Today, we will add to our look into monetary policy in the 1960s, and a tendency toward deterioration that culminated in the effective abandonment of the Bretton Woods world gold standard system in 1971. Before, we looked at some statistical data, such as interest rates and open market gold prices. Now, we will take a more historical approach.

“Money Printing” in the 1960s Series

In particular, we will start with this paper from the Richmond Fed:

1965: The Year the Fed and LBJ Clashed

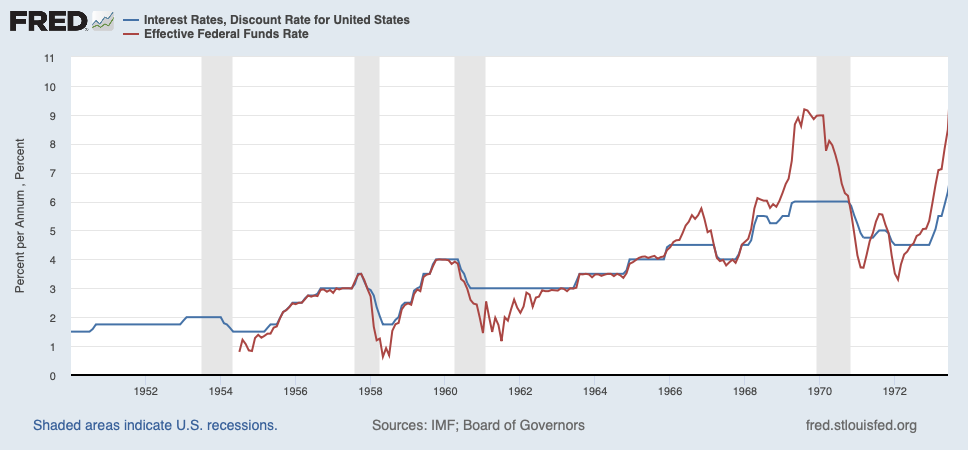

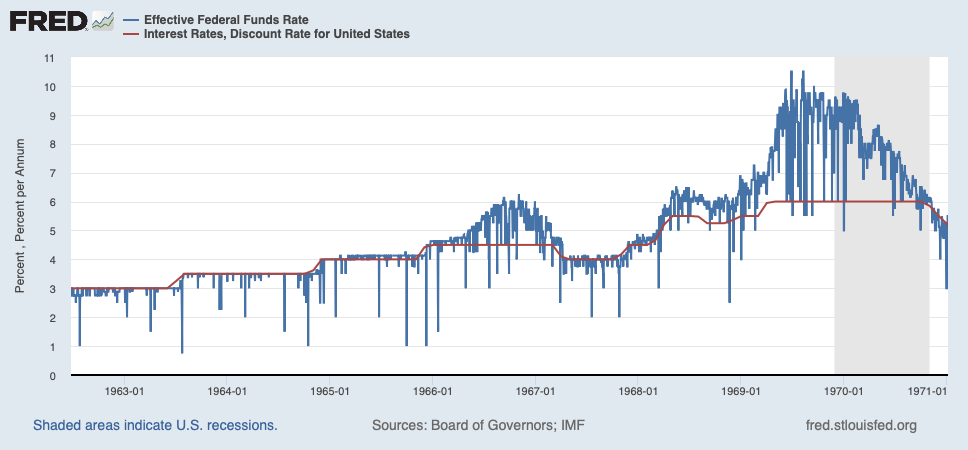

The first thing I learned, from the paper, was that the Federal Reserve’s primary interest rate tool in those days was the Discount Rate. The Federal Funds Rate (the rate at which banks lend to each other) did not take precedence until the 1980s. In effect, if the interbank lending rate was below the Discount Rate, then the Fed would be inactive. If it was above, then banks would go to the Fed to borrow. This produced an effective ceiling, but not a floor, on overnight interest rates, which is what we see at that time. It also means that Discount Lending was continuously active, while it was inactive during the 1990s and later.

