In the past, I’ve written about “Life Without Cars.” This time, I think we will have a little change of tone: “Life After Cars.” People get the tremblies at the idea of “without.” But, we seem to sense that the Automobile Age is passing. Nobody likes it. It’s time for something new. But, we haven’t come up with a clear alternative yet.

December 28, 2014: Life Without Cars 2014

December 8, 2013: Life Without Cars: 2013 Edition

December 27, 2012: Life Without Cars: 2012 Edition

December 25, 2011: Life Without Cars: 2011 Edition

December 19, 2010: Life Without Cars: 2010 Edition

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

Click Here for the Traditional City/Heroic Materialism Archive

I make two propositions:

1) That most people living in cities should not own a car, or use one regularly. This means that transportation is accomplished on foot, or by train, bicycle, bus, or taxi, in roughly that descending order of preference. This is already common in many large cities worldwide, in both the developed and developing worlds. Walking is the primary mode of transportation. For most people, it is all they need for their most common trips to work, shopping, school, or to the local train station. When a train, bicycle or bus is used, it is to travel from one walking-centric place to another walking-centric place.

We’ve been fooling around with cars for a hundred years, without one single example of success. Yet, we have a profusion of great urban places for people walking. It is not hard at all. Humans have a long history of accomplishments in this realm.

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

August 1, 2010: The Problem With Bicycles

2) That cities should be designed to be beautiful, pleasant, convenient, comfortable and affordable, for people who do not own cars. Obviously, once you accept the first premise, the second naturally follows. I should mention that “people” doesn’t just mean childless people mostly between the ages of 16 and 35. It includes babies, small children, elderly, mothers, fathers and families, and also young women, who have a lower tolerance for ugliness than men. But, Americans especially have a lot of difficulty here. The American experience, from 1789 onwards, tends to divide into two things:

Low-density automobile-dependent suburbs (and previously, small towns centered on farming); or

19th Century Hypertrophic Cities (New York, Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo, etc. etc.) that were not beautiful, not pleasant (especially in the days of coal soot and bad sanitation), not comfortable and, especially today, not affordable.

When you put it into words like that, it probably seems impossibly Utopian. But, actually humans have a long history of success in doing exactly this. For example:

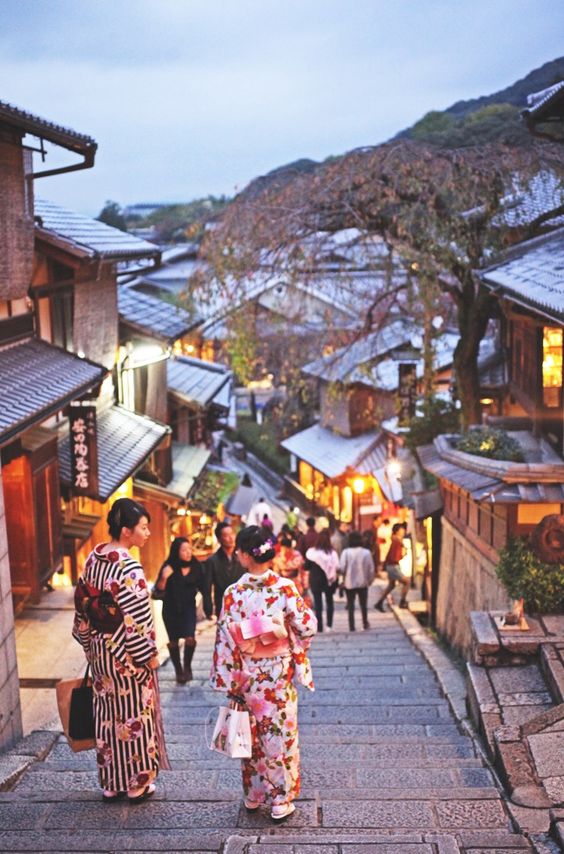

Kyoto, Japan.

