(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on June 24, 2021.)

Over the years, we’ve learned a number of new things about “inflation.” Since this topic is becoming rather pertinent today, it would be good to go over some of them. Unfortunately, many today still hold odd notions, popular in the 1950s or 1960s, which aren’t really so. Before 1970, people didn’t have that much experience with floating currencies. Since 1970, we’ve had a lot.

The term “inflation” means different things to different people. Ludwig von Mises once tried to establish a precise definition of “inflation,” focusing solely on monetary effects. But, this didn’t go very well. Instead, the term refers to a mishmash of confused concepts. Probably, not much can be done about this. Confused concepts are used by confused people. Since we don’t want to be confused, we should look into the different specific phenomenon referred to by the term “inflation.”

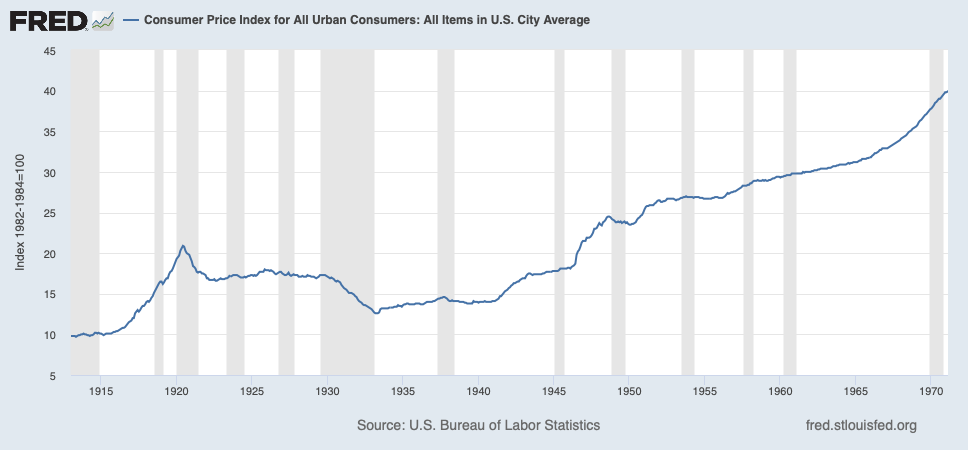

1) A change in the official CPI, or other similar measure of “price changes.” “Inflation” here is simply the +1% or +3% change in some price index. This is a measure, not a process. Prices may change for all number of reasons. Related to this is the idea that the “purchasing power” of a currency also changes, in inverse relation to such a price index; and this change in “purchasing power” is synonymous with a currency’s “value.” This is completely fallacious. When the price of oil, or the whole CPI, doubles, it may be due to a change in the value of the currency, or it may be due to a change in the value of oil, as measured in a currency of stable value. The length of a zucchini might go from “one foot” to “two feet” because the zucchini is actually twice as long as before, and the “foot” is unchanging, or because the length of the “foot” went from twelve inches to six, with no change in the zucchini. These are totally different.

2) Prices may change for a wide variety of nonmonetary reasons. Why did the zucchini grow twice as long, as measured in a “foot” of an unchanging twelve inches? Who knows. In practice, official CPI numbers tend to rise when an economy is growing. As it becomes wealthier, wages and prices for domestic services (restaurants, hotels, education, medical care) tend to rise. Property values and equity values tend to rise. Commodity prices tend to be stable, and prices for manufactured goods tend to decline. Overall, this is typically recorded as a rise in an official CPI number. This is one reason why central banks tend to have a slightly positive CPI target, such as +2.0% per year, which we have seen in the past in healthy growing economies, with no decline in currency value. In very high growth economies, we can see CPI rises of 5%-10% per year, solely from growth effects alone — as was common in Japan during the 1960s, or Hong Kong during the early 1990s. These price rises are entirely benign. Similarly, recession tends to depress prices, as unemployment rises, wages fall, and inventory is liquidated. Prices tend to rise in wartime, and fall in peacetime. Supply/demand issues in individual commodities introduce changes in prices. Thus, we should not assume that a “stable currency value” produces an unchanging CPI, or that changes in the CPI represent monetary effects, or that an unchanging CPI is even desirable.

3) Price changes may come about due to monetary effects. This is when the “foot” goes from twelve inches to six. This arises due to a change in currency value, which would be evident, for example, in the foreign exchange market. For example, if the price of oil is $20, and the Mexican peso’s foreign exchange rate goes from 3/dollar to 6/dollar (perhaps in the space of a year, as happened in 1995), then we should expect the price of oil in pesos to go from 60 pesos to 120 pesos. This happens pretty fast for internationally traded commodities like oil, or imported automobiles. We might then expect the wages of the Mexican worker to eventually double as well, in pesos, to reflect the halving of peso value, “all else being equal.” This process takes a lot longer, probably a number of years and perhaps over a decade, and since all else is never equal, it is not very precise. As these short-term (oil price) and longer-term (wages) adjustment processes take place, it produces an elevated CPI, perhaps rising about 10% per year for a number of years afterwards.

