Somewhat unexpectedly, I’ve been doing a lot of talking about “commodity basket”-type monetary proposals. The basic gist of these is that a commodity basket is a good proxy for Stable Value. But, the typical (actually only) argument for this is basically the assumption that commodities are a good proxy for Stable Value, by definition. I think that commodities, individually and also as a group or “basket,” have a lot of price (or value) variation basically due to supply/demand issues of commodities. I think that gold is far better proxy, or approximation, of this Stable Value ideal. And, as it turns out, everybody also agrees with me. The whole monetary history of humanity from prehistory to the present has been the abandonment of all other commodity bases for currencies, except for gold.

If you don’t just assume upfront, without argument, that commodities are better than gold, and you actually think about it, you usually conclude that gold is superior, just humans always have for thousands of years. That is why the people that think about it become gold standard fans.

But, let’s set that aside and talk about something else.

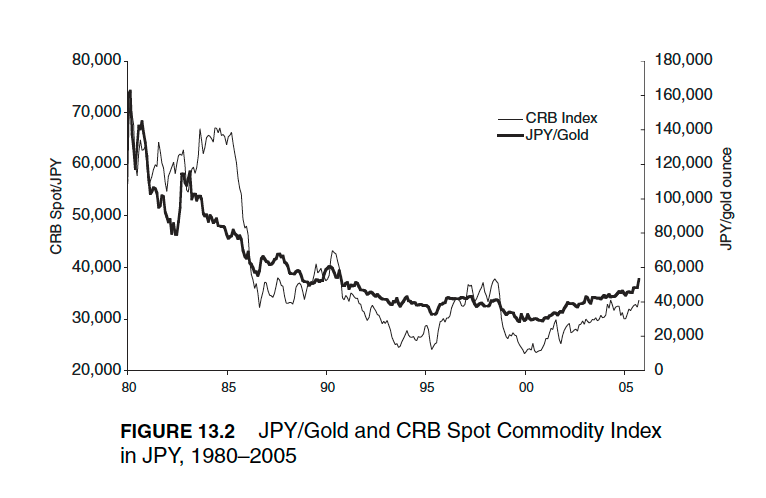

If a currency either rises or falls in value a lot, this will likely be expressed in commodity prices. Commodity prices go up and down a lot for their own non-monetary issues, but if a currency rises a lot (“deflation”) commodity prices are nearly certain to fall, as measured in that currency; and if a currency falls a lot (“inflation”), then commodity prices are nearly certain to rise, as measured in that currency.

