Here at Heritage, we have an article: “Inflation: Who’s Really At Fault?“

Since Heritage basically consists of followers of Milton Friedman, of course we get that “reckless money printing causes inflation.”

This is true. Reckless money creation (we don’t really “print” it anymore but it is still a nice metaphor) does cause “inflation.”

But, how can you tell if money creation is “reckless”?

Because it causes inflation, duh.

Money has to come from somewhere. It has to be created.

Also, the need for money (technically the “demand for money”) tends to grow as the economy grows. The US base money supply (notes and coins) grew about 160x between 1775 and 1900. One hundred and sixty times more money was in existence. Was this “reckless”? There was no inflation during that time. The value of the dollar was almost the same in 1900 as in 1775.

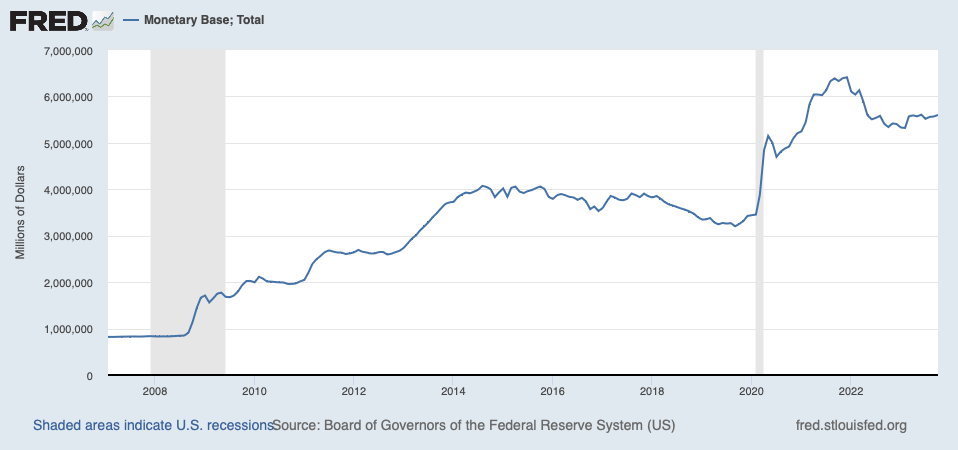

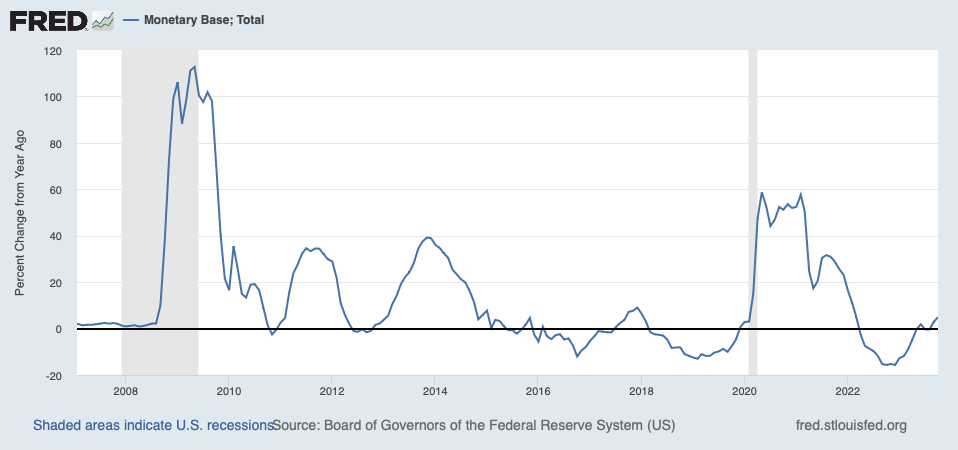

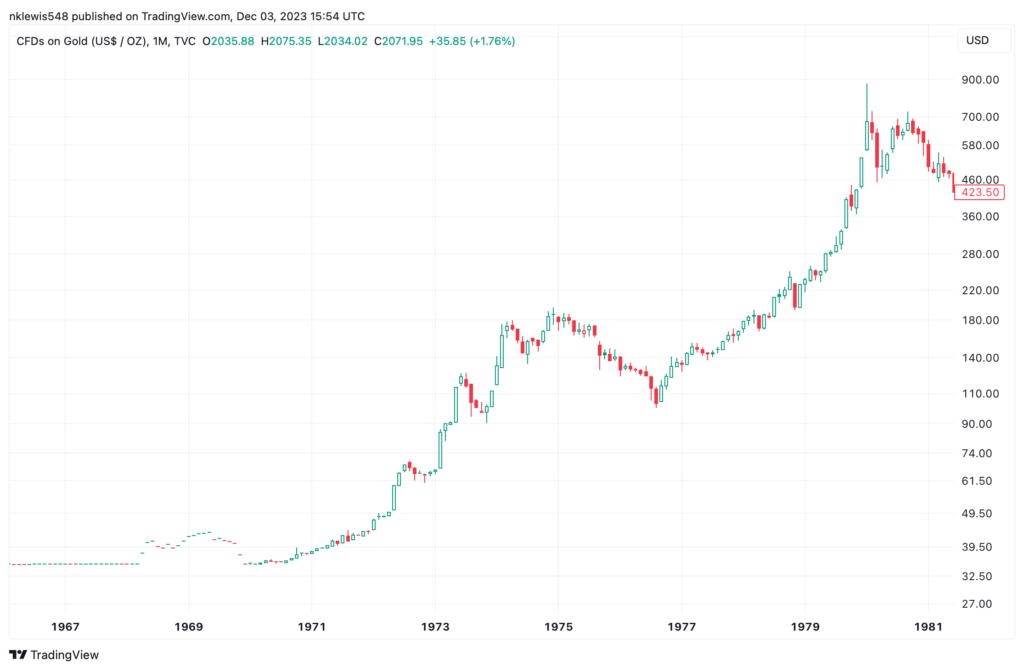

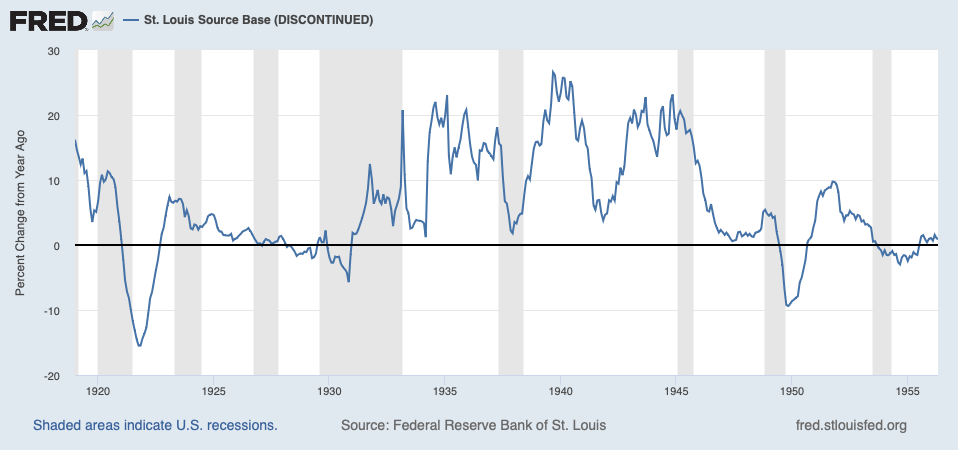

Let’s look at the pace of monetary base expansion (“money printing”) in recent years:

As we all know, there has been a lot of monetary base expansion not only recently, but since the financial crisis in 2008.

In 2008, the monetary base more than doubled. Was this “reckless”?

Some people thought it was. Seems obvious, don’t you think?