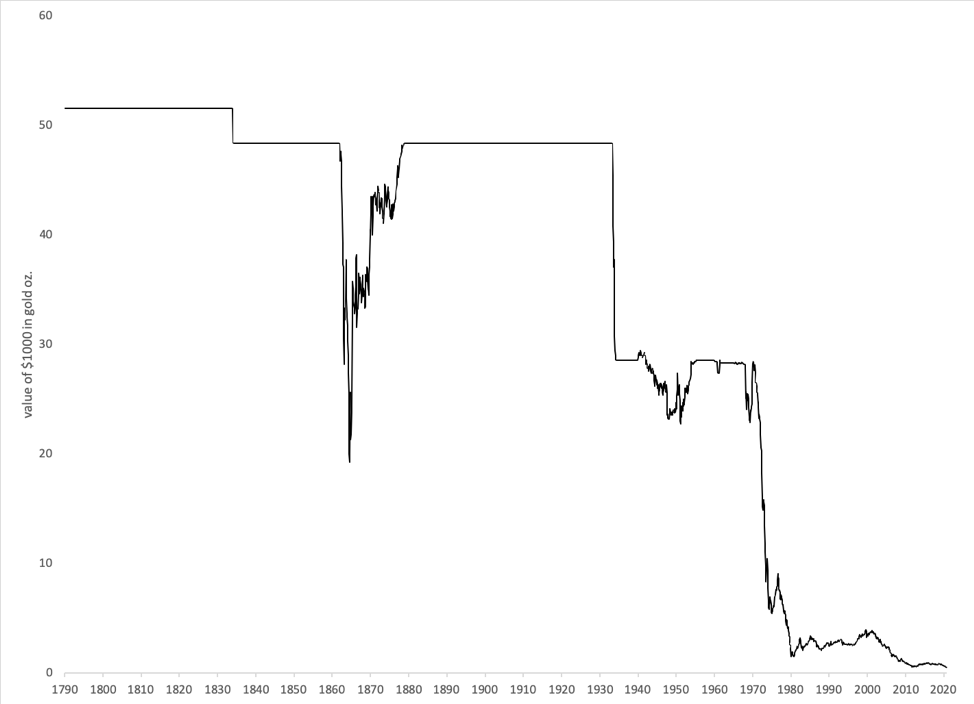

What is true of the Mexican peso is also true of the dollar or euro, but it is normally harder to notice the change. How could you tell if the value of the USD itself fell in half? Gold has always provided a good rough measure. Just as the “price of dollars in pesos” rose from 3 to 6, representing a halving of the peso’s value, so too a “rise in the price of gold” from $1000/oz. to $2000/oz. would represent a similar halving of dollar value, if gold served as a perfect measure of stable value. Even if we choose to ignore gold, nevertheless we must admit that the USD and EUR are floating fiat currencies, and their values could certainly fall in half. This would produce a price adjustment process, as markets for goods and services accommodated the new currency value over time, just as in the example of Mexico. This “price adjustment process” is the consequence of the change in value, which may have happened years earlier.

We will call these monetary effects “monetary inflation.”

“Monetary inflation” is a matter of value, not supply. It has been said that “inflation is too much money chasing too few goods.” But, there are many examples of currencies falling dramatically in value, with little or no change in the actual supply of currency. This happened in 1933, for example, when the U.S. dollar was devalued from $20.67/oz. of gold to $35/oz. of gold. It happened in 1931 in Britain. More recently, it happened in 1998 in Thailand, or 2009 in Russia. It is very common.

Here, the amount of money hasn’t changed. The economy, or nominal GDP, hasn’t changed much either. In terms of “money chasing goods,” nothing significant seems to have happened. But, the value of the currency changed. This produces all the usual “inflationary” effects, even without a change in currency supply. At other times (recently), there can be a very large increase in currency supply, but if this is absorbed by a corresponding increase in the demand for currency, such that the value of the currency doesn’t change, then there will be no inflationary effects. Between 1775 and 1900, the number of dollars in existence (U.S. base money) rose by about 163 times. But, this was absorbed, and in fact necessary, due to the expanding economy during that time. The value of the dollar didn’t change. Certainly, an expansion of supply may lead to a decline in value; but, the “inflationary” effect arises from a change in value, not supply itself. This “change in value” is evident in foreign exchange markets, or the price of gold, among other such indicators.

After 1933, the U.S. dollar’s value was held at $35/oz. of gold. However, the supply of dollars expanded enormously in 1934-1940 (+140%), and much more in 1940-1950 (+124%), ultimately increasing by 440% between 1934 and 1950 — with the dollar still at $35/oz. So, there was “inflation” and devaluation in 1933, without a change in supply; and then a very large change in supply, with no change in value.

From all this, you might naturally conclude that it should be a priority to stabilize the value of currencies. In fact, most of the countries in the world do this — typically, by tying the value of their domestic currencies to the dollar or euro. The U.S. and European countries used to have the same basic idea, by tying the value of their currencies to gold. The value of the U.S. dollar was (in principle) fixed at $20.67/oz. before 1933; and $35/oz. afterwards. A similar policy held for the British pound, German mark, French franc, Italian lira, Japanese yen, and other major or minor currencies.

Most prudent central banks today have a sort of shadowy reflection of this policy. Typically, they want the CPI to not do anything too strange. The Federal Reserve, for example, has a 2% CPI target. But, we have seen that changes in the CPI can come about for all manner of nonmonetary reasons, including healthy economic growth. Also, changes in the CPI from genuinely monetary causes (a change in currency value) can lag years and even decades behind the decline in monetary value (1995 peso devaluation, 1933 dollar devaluation) that caused the rise in nominal prices. This is even before considering that the CPI is a government-produced statistic that doesn’t really exist in the real world; and one whose calculation has been altered many times over the years, apparently to get it to produce a politically-acceptable result. It should be obvious why this doesn’t work very well.

You could argue that gold is not quite a perfect measure of Stable Value. But, it is one that the whole world used for many centuries, even into the prosperous 1960s, with no particular problems. Today, nobody has a better alternative, even in the form of a white paper, and certainly not a real-world system that has stood the test of time.