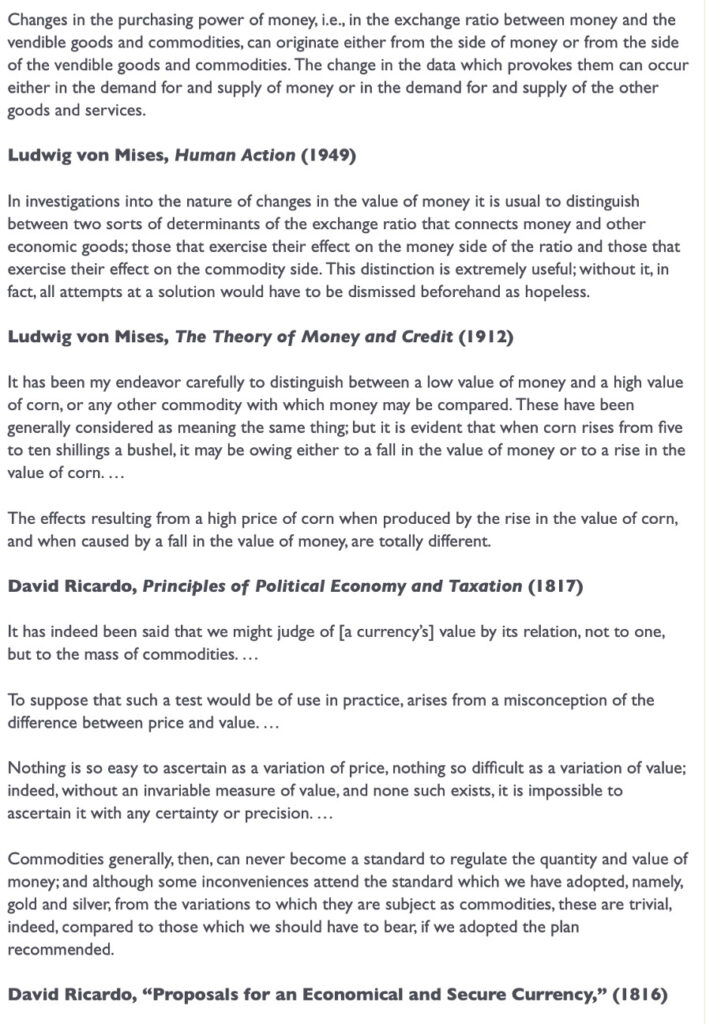

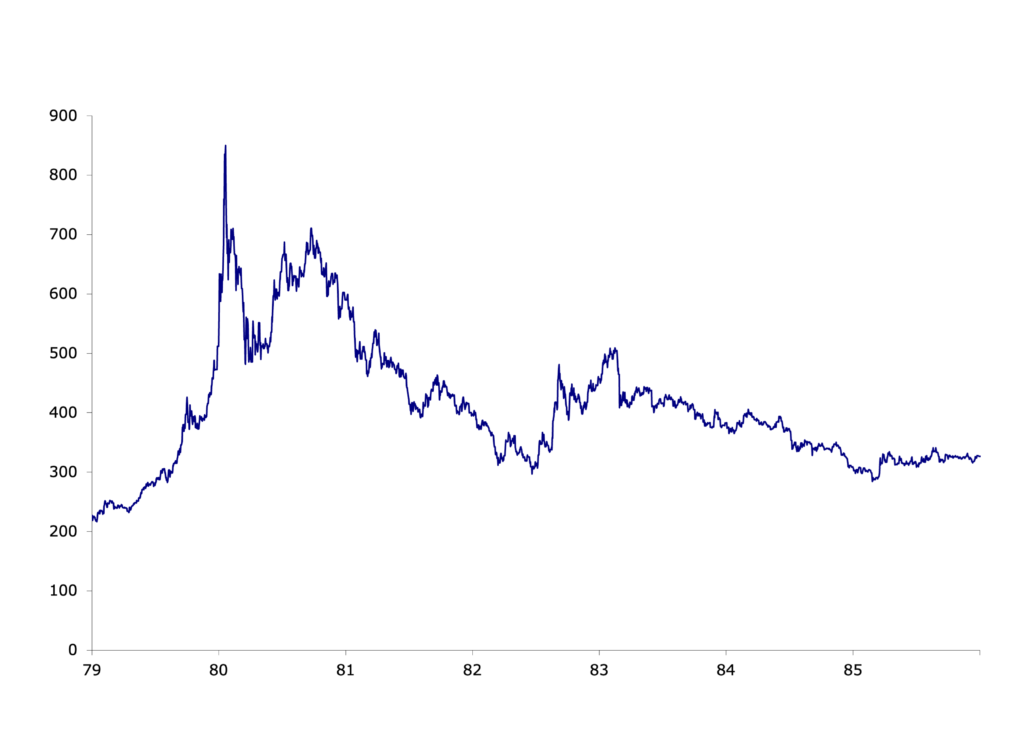

However, the rise in commodity prices (vs. a currency) tends to lag the rise in the price of gold vs. that currency. In other words, the commodities price signal has about a year lag, compared to gold. You can see this here:

It doesn’t always have to be exactly a year lag. In a situation where people have become accustomed to declining currency value, the adjustment process becomes shorter and shorter, until it may be more like a one day lag in a hyperinflationary situation. But, where there is an assumption of stable currency value, where the “Money Illusion” is strong, the lag can be about a year.

