In 2021, a substantial new book on the gold standard was released: The Gold Standard: Retrospect and Prospect. This is a collection of papers from a variety of authors, edited by Peter Earle and William Luther, and published by the American Institute of Economic Research, which has long been an advocate of the gold standard going back even to its earliest days in the 1930s. The book actually begins with an essay from AIER commenting on the August 15, 1971 “closing of the gold window” by Richard Nixon, which is pretty good although it has some flaws common to that day.

Back in 2012, I said that we needed a “shelf of books”:

In the little world of gold standard advocacy in the English language, most of the books date from the 1960s and 1970s. Despite their merits, they are also, in my opinion, filled with error. This isn’t going to do the job.

That’s why I took several years myself and wrote a book, Gold: the Once and Future Money. There was no other book out there that I could point to and say: “Here, read this.”

There’s a lot of material in that book – it has about twice as many words as publishers recommend – but there is a lot more still to say, on many topics. That’s why I also have a website, with hundreds of thousands of words of additional text and hundreds of charts and graphs.

But one book – and one author – is not enough. This is politics, and politics requires consensus. We will need a core group of intellectuals, who agree on enough points that a consensus forms that will serve as part of a political “platform.” And, these intellectuals need to write books, so that other people can see what they think.

Too much is done today on the oral tradition. That is, literally, what it is. In this post-Gutenberg age, we have some better alternatives.

Thus, we need what I call the “shelf of books,” from different authors. It doesn’t have to be a big shelf. About twelve good books, recently written, would be enough.

They can’t be old books and they can’t be books filled with economic fallacy.

Since then, we’ve had a number of excellent books, from authors including Judy Shelton, Steve Forbes, Lewis Lehrman and John Butler. We’re not up to twelve yet, but we’re a lot closer than we were.

At that time, I had only one book available. Since then, I’ve added three more. James Turk just released a new book, and I know it’s going to be good.

Since this book consists of separate papers from separate authors, and since it is up my alley, I thought that I would address it in a chapter-by-chapter manner. The first chapter (or paper) is “The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard in the United States,” by George Selgin. Selgin was recently at the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives, at the Cato Institute.

Although Selgin is fairly knowledgeable about the gold standard and its history, he is not, however, a gold standard or “sound money” advocate. He prefers NGDP targeting, which is a floating currency system with an overt purpose of macroeconomic manipulation. It is basically a contemporary version of Friedman Monetarism, or “market monetarism.” This paper actually dates from 2013 — before three of my own books on these topics came out, along with much more detail on my website. So, it is more of a record of the way things were then, than of today. Selgin also had some worthy papers on the gold standard, especially in its pre-1914 versions, in Money Free and Unfree.

And actually, I reviewed this paper, which was also in that book, earlier here:

June 23, 2018: “The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard in the United States” 2: Pretty Good Stuff

To that discussion, I think I will add a little more. Selgin’s paper has some good insights regarding the pre-1914 period, and not too much error, and then tends to be a mess after 1914. This is common. For example, A History of Money, by Glyn Davies, might be the best single history of money available in English, for the pre-1914 period going back to antiquity. But, when it gets to the twentieth century, it is a mess. This is because most of the common views and conventional wisdom for post-1914 period, among academics, is a mess. (This is the problem that I wanted to solve with Gold: The Final Standard). So, if you are to do a review or summary of this commonly accepted history, even if the author cherry-picks his favorite messes from the pile of available messes, you will end up with a mess, as both Selgin and Davies do. If you don’t accept the readily-available off-the-shelf tales, then you will have to develop your own opinion, and obviously it has to be based on something, which takes effort. Then, you will have to listen to the whole economic intelligentsia explain to you that your version of things does not match the various messes they were taught, as if you didn’t know that already. I spent a lot of time, in Gold: The Final Standard and, in greater detail, in many website items such as these regarding the Interwar Period, looking into these various claims and trying to figure out if they had any merit.

October 2, 2016: The Interwar Period, 1914-1944

August 25, 2017: The Interwar Period #2: It’s Not That Complicated

Most people are not capable of doing that. It’s just the way it is. But, we can’t really move forward if people’s understanding of the whole century is a mishmash of error. Such people will not be capable of building functional system in the future. This was one of the lessons of Bretton Woods — the experts were incompetent. Are our experts today more competent? I think the answer is: Yes, they are more competent, but not competent enough, yet. Unfortunately, we will have to rely on “experts.” That is, a group of people, of the kind that you can “institutionalize.” Their knowledge and expertise is not based on individual genius, but can be taught to the kind of reasonably competent people commonly available. It is easily replicable. And, this knowledge and expertise, taught to these bright but common sorts of people, has to be sufficient to actually function in the real world. (That is why we need a shelf of books.) Today, we teach aeronautical engineering to bright people, and they go work at Boeing, and their planes fly reliably. Unfortunately, if you look at the sorry history of monetary failures throughout the last century, and the people responsible for currencies at central banks and governments, it should be obvious to anyone that their planes tend to crash.