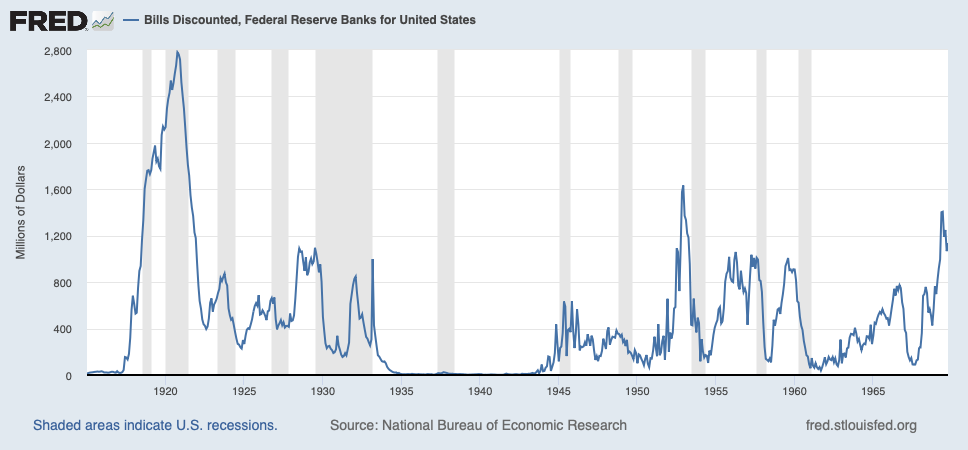

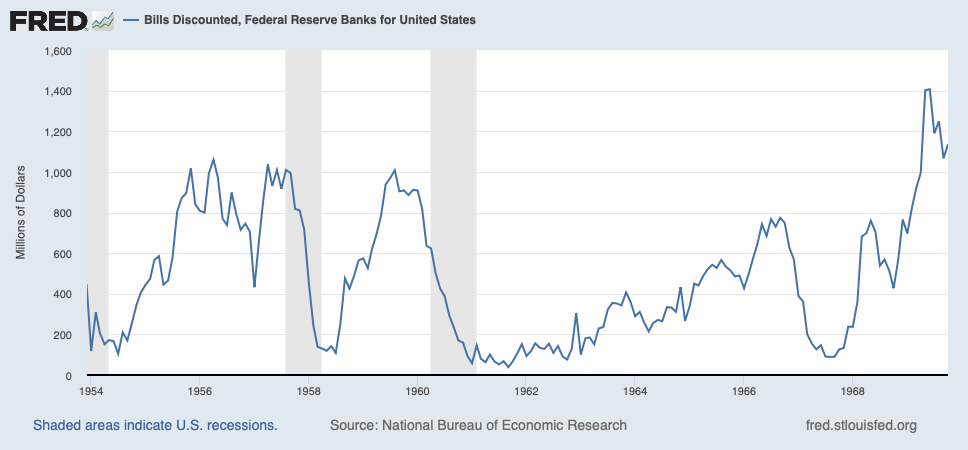

This graph shows the quantity of bills discounted, indicating that discount lending was highly active.

Here is the discount rate and the Fed Funds Rate. Obviously, there is a discrepancy beginning around the end of 1965 — exactly the time of the argument between Martin and Johnson described in the article.

This included a notorious episode where Johnson physically bullied Martin, pushing him up against a wall at his Texas ranch.

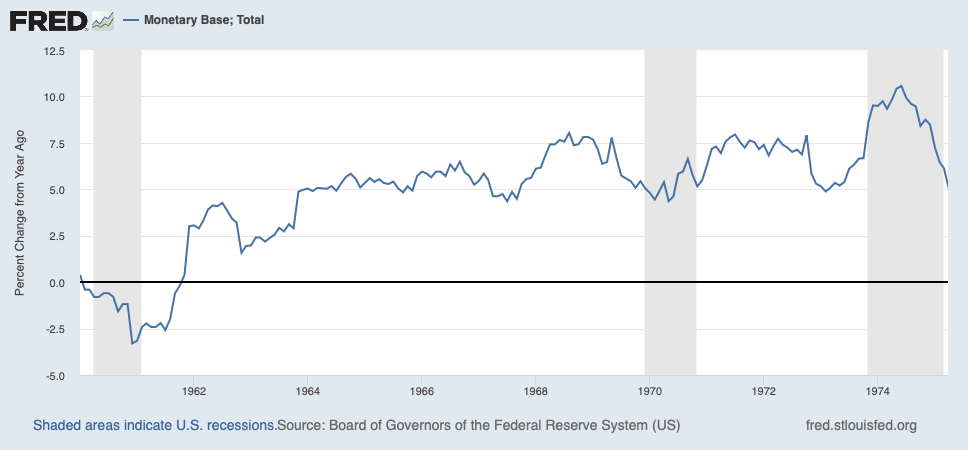

The Richmond Fed article mentioned that the Fed — following the Monetarist principles of Milton Friedman — was increasingly looking to base money growth rates as a policy indicator. The article says that a formal growth target was not adopted, but it looks like it was very close to that to me.

