(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on July 26, 2019.)

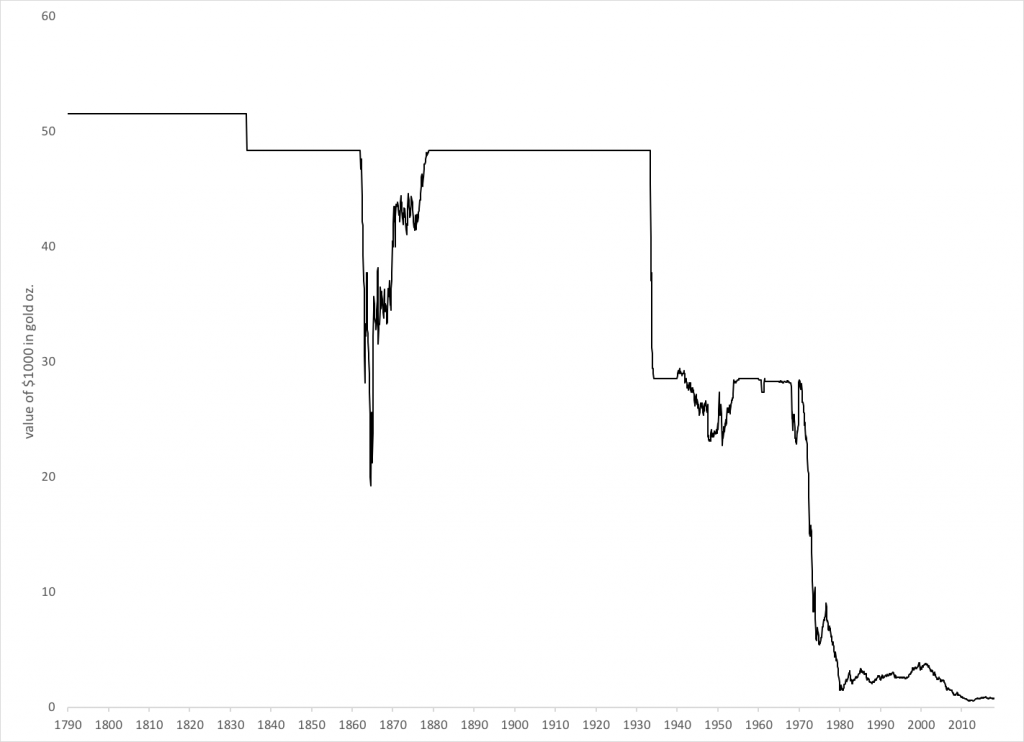

The United States abided by the principle of the gold standard for nearly two centuries, from 1789 to 1971. During this time, it became the most successful country in the world. This was no surprise, for we see the same pattern over and over again throughout the past 2,500 years. The countries with the most stable and reliable currencies do best; when currencies become unreliable and unstable, problems ensue. The Founders knew this; that’s why they set things up that way. It wasn’t just a lucky guess. That’s why Stable Money is one half of what I call “the Magic Formula.”

These basic principles underwent an erosion during the twentieth century. Manipulation of the economy via currency distortion began to fascinate people, as it has throughout the ages. Alongside this, the basic principles behind the gold standard were lost. People forgot why they based their money on gold; and also, they forgot how. This was true across the intellectual spectrum. The Keynesians, Monetarists and others fascinated by monetary manipulation saw the gold standard as simply an obstruction to their plans to manufacture everlasting prosperity through judicious management of the printing press. But also, the remaining gold standard advocates themselves mostly forgot both the Why and the How, and sank into their own forms of confusion and ineptitude, repeating slogans about “fractional reserve banking,” the “balance of payments” and an imaginary “pure gold standard” that had little relation to the real world.

When the Bretton Woods gold standard system ended in 1971, it was after two decades of peace and prosperity worldwide — the best two decades, arguably, of the century since 1914. Nobody wanted the good times to end; and in December 1971, President Richard Nixon himself organized the Smithsonian Agreement among major world powers to keep it going. But, they didn’t know how. The disintegration of the world gold standard system was completely unwanted and unplanned, and was followed by a decade of economic decline. We live among the rubble of that disaster today.