July 7, 2011: The Trauma of Bretton Woods

I wrote several books (notably Gold: The Monetary Polaris) that are about how to make planes that don’t crash. Will this generation be the one who can make planes that don’t crash? After a whole century of crashed planes? Obviously, if they can’t figure out why, in the past, other people’s planes crashed — that is, they do not have an accurate understanding of history, or the ability to analyze the situation and come up with a correct answer, which leads to an accurate understanding — then they will not be able to make non-crashing planes in the here and now. This is a topic that I will return to, regarding this book. I think the cryptocurrency stablecoin people, who are mostly computer science people with an engineering mindset, and some financial technicians also with an engineering mindset, probably have a better chance of grasping these concepts than economist types.

June 30, 2019: A Rosetta Stone of Stablethings

Since I already talked about Selgin’s paper in earlier items, let’s move on to the second paper, which is: “How Does a Well-Functioning Gold Standard Function?” by Peter Earle and William Luther. This is certainly my sort of thing, since I wrote a whole book about it, Gold: The Monetary Polaris.

Here is the first paragraph of the paper:

The classical gold standard, which operated from the 1870s to the outbreak of World War I, was a remarkable achievement. As an international standard, it effectively fixed exchange rates between countries and, in doing so, reduced the cost fo cross-border transactions. As trade expanded under the gold standard, producers were able to specialize to a greater extent. The gold standard also encouraged fiscal discipline, since governments found it more difficult to fund initiatives for which the public was unwilling to pay. At the same time, the automatically-adjusting supply mechanism of the gold standard anchored long-run expectations of the price level, which reduced the cost of long-term contracts. Together, these features increased total factor productivity and, hence, the level of real output produced. The unprecedented economic growth realized over the period was, at least in part, a product of the gold standard.

(p. 53)

From this, you would think that the paper is about the Classical Gold Standard, as it actually existed, in 1870-1914. I wrote a chapter about it in Gold: The Final Standard — chapter 5, which you can read for free here. One chapter is not a whole lot, but it does contain actual central bank balance sheet information, weekly for the Bank of England, and yearly for the Bank of France, Germany’s Reichsbank, and Bank of Sweden, so you can get an idea of what real people were doing in the real world. Their planes flew. They were “well-functioning.” How were they made? How did they “function”? Plus, there is info on the United States’ free-banking system under the National Bank Act. Also, I gave some balance sheet info on a variety of other central banks worldwide, illustrating that most of them incorporated reserve-currency systems like a currency board today. Except for the Big Four countries (US, France, Germany and Britain), most everyone else had some variant of a “gold exchange standard,” which is what they called it at the time. I also had some information on gold and silver coinage in circulation, compared to banknotes, and also bank demand deposits, for a variety of countries. I looked into floating currencies of that time period, which were a lot, including the United States, Italy, Spain, Greece and of course the Latin American countries, which were rather badly behaved then just as they are today. I had market interest rates for government bonds from all over the world.

If you really wanted to get an idea of what was going on in those days, the best resource is the 1910 Senate Commission report. It is available here:

February 25, 2017: The 1910 Senate Monetary Commission

It has about thirty volumes, including a whole volume on the Reichsbank (including weekly balance sheet data for 1870-1910), a whole volume on the Swedish Banking System, a whole volume on the National Bank of Belgium, and many other volumes.

Remember, this was 1910. So, it wasn’t history, it was current events. They just asked the people who were really doing it, to explain what they were doing. There are several volumes of just interviews. They would get some central bankers, and commercial bankers, and start asking questions. Some of the answers were pretty interesting.

These were people whose planes didn’t crash. Listen to what they say.

That is where you would start, if you wanted to get an idea of what was really going on in that 1870-1914 period. I think it would be a great topic for a book. Maybe some enterprising academic will try it.

There are vast swathes of economic history and understanding that are free for the taking for anyone willing to give it a shot. For example, I just mentioned that pretty much the whole of the nineteenth century is up for grabs, for any enterprising academic. There are some books that exist about that time period. (I especially like Giulio Gallarotti’s book, although it is the sort of thing only academics could love. Ralph Hawtrey’s books of the 1920s are pretty good, but have too many errors, IMO, to serve as references. Some of Michael Bordo’s work is good.) But, there is so much more to be done. I had to write a chapter about it — a chapter! — because I didn’t know of one good chapter anywhere else. It is like the US just after the Louisiana Purchase. Head West young man! Academics today are like young men in 1810 who grow up on one side of a street in Philadelphia, and wonder if, when they grow up, they can buy a house on the other side of the street. They all want to make a career of mumbling the same old nonsense that some other guy mumbled to them when they were younger. Instead, you can just read the 1910 Report, figure out “hey all that mumbling was wrong!” and make a career of that.