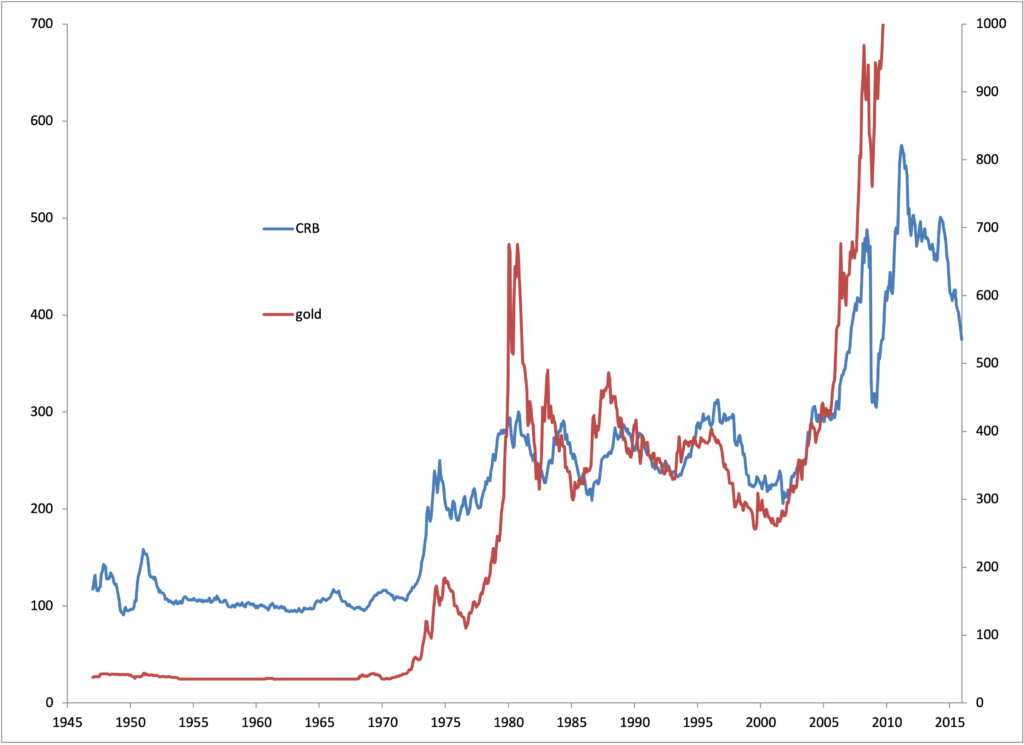

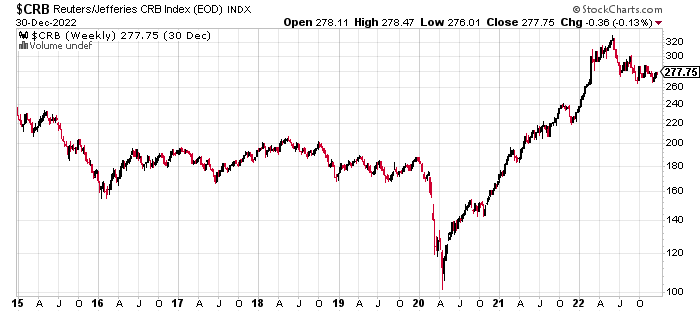

We saw this recently. Gold moved above $1350 definitively in late 2019, eventually continuing to over $2000. This was a clue that commodity prices would follow.

Commodity prices were flattish in 2016-2019, but instead of going up like gold (reflecting dollar weakness related to extreme “easy money” from central banks), they crashed lower, reflecting supply/demand conditions for commodities in the middle of the flash-recession caused by Covid. Was the dollar “strong” (low commodity prices)? No, it was weak (high gold prices) due to the huge expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet taking place at that time.

Gold was telling you that, not only would commodity prices regain their 2016-2019 plateau when supply/demand conditions for commodities normalized, they would go a lot higher, reflecting the lower value of the dollar (takes more dollars to buy an ounce of gold). But, there was a lag. Gold peaked in mid-2020, while commodities peaked in 2022.