This brings us to the present day, where supposed “experts” can say howling nonsense about the monetary principles that the U.S. (and the rest of the world) followed for nearly two centuries; and get away with it, because their audience knows even less. One such “expert” is John Cochrane of the Hoover Institute, who is no worse than many like him today, and also no better. Cochrane recently wrote:

The gold standard was really a fiscal commitment, not a monetary one. If people demanded more gold from the government than it had in reserve, the government had to raise taxes or cut spending to buy more gold. More often, the government would borrow to get gold, but governments must credibly promise to raise taxes or cut spending to borrow. This fiscal commitment ultimately gave money its value, not the sometimes-empty promise to exchange money for gold. Taxes ultimately back all government money. The gold standard made this fiscal commitment visible and testable.

What does this even mean? For most of U.S. history, the government was not very involved in money creation, except for a few wartime expedients like President Abraham Lincoln’s “greenback” notes. The Federal Reserve was founded in 1913 as a private entity, somewhat in the model of the Bank of England, which was also a private entity. As late as 1930, over 7,000 U.S. banks issued their own banknotes, all of them linked to gold, the tail end of a tradition of a private multi-issuer currency system that dates back to 1789.

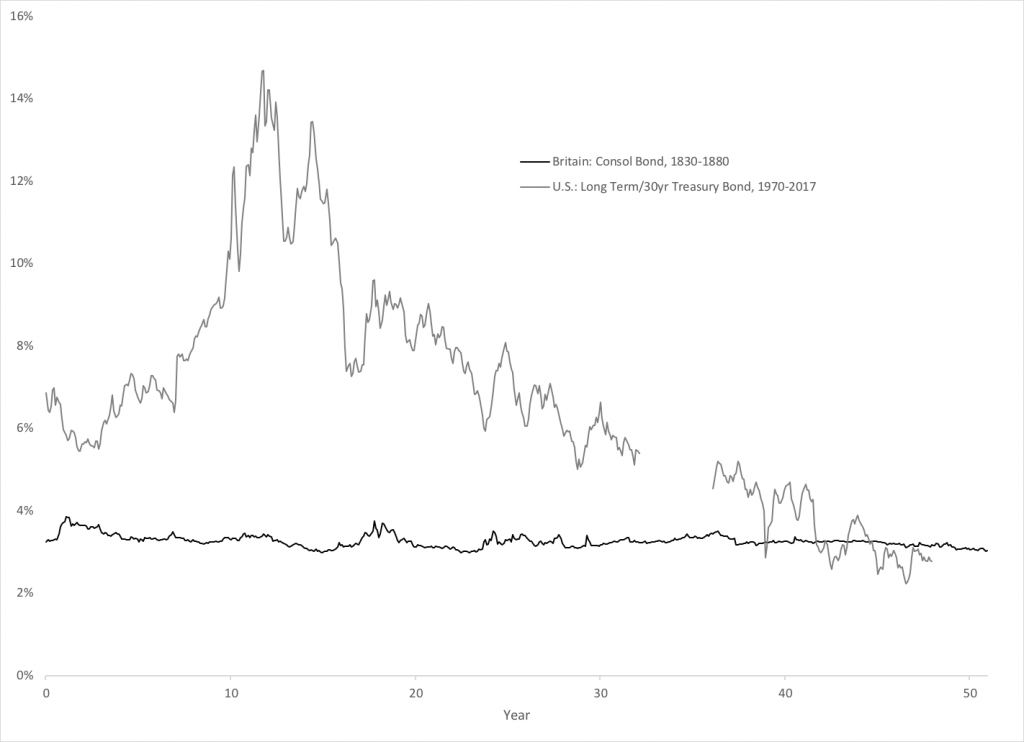

The gold standard is based on the ideal of money that is stable in value, reliable, and unchanging, somewhat like other weights and measures like the kilogram or meter. Linking the value of the currency to gold was found to be the most effective way to attain this. People used to call gold the “Monetary Polaris” — like the North Star, it was the one thing that didn’t move, and thus it could be used as a reference point for navigation. The extraordinary stability of interest rates throughout the gold standard era, and the extraordinary popularity of the gold standard itself, indicate that these goals were achieved.