But, that is not what this paper is about. After mentioning it in the first sentence, we wave bon voyage to the real-life nineteenth century and take a trip into fantasyland. The title and first paragraph don’t match up very well with the main point of the paper, but let’s just overlook that for now. The main point of the paper is a sort of mental model, complete with the supply and demand curves a la Alfred Marshall, of gold supply and demand. The basic ideas are two:

- When the “purchasing power” of gold is high (prices are low), then gold exploration and mining becomes more profitable, leading to greater supply of gold from mining, thus bringing down the “purchasing power” of gold. The converse happens when gold’s “purchasing power” declines.

- The amount of gold in the form of coinage will rise when the demand for coinage increases, with this gold coming from existing aboveground non-coinage stocks, such as jewelry and possibly large bullion bars. The converse happens when the demand for coinage declines.

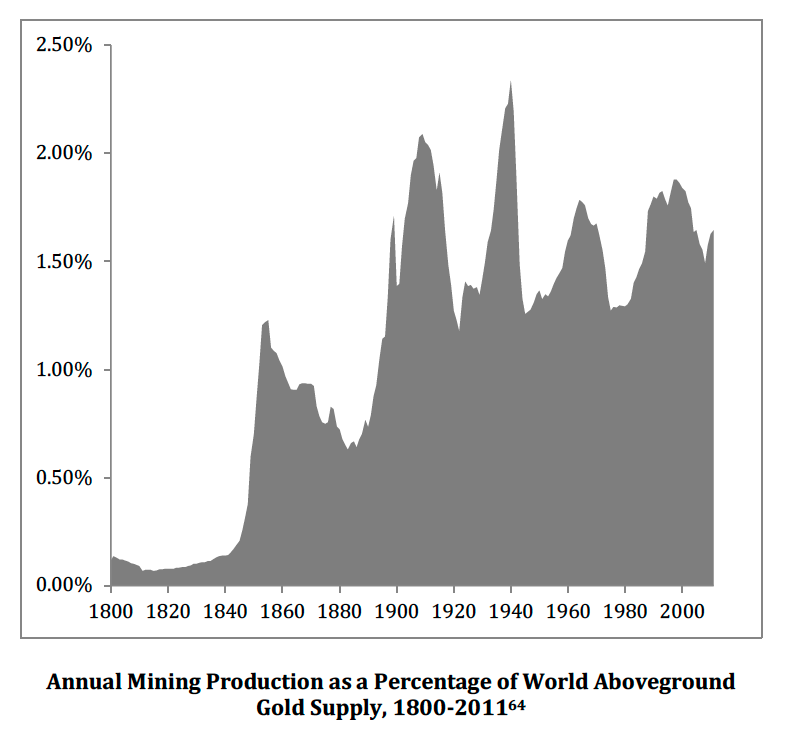

The supposed result of this is that gold’s value achieves some measure of stability. These are interesting propositions. However, I personally don’t like this line of argument very much. This basic idea — that the production of something increases when its price (exchange value) rises, thus dampening price rises, and falls when the price falls, is basic Adam Smith-type stuff. But, what people said in the past was: This does not apply to gold. People in the past — people who actually used gold coins as money, as their fathers and their fathers’ fathers did — said: the value of gold is stable. It does not go up and down in value, as suggested by this model. It is not affected by supply/demand issues, such as variations in mining production, as suggested by this model. Rather, they said, gold’s stability of value seems to have something to do with the very large ratio of aboveground gold to current mining production. For a long time, this ratio was about 50:1. In other words, annual mining production was only about 2% of total aboveground gold.

September 29, 2016: Gold Is “Money” Because It Is Plentiful, Not Because It Is Scarce

So, you can see that if, in a normal year, the amount of aboveground gold went from 100 to 102, then if mining production doubled, it would go from 100 to 104, which is not a very big change. And, if mining production somehow ceased altogether, it would start at 100 and end at 100. Mining is distributed around the world, so it never ceases completely. Also, it is not so easy to double mining production even if you want to. That would take known economic resources of gold, which are not already being mined — not a common thing. Then, you need to raise capital and build a mine, which can take years. In actual fact, gold mining did have some huge increases during the 19th century, which I will talk more about.

Let’s see what I mean.

Here’s John Stuart Mill, from Principles of Political Economy (1848), which was the most popular book on economics during the second half of the nineteenth century.

To the qualities which originally recommended them [gold and silver], another came to be added, the importance of which only unfolded itself by degrees. Of all commodities they are among the least influenced by any of the causes which produce fluctuations of value. … [N]o commodities are so little exposed to causes of variation. They fluctuate less than almost any other things in their cost of production. And from their durability, the total quantity in existence is at all times so great in proportion to the annual supply, that the effect on value even of a change in the cost of production is not sudden: a very long time being required to diminish materially the quantity in existence, and even to increase it very greatly not being a rapid process. Gold and silver, therefore, are more fit than any other commodity to be the subject of engagements for receiving or paying a given quantity at some distant period.