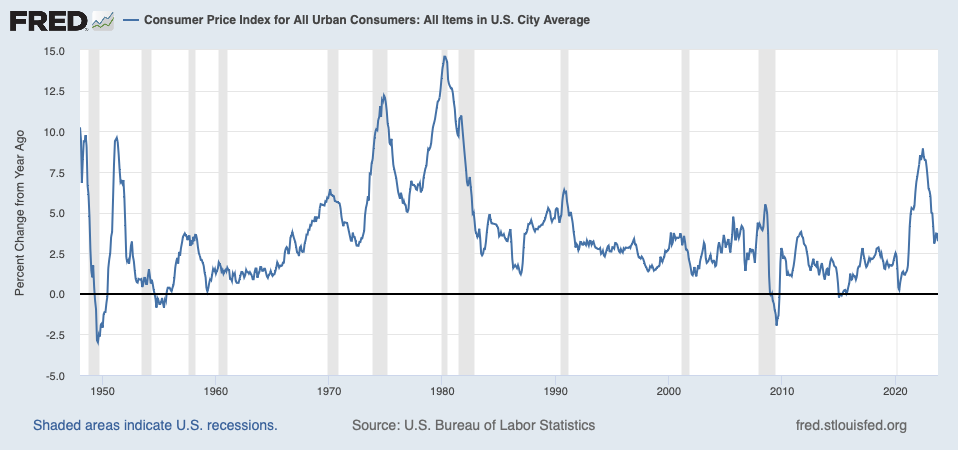

But, the outcome of that was the CPI “inflation” was among the lowest of recent decades. The Federal Reserve, not very long ago, was actually complaining that “inflation” was falling short of its 2% target!

We talked a lot about how a major change in banking practice, in Basel III, resulted in a need for banks to hold much higher levels of bank reserves at central banks.

In essence, the big increase in supply was mostly absorbed by banks, which had increased demand. The match was not perfect, but that’s the broad story.

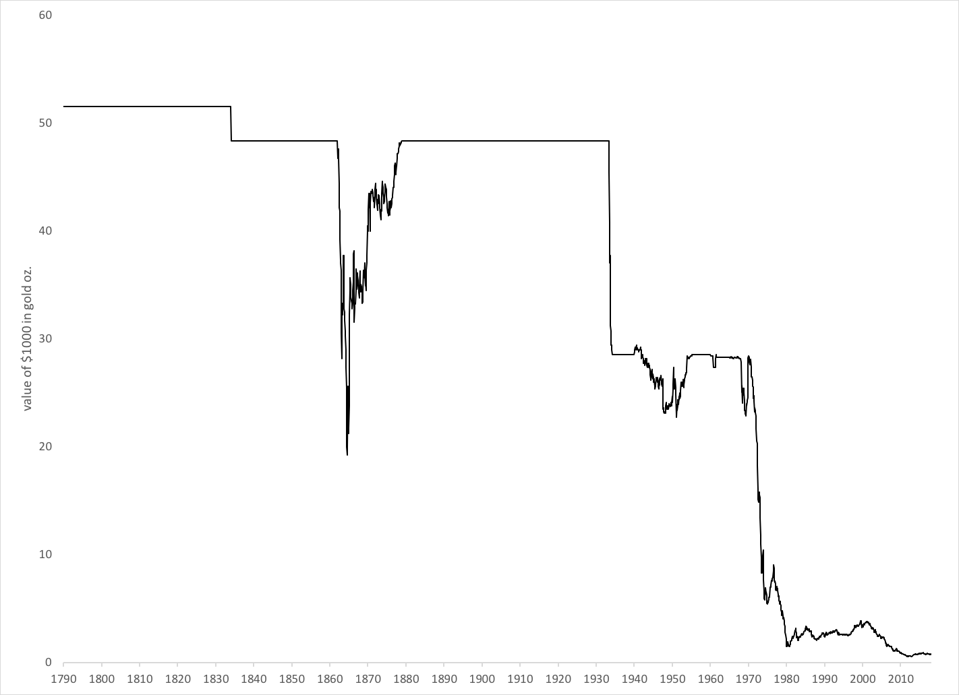

Compared to gold, the dollar fell somewhat during this time, but not nearly as much as might be implied by the very large increase in base money supply. Gold/USD hit $1000/oz. before the 2008 crisis, and was around $1200/oz. a decade later, in 2018.