Quebec City, Canada

Cordoba, Spain

Warsaw, Poland

By “cars” I mean personal automobiles. We can still have motor vehicles, since nobody wants to go back to oxcarts. These are trucks, buses, vans and taxis — essentially, commercial vehicles. You can rent a car, or perhaps use some future self-driving taxi. The self-driving taxi promises to allow “Life Without Parking” and also “Life Without Owning a Car,” both of which hold considerable promise, especially given how much land area is taken by parking and related Green Space buffers. Obviously, the self-driving car is an easier bolt-on to the U.S.’s present automobile-dependent land-use patterns. However, I don’t think this holds as much promise as the city based on trains. We would end up with much the same dysfunction — anyway, much the same traffic. Try to imagine if New York, London or Paris tried to replace its train and subway system with self-driving cars. I’ve never seen any solution better than a well-developed train network, such as is common in Germany, China or Japan; and indeed, it is hard to even think of a problem that one might aspire to remedy.

Things have moved on a lot since I first started on this topic around 2007. The ideas that were radically new at that time (although embodied in centuries of human experience in building cities) have become more broadly embraced, to the point that enough people share them — there is enough consensus — that we have begun to see some real-life implementation. People have come to recognize that many cities today are grotesquely inhumane. This is true of what I call Suburban Hell, but also of the 20th Century Hypertrophic City (which is basically the automobile suburbs with highrise architecture), and also of the 19th Century Hypertrophic City, typified by New York or Chicago. With that in mind, I want to comment a bit on where we stand today.

The goal is to make Places for People. Obviously, if you do not make a Place for People, then you are making … something else … which is probably not going to be as good. You are probably not even realizing that you are not making Places for People, but the consequences will be just as bad nevertheless. So, make Places for People.

I propose that Places for People take on three basic forms:

2) Parks and Squares

3) Private space, including commercial and residential buildings (building footprint, indoor space), and also small outside areas associated with these, such as gardens, backyards, courtyards, patios, sports fields, etc.

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

First, these areas are Places. They have a name, which typically includes some recognition of their identifiable form. They have a purpose, and that purpose includes the enjoyment of the space by People. For example, a residence might have a Yard or a Garden, with an identifiable purpose such as recreation, beauty or growing vegetables, and a form which is expertly designed for that task.

I think there are some real attempts today to break out of the bad habits of yesteryear, and to make something that is better. Sometimes this is successful; and when it is successful, I find that it is because the result mimics existing and proven Traditional City forms. If is not successful, I find that the failure can be described using the tools above. There is some kind of vaguely vegetated outdoor space that is not identifiably a Park, Garden, Sports Field or the like; some kind of street-like form that is not identifiably a Street, but perhaps is a mushy combination of Street and Square; some kind of open paved area that is not identifiably a Square. Without a name or identifiable form, they typically do not have an identifiable purpose. Children play in parks. But, if some place is not identifiably a Park, should you play there? Probably not.

October 11, 2015: Parks and Squares 4: Smaller Squares

August 16, 2015: Parks and Squares 3: Squares

August 2, 2015: Parks and Squares 2: Smaller and Closer

July 26, 2015: Parks and Squares

April 12, 2015: Narrow Streets for People 4: Organizing the Street

March 22, 2015: Narrow Streets for People 3: A Shopping Center Example

March 15, 2015: Narrow Streets for People 2: Subtleties of Street Width

March 8, 2015: Narrow Streets for People

For example, here is a promising development in Boulder, Colorado. It includes this Narrow Street for People-like space:

But, the project also includes this funny space:

Is this a park?

It could be a park. It vaguely resembles a park. It is not identifiably something other than a park. But, I would say that it is NOT a park — meaning that not even the designers had the idea that they were making a “park,” or identified this space with a name that includes the word “park”, or that I would call it a “park” or can identify it conclusively as a “park” — and it would not be used as a park. Probably, like many such confused, low-value and semi-useless spaces today, it would become a favorite destination for skateboarders. If it is a “park,” then it could certainly be a much better one. Even in this rendering, it seems to be abandoned by the cyber-people, who apparently would rather stroll, chat and ride their bikes on the sidewalk. Designers: back to work! This time, Make A Park. Make it the best park you can.

Here is a project in West Hollywood, CA. This section (which appears to be a few stories off the ground) is called “Havenhurst Park.” I would say it is identifiably a park. It could be better — and will be, when the trees get a chance to mature — but I give it a thumbs-up.