Here’s Michel Chevalier, in 1853:

When mankind, by common consent, and with an unanimity which is deserving of notice, selected these two metals to serve as coin or measures of value, and equivalents for every other exchangeable article, … the circumstance of the value of these two commodities being … little subject to fluctuation, doubtless exercised a decisive weight in the choice. The functions of coin require that the material of which it is made should nearly approach—it can never attain—the condition of fixity of value; for were the material so selected subject to great and sudden fluctuation in value, it is evident, that in employing it as the standard by which all the productions of human industry are to be appraised and exchanged, we should introduce into business transactions an element of uncertainty which would hamper and derange them.

And here’s Ibn Khaldun, in the fourteenth century:

And God created the two precious metals, gold and silver, to serve as the measure of value of all commodities … For other goods are subject to the fluctuations of the market, from which they are immune.

Now, you could say that this is compatible with the model presented here, which is a sort of explanation why gold retains this stable value. But, I think the sense of these passages — all by people who really did use gold coins in their daily lives — was that this supply/demand stuff did not apply to gold.

(Michel Chevalier actually wrote a book where he argued that the California mining expansion would probably lead to issues, and then obviously had to change his mind when it did not. William Stanley Jevons did too, and was just as wrong.)

Rather, this supply/demand equilibrium model applies very well to … copper. Unlike gold, copper does not have large aboveground supplies. Rather, there is only about a two-week supply of bulk copper available. All the copper that is mined is used every year. There is still a lot of aboveground copper, but it is in the form of wiring, tubing and the like.

November 3, 2011: The Supply and Demand for Gold

When the price of copper is low, and copper mining is unprofitable, then expenditures on exploration and new mining production cease. In the extreme, even existing mines might shut down. Supply is constrained. When the price of copper is high, and copper mining is highly profitable, then expenditures on exploration and new production increase. Supply increases, and the price of copper abates. In the extreme, scrap copper supply might expand. Somewhere in between these extremes lies a middling value of copper.

Or, as the executives of copper mining or oil drilling companies often say: “The solution to low [copper] prices is low prices,” and: “The solution to high prices is high prices.”

So, we can see that this supply/demand model might work a lot more for copper. A halving or doubling of world copper production would have huge effects on the market price of copper, while the same thing would have little effect on the market value of gold. Nevertheless, this process does not work very smoothly even for copper, as any review of the copper market over the last century will show.

May 29, 2011: Gold Is Stable In Value #3: Production and Supply

This proposed mechanism seems to work a lot better for copper, than for gold. But, nobody says that copper is, as a consequence, more stable in value than gold. Rather, they say that the value of copper goes up and down, reflecting the vagaries of supply and demand for copper, while gold is stable in value.

The traditional view (which I share) regarding gold is, you could say, a little mystical. Gold is stable in value. It just is — that is our experience, and has been our experience over centuries. How does this come about? It is a mystery. Certainly, the large aboveground supplies compared to mining production have something to do with it. But, this is an argument that mining production doesn’t matter very much — not an argument, as in this paper, that the stability of value is somehow produced by a much more sensitive relationship to mining, as is actually the case for all other metals.