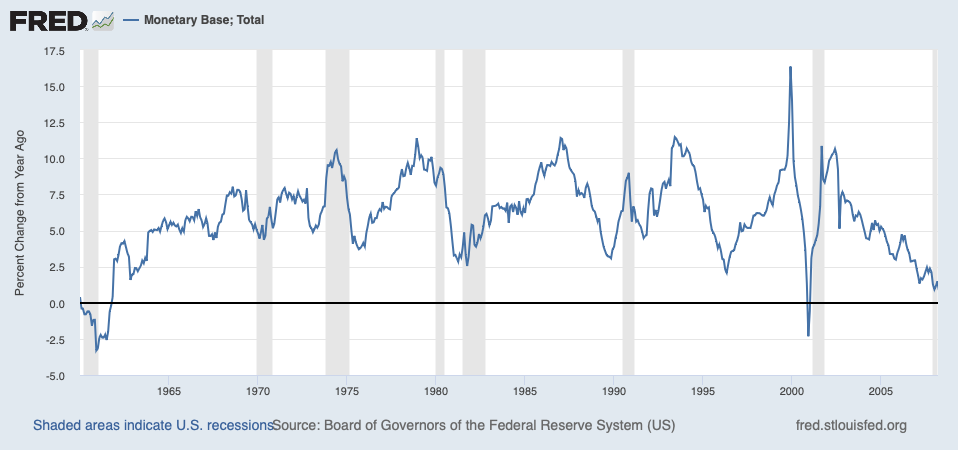

If we look before 2008, back to the late 1950s, what do we see?

During the disastrously inflationary 1970s, there wasn’t really much base money expansion. It doesn’t look “reckless” does it? People at the time didn’t think so either. Yes, base money supply growth did momentarily hit a peak of 10% in the 1974 inflationary breakdown, and again in 1979. Does that mean 10% is “reckless”? It also hit this level several times afterwards, with no particular ill effects. During the 2000-2008 period, there was a huge decline in dollar value vs. gold and other commodities, but base money expansion was the lowest of this entire time period.

If you look at the scale of dollar decline during the 1970s, it is all out of proportion to the modest levels of base money expansion. The Monetary Base in January 1970 was $76 billion. It was $154 billion in February 1980, when the USD hit a nadir vs. gold of $850/oz. That was a 103% increase in a decade. Not a whole lot. Hardly “reckless.”

There is a simple reason for this. As the dollar fell in value, demand for dollars collapsed. People quickly traded their dollars for goods and services.

