19th Century Hypertrophism, is not too bad IF the size is below 5,000 people. Even though I’ve been pointing out the considerable design flaws of New Berlin, nevertheless the place still has a certain charm. And, you can get around by walking, even if it is quite a bit more strenuous than would be the case in a Traditional Village. However, in Norwich we can see that the automobile traffic has already become quite oppressive, and things are getting spread out to the point where we would rather drive than walk. Which kinda sucks, but I bet it sucked even more before people had cars.

“Honey, don’t you think we should get a carriage?”

Most Americans don’t like big cities. Here we can begin to see why — from a very early stage, they adopted a Hypertrophic format which doesn’t scale. The bigger it gets, the worse it gets. Times ten once cars arrived. This is the opposite of the Traditional City format. The bigger the Traditional City gets, the better it gets!

Woo hoo!

(Nobody in this picture is dreaming of a little farmhouse in the woods.)

Today’s suburbs are like the small towns of the mid-19th century in more ways than just their appearances. Henry David Thoreau retreated to a little cottage by Walden Pond in 1846:

When I consider my neighbors, the farmers of Concord, who are at least as well off as the other classes, I find that for the most part they have been toiling twenty, thirty, or forty years, that they may become the real owners of their farms, which commonly they have inherited with encumbrances, or else bought with hired money — and we may regard one third of that toil as the cost of their houses — but commonly they have not paid for them yet. It is true, the encumbrances sometimes outweigh the value of the farm, so that the farm itself becomes one great encumbrance, and still a man is found to inherit it, being well acquainted with it, as he says. On applying to the assessors, I am surprised to learn that they cannot at once name a dozen in the town who own their farms free and clear. If you would know the history of these homesteads, inquire at the bank where they are mortgaged. The man who has actually paid for his farm with labor on it is so rare that every neighbor can point to him. I doubt if there are three such men in Concord. What has been said of the merchants, that a very large majority, even ninety-seven in a hundred, are sure to fail, is equally true of the farmers. With regard to the merchants, however, one of them says pertinently that a great part of their failures are not genuine pecuniary failures, but merely failures to fulfil their engagements, because it is inconvenient; that is, it is the moral character that breaks down. But this puts an infinitely worse face on the matter, and suggests, beside, that probably not even the other three succeed in saving their souls, but are perchance bankrupt in a worse sense than they who fail honestly. Bankruptcy and repudiation are the springboards from which much of our civilization vaults and turns its somersets, but the savage stands on the unelastic plank of famine. Yet the Middlesex Cattle Show goes off here with éclat annually, as if all the joints of the agricultural machine were suent.

We have been appreciating the spectacular big houses of the mid-19th century, many of which would cost $500,000 or more to build today, if you could even find craftspeople capable of doing so. Were they really so wealthy? It appears that bankrupting yourself for a house far larger and more extravagant than anybody needs is as American as apple pie.

“We were mortgaged up to our eyeballs just like you.”

* * *

This series of photos is of empty commercial real estate in Florida, but it is about the best “photo essay” of Suburban Hell that you’ll find. People take umpteen bazillion photos of Venice, but it’s actually hard to find good (i.e., appropriately horrible) photos of Suburban Hell. Why would anyone take a picture of it? We are in denial about the pigsty we’ve built for ourself.

Even the Ferrari dealer looks pretty crappy if you ask me.

Photo essay on Suburban Hell, Florida-style

Other commentary in this series:

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

January 25, 2009: How to Buy Gold on the Comex (scroll down)

January 4, 2009: Currency Management for Little Countries (scroll down)

December 28, 2008: Currencies are Causes, not Effects (scroll down)

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

December 2, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Tokyo

October 7, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Venice

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

July 9, 2007: No Growth Economics

March 26, 2006: The Eco-Metropolis