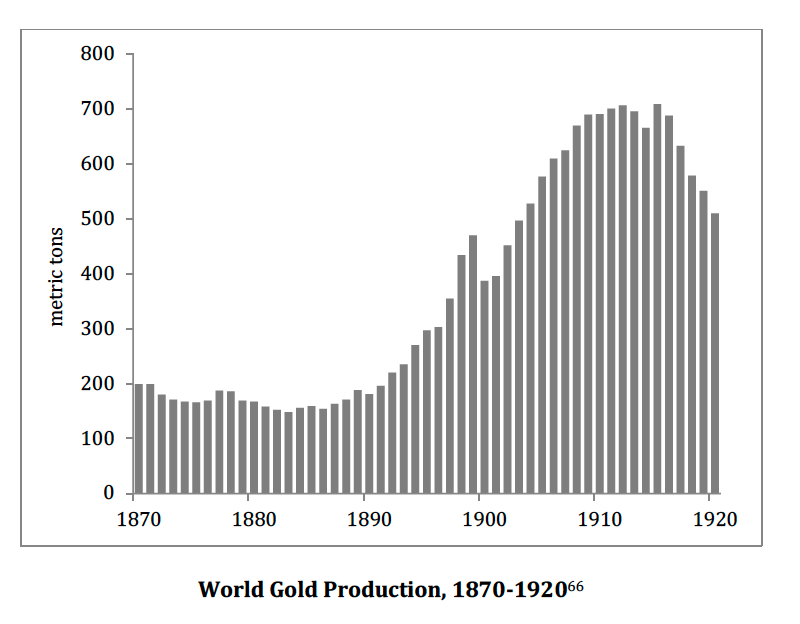

As an example of their principles, the authors use a “shock to the money supply” in the form of the sinking of the RMS Republic and SS Florida off the coast of New England in 1909. $3 million in gold went to the bottom of the sea. This is really just a hypothetical example, to show how their hypothetical model works, but it is nevertheless an example of the kind of thing that the authors consider a “shock.” $3 million, at $20.67 per ounce, is 145,138 ounces, or 4.5 metric tons. In 1909, there was world gold production of 689 metric tons, and estimated aboveground gold of 32,986 tons. Are we to believe that the loss of less than one-seven-thousandth of aboveground gold, to the sea — or 2.4 days of mine production — is “shock” to anyone except the gold’s owners? This is just a hypothetical example, but I think it shows that the authors have an idea of gold’s market value being much more sensitive to very small changes in “supply and demand” than it is. The old writers said: This does not happen.

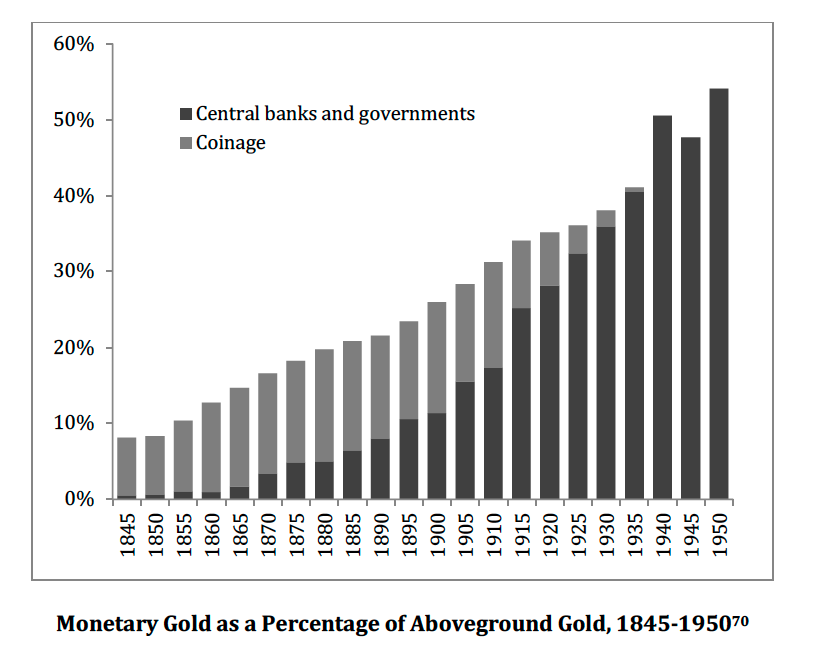

There is a second “equilibrium” function here, which is the movement of aboveground gold from the coinage category to the noncoinage category, and vice versa. This I actually agree with somewhat. We should not be under the impression that, in a 100% coinage system, “money supply” (coinage) is a straight function of mine production. Much of the output of gold and silver mines ends up in noncoinage forms, and bullion does move between coinage and noncoinage states, depending on which people prefer. If you look at historical statistics, they suggest that most of the gold in the world was not in the form of coinage.

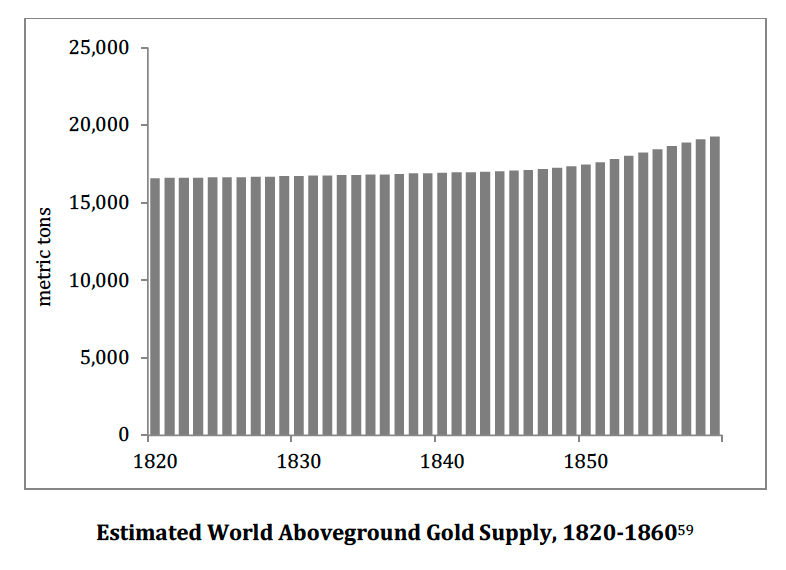

This is from Gold: The Final Standard:

This is, honestly, a little hard to believe. Were gold coins really less than 10% of all aboveground gold in 1845? But, that is the result of pretty good data from Tim Green and GFMS. One conclusion is that it seems like it would be pretty easy to move gold from the noncoinage category to the coinage category, if you wanted to.