The Fed spent a decade waffling between a 5% and 7% growth rate for the monetary base. The episodes of a stronger dollar, in 1967 and 1970, correspond nicely to reductions in this growth rate; the weak-dollar episodes, in 1966 and 1968, correspond to expansions. I don’t think the relatively small change in the monetary base growth figures were too important in themselves, as Monetarists might claim. We are not dealing with steam engines here. Rather, I think that markets took a relatively “dovish” (7%-ish) or “hawkish” (5%-ish or below) stance to be an indicator of whether the Fed was favoring supporting the dollar and its official link to gold at $35/oz., or giving in to political pressures for “easy money,” which eventually led to devaluation. In other words, it was a political indicator.

This is, I think, a big reason why economists are always talking about “inflationary expectations,” or, in other words, WrongThink. They think inflation comes from thinking about inflation. Inflationary WrongThink. And, they are right, in a sense. If the market perceives that the Fed is going soft, then it will react in a way that can be much more exaggerated than the difference suggested by a 5% or 7% growth rate in the monetary base. In terms of a floating fiat currency, the increase in the monetary base by an additional 2% (7% instead of 5%) does not lead to a 2% decline in the forex value of the dollar. It might lead to a 50% decline, if there is a “loss of confidence” in the central bank’s ability or willingness to maintain currency value. This was, in fact, what really happened: markets overwhelmed the London Gold Pool in 1968 and the value of the dollar fell to $43/oz. of gold — a 19% decline, not 2%. WrongThink. Later, in 1973, the value of the dollar fell to $180/oz. of gold, while the growth rate of the monetary base was the same old 7%.

This tendency toward using a monetary base growth rate target, evident at the beginning of 1964, also coincided soon afterwards with the loosening of the interest rate target, including the deviation of the Fed Funds Rate from the Discount Rate in 1966. Basically, the Fed refused to lend any more at the official discount rate. It had become selective. Thus, the Discount Rate no longer served as a hard ceiling.

In his history of the Federal Reserve, Allan Meltzer recalls the drift of the Fed toward Monetarist ideals, citing this memo written by Martin sometime in 1965:

Monetary policy should not, and in fact cannot, be focused solely on interest rate objectives–any more than it can ignore them completely.

The immediate goal of monetary policy should be to provide the reserves needed to support a rate of growth in bank credit and money which will foster stable economic growth. It must take into account the international position of the dollar … It must be constantly concerned for the full employment of both human and physical resources. It must take into account price developments and the possibility of inflation, or the widespread expectation of inflation, which would do great damage to healthy growth. …

All these things, and many others, must be constantly weighed and balanced by the Open Market Committee. … We cannot produce through monetary policy alone, high or low interest rates, balance of payments surpluses or deficits, rising or falling prices, more or less employment, or a sound or unsound financial structure. We do exert some influence on all these things, hopefully in the right direction. (Vol. II, p. 480)

This is interesting beyond the expression of Monetarist principles in the first paragraph. These are still the early days of central bank funny-money rationalization. They didn’t even have floating fiat currencies yet. Yet, there is a definite tendency, which today has become all the more pronounced, of central banks wanting to meddle in every conceivable thing, while also absolving themselves of responsibility for anything. This whole business of the Open Market Committee having to take this, that and the other into account, of Guiding the Economy with their Great Brains and Wonderful Judgement, is apparently intoxicating to central bankers, despite the very clear track record of failure to achieve anything worthwhile by it. (The governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, wrote a book about that: The End of Alchemy.)The fact of the matter was: the Federal Reserve certainly could produce “balance of payments surpluses or deficits” (in practice, inflows and outflows of gold dependent on the value of the dollar compared to its gold parity), a stable currency that leads to low interest rates, and a sound “international position of the dollar” just as Germany and Japan were doing effectively at that time.

In other words, the Federal Reserve could have just maintained the dollar’s parity with gold, as the Bank of England did before 1913, and not worry about all the other macroeconomic tomfoolery. The result, just as the BoE experienced, would have been low and stable interest rates, probably around 3% for the 10yr Treasury bond. If they had not raised taxes in 1967-68, and with reliable Stable Money instead of the breakdown of the London Gold Pool in 1968, the economy would have continued booming just as it was in 1965, which would bring down unemployment. This is basically what Japan was doing at the time, and unemployment in Japan was never above 1.6%.

I think that, in addition to concern about interest rates, Johnson directly pressured Martin to absorb more of his big deficits by stepping up the Fed’s bond-buying. I think the Federal Reserve even had an official program of “fiscal accommodation.” It would be nice to add that at some point, if it comes up. But, perhaps we’ve had enough detail for now. It is enough to say that the Fed went along with Johnson’s easy-money inclinations, within a framework that was increasingly Monetarist (that is, targeting a stable growth rate of base money supply).