Cochrane is a fan of CPI targeting, which seems to aim for some of the same goals as a gold standard, namely “price stability.” But stability of currency value, not prices, is the real goal. This might seem abstract, but actually it is very simple. Let’s say that the euro fell 20% against the dollar, from $1.20 to $0.96 for example. (We will assume that this is a fall in the euro’s value, not a rise in the dollar’s.) The value has fallen 20%. We can see it in the foreign exchange market. This 20% move would be a big deal. But that move would not be very well reflected by the domestic eurozone CPI. Presumably, the CPI would rise a bit as a result; but this might easily be clouded by the natural volatility and noise of the CPI. Because it has such a distant and lagging relationship to currency value, the CPI is not an effective means to stabilize a currency. We can easily imagine the value of the currency going up or down 20%, or more, within the context of a “CPI targeting” system. This does avoid extreme changes of value, such as hyperinflation, but it does not achieve stability of value.

Perhaps there is a recession in the eurozone, which would tend to depress prices. Even with a 20% decline in the euro’s value, this recession-related decline in the CPI might prompt an even larger decline in the euro’s value, under a CPI targeting system. Thus, a CPI target that appears to be a policy of maintaining “stable purchasing power” in practice amounts to an excuse to devalue the currency in a recession, which is actually a form of interventionist monetary manipulation. This has always been the case for “stable purchasing power” arguments going back at least to Irving Fischer in 1910.

“Price stability” was never a goal of the gold standard system. Rather, the goal was stable monetary value, which would allow prices to form without being molested by monetary distortion. High-growth economies often have a very high measured CPI, with a gold standard system. During the 1960s, the CPI in Japan rose 70% (5.5% annualized), while the yen was pegged to gold. This was simply the statistical reflection of the extraordinary growth of the Japanese economy in that decade. With fifty years of hindsight, nobody has identified a problem that came of this. But what if Japan did not have a gold standard system, but rather a CPI target that would use monetary means to keep the CPI unchanged? Presumably, this would have required a dramatic rise in the yen’s value; a rise sufficient to exterminate one of the greatest success stories of the twentieth century. The gold standard worked wonderfully, for Japan. A CPI target would have been a disaster.

“A return to gold is unfeasible,” Cochrane asserted, echoing a familiar trope. This is silly. Practical people, even those that know nothing of economics, know that something everyone in the world did for centuries is not “unfeasible.” Over 50% of all countries in the world currently link their currencies to major international currencies like the dollar or euro — preferably, using some kind of currency board-like system. A gold link is not much different than a euro link. It’s just a different “standard of value.”

But there is some truth to Cochrane’s assertion. It would be “unfeasible” for him, because, like many “experts” today, he doesn’t know how to do it. Remember, the Bretton Woods gold standard system blew up in 1971, in the middle of blue-sky prosperity, not because it wasn’t working — the world economy was doing great — but because those entrusted with its maintenance both forgot what it was for, and also how to make it operate. You can’t ask people to do things that they are incapable of; and we should not be surprised that they don’t want to be asked, since they don’t want to make public fools of themselves. I wrote a whole book — Gold: The Monetary Polaris (2013) — to answer the question of How you actually do these things. (The short answer is that you use currency board-like techniques that today maintain currencies’ links to dollars or euros with a 100% success rate.)

The gold standard has a multi-century track record of success. It actually works — better than one might think it could. Proponents of other forms of “stability” — “price stability,” “economic stability,” NGDP targeting, etc. — actually use instability of currency value to achieve these goals. They usually don’t say this, but that is how their proposals work. They are forms of economic interventionism, using monetary manipulation. This has never worked very well in the past, and we should not expect it to work very well in the future either.