This was important, because in September 2020, when commodity prices were barely off the bottom, you could see gold making new highs above $2000/oz. Time to bet big on commodities.

Gold told you the correct story, while commodity prices were not only affected by nonmonetary factors (recession), but also, lagged by many months.

What if the Federal Reserve looked at commodity prices, not gold?

They would have to conclude that, even despite their really over-the-top expansionism in 2020, they were not nearly expansionary enough! They would have to expand a whole lot more. This would of course have been followed, with a lag, by not only the substantial CPI “inflation” and commodity price rises that we saw, but a whole lot more of it! And then what? The Federal Reserve would then have to contract, a whole lot more than they have; and they would also probably have contract way too much, because of the lag in commodity prices, which would have been whiplash both ways. This would have been very unpopular politically, and their commodity-price-targeting system would have been thrown in the junkpile, much like Paul Volcker had to give up Monetarism in 1982 when it was a proven failure.

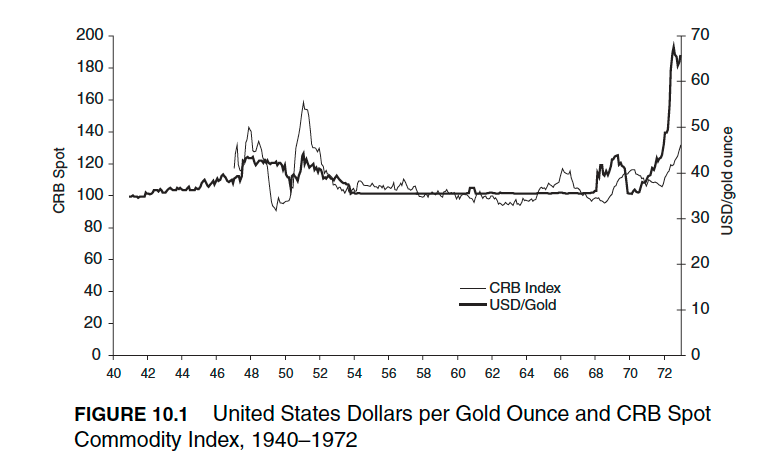

Here’s a closer look at the 1950s to the early 1970s, where the lag is more clearly evident.

Here’s a closer look at the 1950s to the early 1970s, where the lag is more clearly evident.