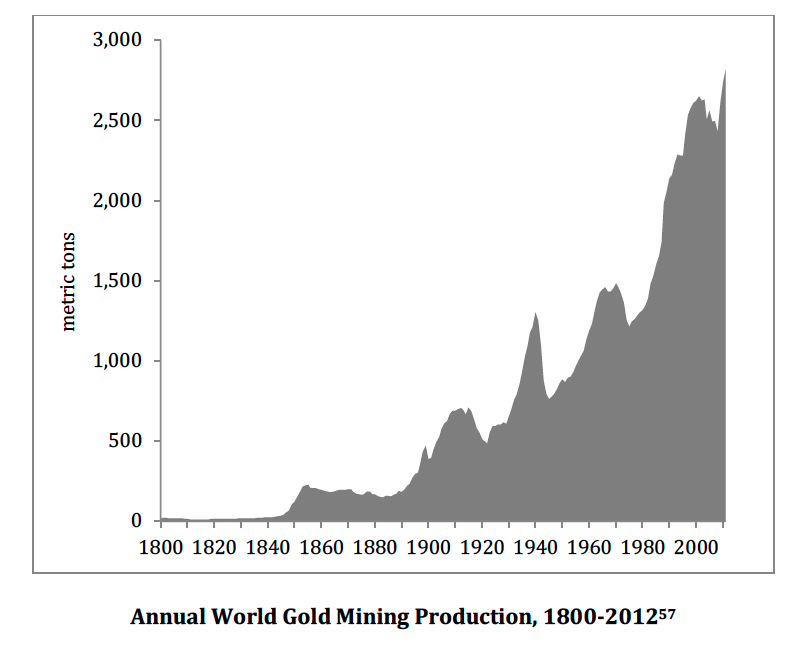

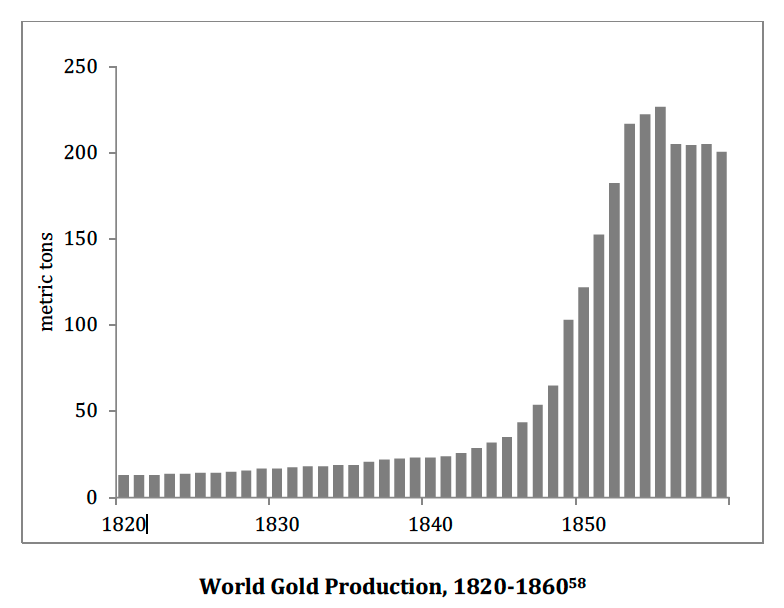

At the end of the paper are a few words looking at whether this hypothetical model seems to operate in the real world. Mostly, it refers to two mining booms in the 19th and early 20th centuries — California in 1848, and South Africa in 1886. I talked about these in some detail in Gold: The Final Standard, with a number of graphs to show what I was talking about. Let’s look.

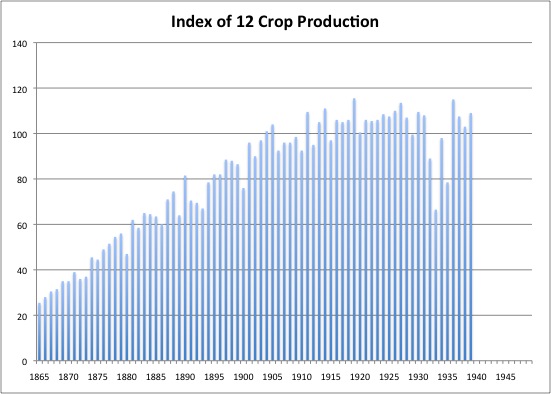

You can see the huge rise of world mining production in the 1830s and 1840s. Actually, there was a tenfold rise between 1830 and 1850, to levels far beyond anything in human history up to that point. Much of this happened before the California discovery. New mines in Russia and elsewhere had already tripled world gold production by 1848. Then, gold poured out of California at an unprecedented pace.