I find that Streets can be segregated into three types: the Narrow Street for People, the Arterial, and the Grand Boulevard. They have different purposes, and thus different forms. Perhaps the most difficult idea is that perhaps 80% of all the streets in a city, by length, can or should be Narrow Streets for People. The idea of an “alley” here or there, perhaps under 5% of total street length, that is a sort of pleasant commerical place, is not too challenging for most people. But, 80% of all streets? Actually, this is not only quite common worldwide, but works well for vehicles as well. Despite the Narrow Street for People being the most common street form, typically no building is more than a quarter-mile (1300 feet) or so from an Arterial. Obviously, it is not so easy to change existing street patterns. But, often developers are working with a blank slate, either a greenfield development or some sort of urban redevelopment, and they have to define street forms, parks and squares anyway, so they might as well do a good job of it rather than a bad one. Also, there are a lot of opportunities to create “streets” in private spaces such as shopping centers, resorts or townhouse developments, which are not necessarily municipal rights-of-way.

Failure to make attractive Street forms typically involves the confusion and admixture of these categories. For example, the Narrow Street for People can become quite problematic when it is too wide, as is common when people are influenced by “Main Street USA” ideas based on the Arterial form. It becomes a forbidding blank barren space, even at widths of forty feet or so, and which practically begs to be broken up with planters, benches and other whatnot. It is better simply to make the street narrower, perhaps twenty feet; or, perhaps, to create a Square. The Arterial, on the other hand, can benefit from being wider, and adding things such as trees or dedicated bicycle lanes, which can easily take the width up to eighty feet or more. While the Narrow Street for People form is best when there is no street segregation — it is one flat plane from side to side — the Arterial form should be segregated into a central lane dedicated to vehicular use, and sidewalks for pedestrians, and perhaps even more segregation for dedicated bicycle or BRT lanes. There should also be some kind of buffer between the two, and a row of trees has been one of the most successful solutions. The Grand Boulevard can be very large, and designed for high-speed crosstown traffic; but there shouldn’t be very many Grand Boulevards. The typical U.S. 19th century hypertrophic city has basically one street form — the Arterial — as even the Grand Boulevard is commonly replaced by an intracity freeway.

April 13, 2014: Arterial Streets and Grand Boulevards

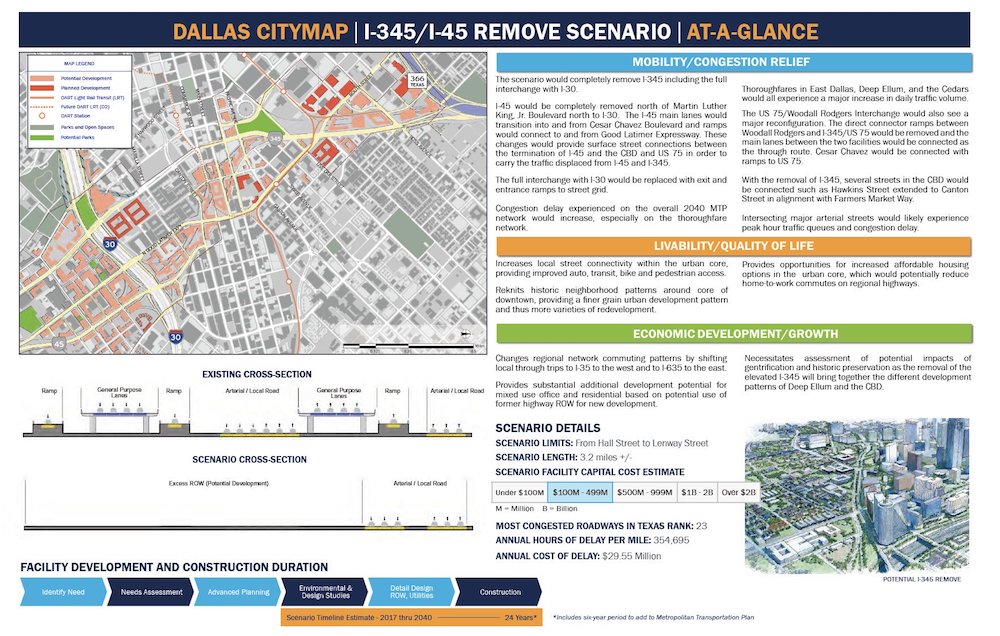

Example of “laneway” street form, City of Toronto municipal planning department. (Includes a bicycle and truck making a delivery.)