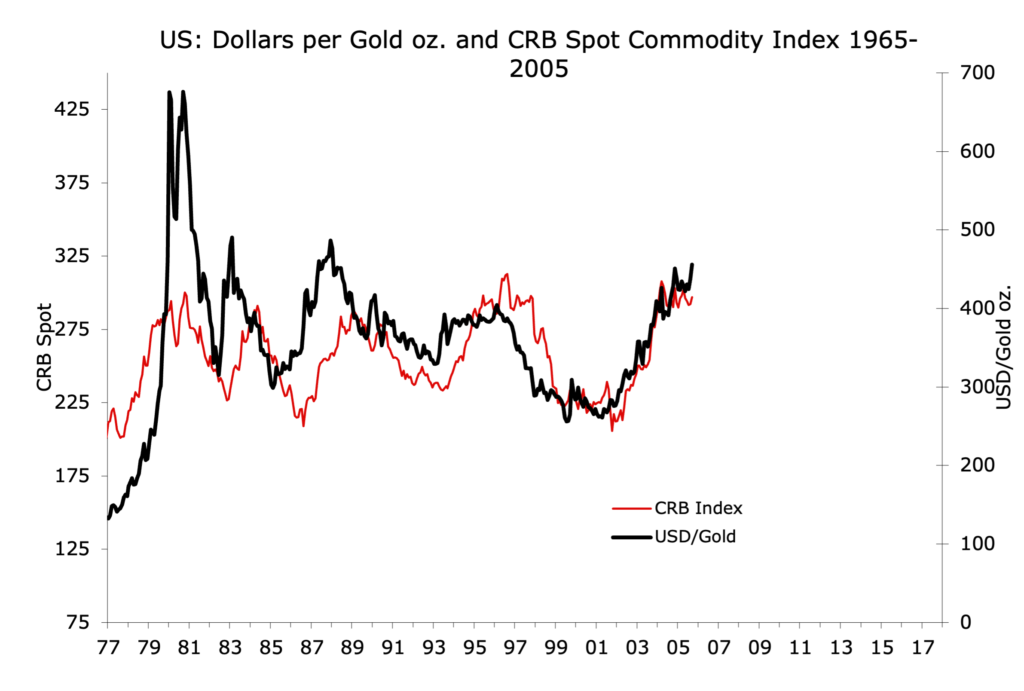

Here’s the lag in the 1980s and 1990s.