If we are going to make a model where changes in mining production have some kind of effect on gold’s market value, and you were just arguing that losing 2.4 days of mine production to a shipping accident was a “shock,” then this once-in-human-history tenfold increase must have produced some kind of noticeable effect, right?

Right?

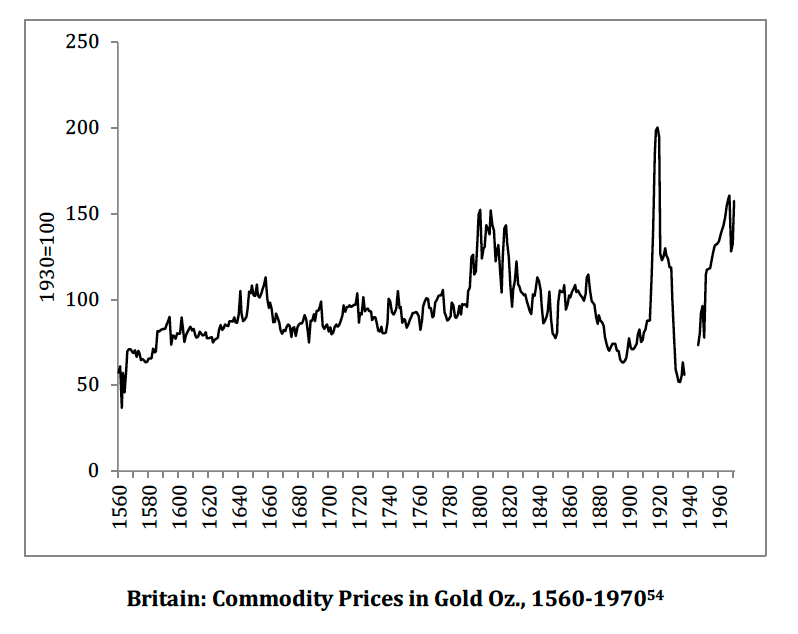

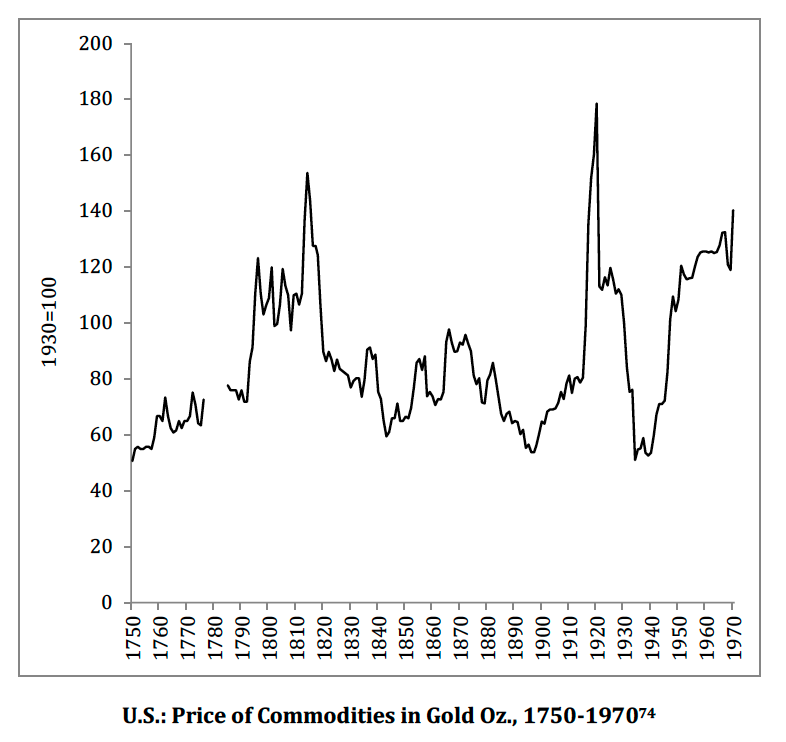

Here are commodity prices in Britain, compared to gold. Britain is a better measure here, since the US was involved in the Civil War beginning in 1861.

Look closely for the gigantic effects of this gigantic increase in gold production.

I’ll wait.

Not much, right?

It’s true that there was a little dip in commodity prices in the 1840s. But, remember that gold production had already tripled, to unprecedented levels, even before California came online. It was probably just something that had to do with commodities, not gold.

Then, as the California mines were blasting out a flood of gold, commodity prices were … just about what they had always been, in Britain, for the previous two hundred years. There doesn’t seem to have been any effect at all.