Example of “Civic Street” (Arterial) street form, City of Toronto municipal planning department.

The Traditional City form, with buildings rarely taller than six stories, is easily capable of densities of 55,000 (the City of Paris) or even 100,000 people per square mile. “Sububrbs” of single-family detached residential buildings in Japan, typically of three stories or less, commonly achieve densities of 30,000 people per square mile, which is nearly as high as Brooklyn (37,000/sqmi). So, there is really not much need to use highrise architecture. Instead of “building out” (expanding further into greenfield) or “building up”(highrise), quite a lot can be accomplished by densifying with buildings of six stories or less. If the City of Oakland, CA, the eastern suburb of San Francisco (7,400/sqmi), had the density of the City of Paris (55,000), it could be home to 3.1 million people, instead of 419,000. That is just the City of Oakland, not the entire East Bay. It is 3.5 times the population of the City of San Francisco (864,000), and a pretty large part of the entire San Francisco metro area most broadly defined, with a population of 8.7 million. And not a single highrise. There is never really any great shortage of land, and housing prices, ex-land, are basically a function of construction costs. Construction costs for high-quality masonry or steelframe construction are about $200/sf, so you can do the math — a 1000sf apartment would cost about $250,000 to build (including common areas like hallways), for construction alone. Any “shortages of affordable housing,” in any metro area, are largely a fuction of artificial land scarcity (developable land is being kept off the market somehow) and also barriers to construction (via zoning or any number of other local regulations and legal hurdles). We can see this in Tokyo, for example, which has always had high land costs, but where “affordable” market-rate housing is highly abundant. The “free market” should have no problem creating low-cost solutions for housing at a market rate, just as it provides low-cost solutions for virtually every other thing under the sun — and in many cities, especially in Asia where people haven’t yet tied themselves up in knots, it does.

September 26, 2016: The $50,000 San Francisco Home

July 31, 2011: How To Make a Pile of Dough With the Traditional City 5: The New New Suburbanism

July 17, 2011: How To Make A Pile of Dough With the Traditional City 4: More SFDR/SFAR Solutions

June 12, 2011: How to Make a Pile of Dough with the Traditional City 3: Single Family Detached in the Traditional City Style

Paris of the present … potential Oakland of the future.

This section of Beirut, Lebanon, was destroyed in war and rebuilt after 1990.

Realistically, a city is a big thing, and it will take many decades to change its form. But, we have done this in the past: cities were not always automobile suburbs. Cities are always changing form. The only difference is to change it for the better; that new construction be an improvement. The amount of money, or percentage of GDP, spent each year on construction is not likely to change very much. So, we don’t have to spend any additional money. The amount already being spent — which, in the U.S., is trillions of dollars — is already enough. We just have to spend the same money, and get something better.

May 23, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City

June 6, 2010: Transitioning to the Traditional City 2: Pooh-poohing the Naysayers

August 22, 2010: How to Make a Pile of Dough with the Traditional City

Since both developers and municipal planners/government agencies both want to make something better while spending the same amount of money (in principle), the only real obstacle is figuring out what that “something better” is. In other words, the ability to imagine a successful solution. If even 5% of a city’s surface area was in the form of the Traditional City, that would radically change its character. For example, we imagined what it could be like if the City of Oakland were remade in the Traditional City form of the City of Paris. Nice idea, right? Now, what if just 5% of Oakland were in the form of Paris? That would be 5% of 55.8 square miles of land, or 2.79 square miles — 1,786 acres. That would be perceived as a huge area. 153,000 people could live there, at the average density of 55,000/sqmi in Paris. Some of Paris’ residential arrondisements have population densities in excess of 100,000 per square mile. So, if this 5% of Oakland was built out as a residential area in that pattern, 279,000 people could live there. So you see, we don’t really have to change everything, all at once. Just 5% would be huge. Just 2% would be major.