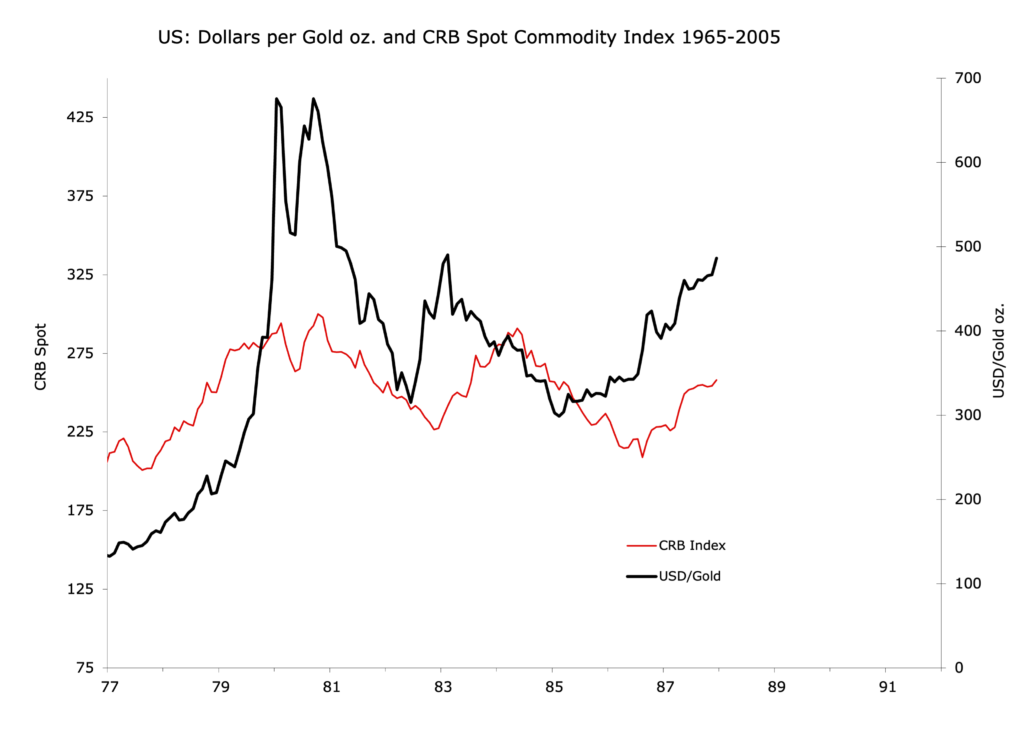

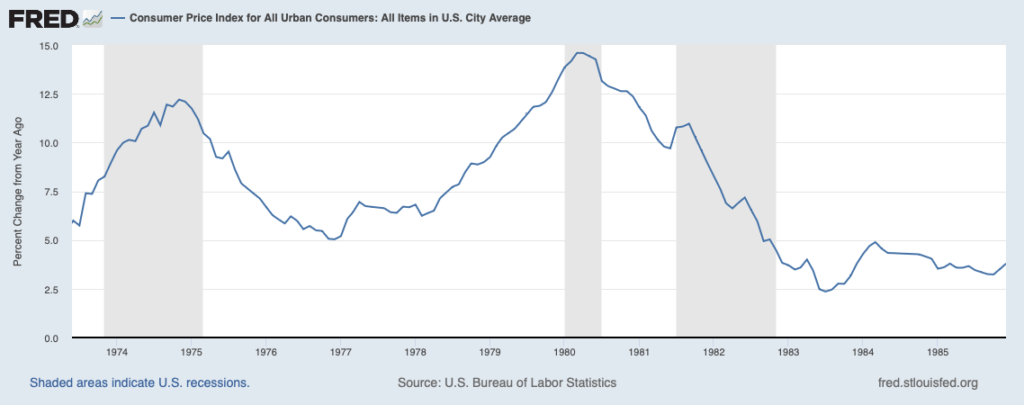

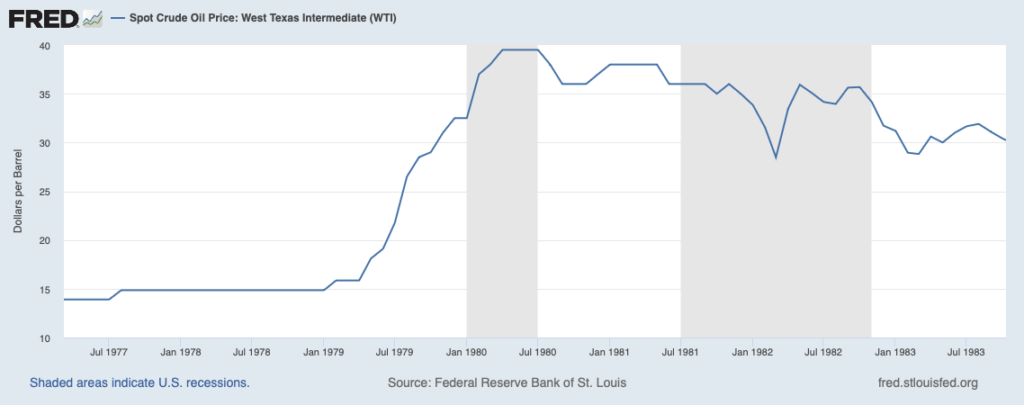

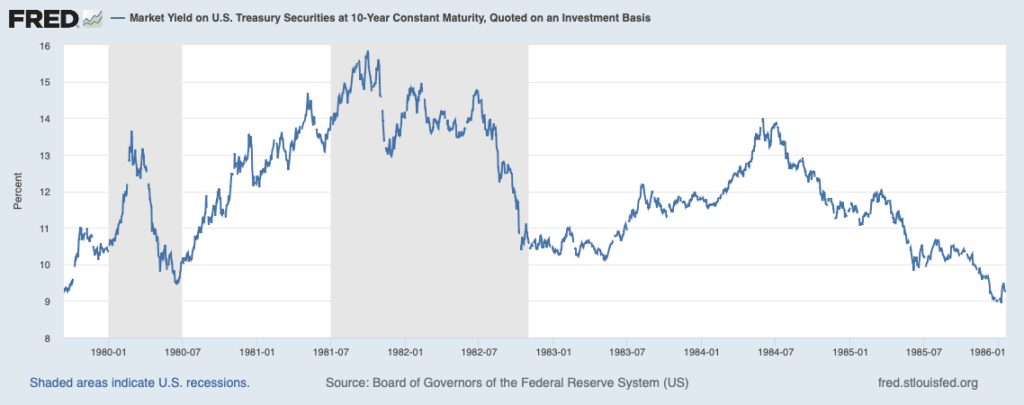

Here’s a closeup of that early 1980s period. Already by mid-1981, gold had a huge decline from its levels of late 1980. The 1yr average ended 1980 around $650, and in mid-1981 USD/gold was around $400. That raised red flags among the gold guys who were yelling about “deflation” and upcoming recession even as the CPI was still over 10%, and commodities had barely budged.

The lag doesn’t look like much on multi-decade charts, but on a month-to-month basis it’s huge.

Crude oil, which is what everyone cared about then, was still near its highs

The yield on the 10yr Treasury bond was still rising.

Throughout our experience since 1971, a commodities basket has failed not only in magnitude, but also in time. Gold has been a much better indicator of currency value than commodities.