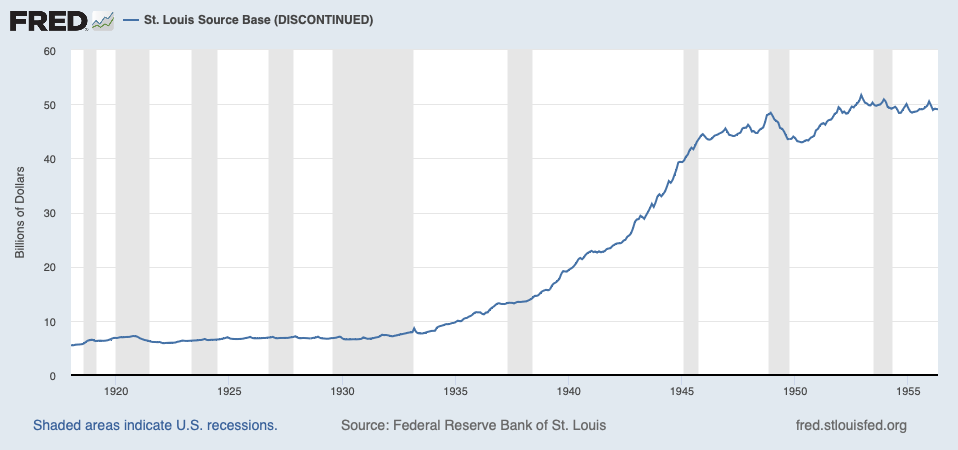

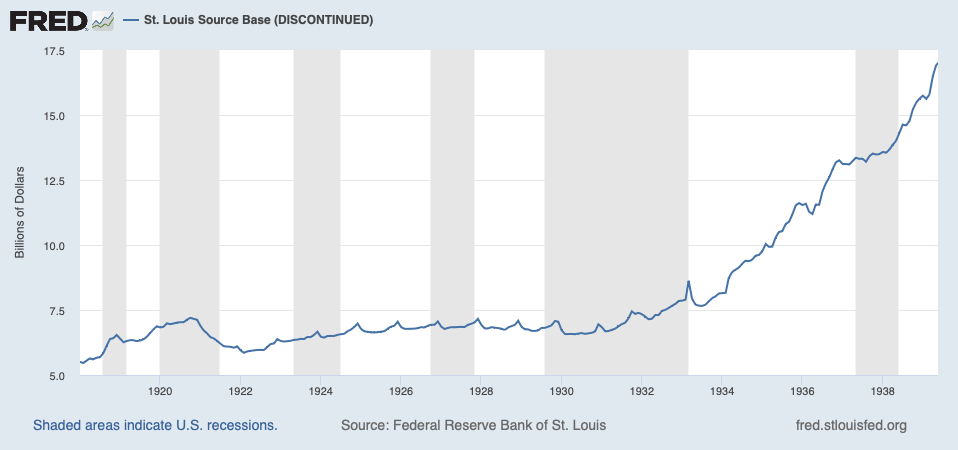

We’ve seen everything from the late 1950s onward. Now let’s look at the period before then.

First, there was almost no monetary base expansion during the 1920s. Also, the USD was securely linked to gold at $20.67/oz. Not much evidence of “inflation” there.

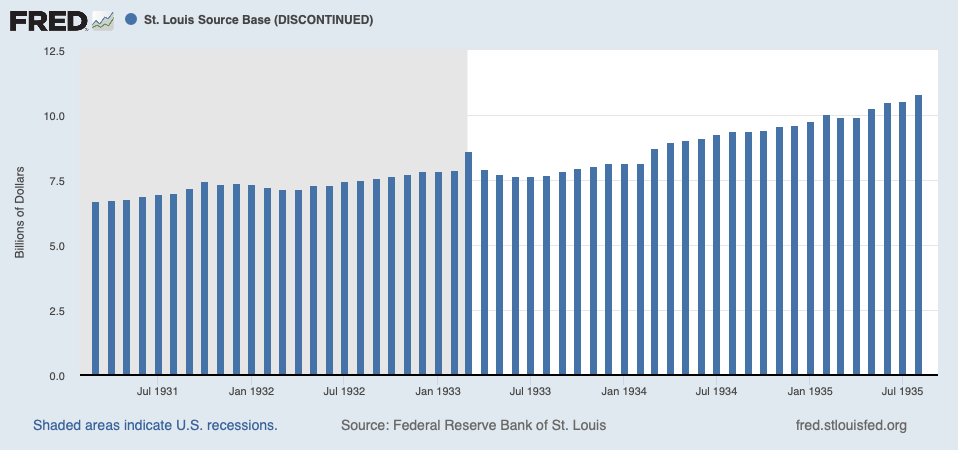

Then, of course, there was the devaluation of 1933, in which the dollar fell from $20.67/oz. to $35/oz. But, this was accompanied by no base money expansion at all!

The dollar devaluation of 1933 was specifically intended to create “inflation,” and of course it worked. But there was still no expansion of the base money supply. Here’s an MGM film from 1933 that explained to the general public what Roosevelt’s strategy was:

After the devaluation, starting in 1934, there was actually a pickup in money creation. This continued through the 1930s and then took off in a big way in the 1940s. There was a huge increase in base money supply between 1933 and 1946, when things again level off. This was about a 5x increase, in 13 years. Five times more money! Was this “reckless”? No, the dollar’s value remained at $35/oz. of gold. There was — similar to the time after 2008 — new demand for bank reserves from banks.

During WWII, there were capital controls and the dollar’s value sagged vs. gold in the London gold market, hitting a low of about $43/oz. However, the dollar’s value was $35/oz. before the war started (1940), and it was again $35/oz. during the 1950s. At least on a point-to-point basis, it did not change value, even despite the 5x increase in the money supply from 1934 to 1950.

So we see that, in the last century of US history, money supply growth and a loss of currency value is not very well correlated at all. This is why we always focus on the value of the currency, not “money supply” alone.

One problem today is that people don’t really have any idea what really happens in economies. They have some vague principles, but not much experience with the real world, where — as you can see — surprising things happen.

These are some of the most rudimentary economic statistics for the United States economy, the most important and most closely-studied economy in the world. We’re not talking about Ecuador in the 1960s here. But, I think that most economic “experts” today don’t really have much idea of what really happened over the last century of US history.

Usually, these principles are pretty good. “Reckless money printing” does cause inflation. Often, this “recklessness” is related to government spending ambitions. But, translating that into the real world, or trying to understand the real world using such crude tools, doesn’t really work, does it?