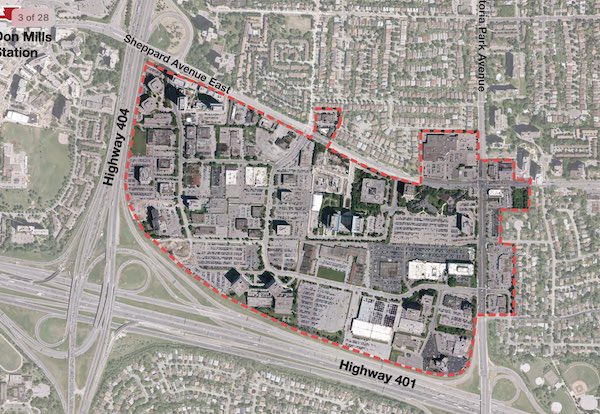

Large section of Toronto suburbs, to be redeveloped including new street pattern.

So you see, I am not just fantasizing. Major municipal goverments are already planning to rebuild large sections of their cities in a better form. So the only question is: how do we get a great result?

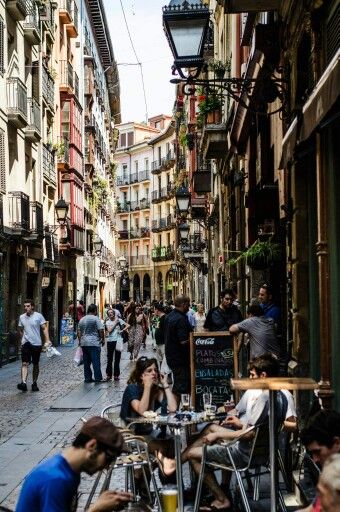

Narrow Street for People, about twenty feet wide and no central roadway/sidewalk segregation. The basic building block of the Traditional City form.

Boston, MA.

Melbourne, Australia.

Devon, England.

Portland, Maine.

Bilbao, Spain.

What if 80% of all the streets in your city looked like these examples?

We have begun to see a few examples of the successful combination of Traditional City elements — Narrow Streets for People, Parks and Squares — with highrise buildings. For many reasons, a highrise solution might be best for a particular development, so the question is: how to make it better? We used some basic Traditional City ideas to make big improvements in the design of the Hudson Yards development in western Manhattan, which includes 90-story buildings.

February 28, 2016: Let’s Take A Look At Hudson Yards

I talked about combining highrise with Traditional City forms in this series:

September 23, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau 3: Really Narrow Streets With High-Rises

August 26, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau 2: More Place and Less Non-Place

August 19, 2012: Corbusier Nouveau

Here is a new highrise development in Gothenburg, Sweden. These four pics are all from the same development.

This is pretty much your Paris-style Narrow Street for People with 4-6 story buildings … and some towers off “in the back somewhere.”

Higher up, a Patio — an identifiable Place for People.

Whoa! This is a serious highrise! Soooo much different than the “tower in a park” form that I call 20th Century Hypertrophism.

Here is a development in Qingdao, China.

This highrise project in Brooklyn, New York includes parks and patios for People. It would be better, I think, if there was a bump-out at ground level (pedestal form) with more of a Traditional City height of two to six stories.

Among all of the advantages of the Traditional City based on walking and trains, is the fact that they are very environmentally friendly. The environmental advantages that one can achieve from living in this manner are so great, that it is almost a waste of time to consider alternatives that don’t include Traditional City living. You simply aren’t going to get there by sprinkling windmills, solar panels, goats and tomato plants on the U.S. automobile suburb. Farmers should live on farms; but most everyone else should live in cities, whether small rural villages or giant metropolises.

May 8, 2014: Environmentalism is the Key to Growth

April 10, 2014: How to Make Billions While Making People Happy and Saving the Planet

March 2, 2014: The Eco-Technic Civilization

April 4, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms 2: How Many Acres Can Sustain a Family?

March 28, 2010: The Problem With Little Teeny Farms

March 14, 2010: The Traditional City: Bringing It All Together

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around the “Sustainability” Types

In our Life After Cars, we will still have cars, but we won’t need them. Our cities will be designed for People, not Cars. All the building blocks are at our hands and ready to use. We don’t need any new technology. If anything, yakking about Smart-This-Or-That is a distraction from the real challenge of making a street and a park that is a place you want to live. If you can imagine it, then soon hundreds of billions of dollars will be directed towards its construction, for the simple reason that it produces a better result than spending the same hundreds of billions on something else — the Suburban Hell, 19th Century Hypertrophism and 20th century Hypertrophism forms that we all hate.

This is already starting to happen.

Click Here for the Traditional City/Heroic Materialism Archive