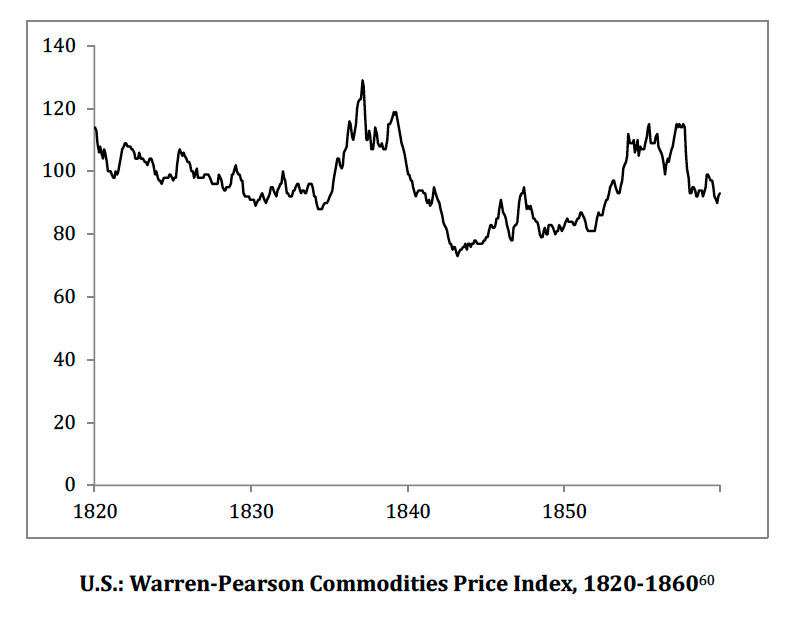

Here are commodity prices in the US, the Warren Pearson Index:

Here we see a dip in commodity prices in the 1840s. This index actually doesn’t even start to rise until about 1852, after gold production had exploded ten times higher. There is a little rise, and then, at the start of the Civil War, after the California mines have been blasting out gold for a decade, on top of the tripling of world gold production prior to 1848, we find that US commodity prices are … almost exactly where they were in 1830.

This makes sense if we remember that, even after a tenfold increase, world gold production was still only a small percentage of aboveground gold. The aboveground gold supply didn’t change very much.

According to the GFMS statistics of aboveground gold (which are disputed by some), even after the California gold rush, world production was only about 1.3% of aboveground gold. Which also raises the question of production before 1830, which was very, very low. Just as the very, very high production after 1850 seems to have had no effect, we must also admit that the very, very low production prior to 1830 seems to have had no effect. Just like the old writers — the ones that actually used gold coins — said: Gold is immune to these supply/demand effects.

The second thing is: The discovery of gold in California was pretty much a complete fluke. It was not a matter of incremental mine expansion in response to incremental increases in gold mining profitability, according to a smooth curve of hypothetical supply of the sort favored by Alfred Marshall. It was a straight up Gift From God, and the profitability of mining was so high that it really didn’t matter what commodity prices were.

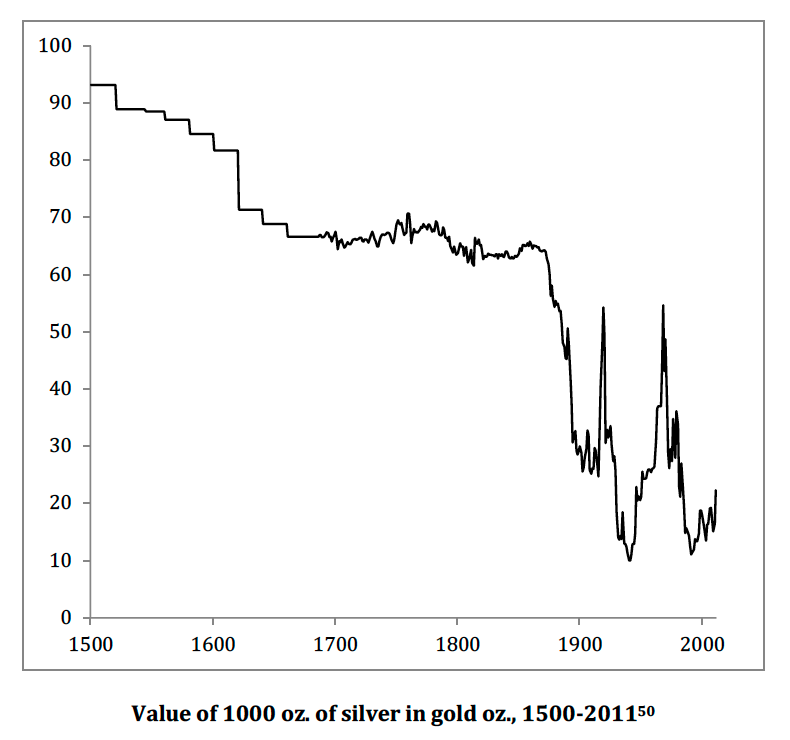

Another clue comes from the gold/silver ratio at the time (which was mentioned by Selgin in the earlier paper).

There was a little lift in the value of silver compared to gold around 1850. This took the ratio from about 16:1 (it took sixteen ounces of silver to buy an ounce of gold) to 15:1 after 1850. Maybe this was due to the flood of new gold coming from California. There was no such change in silver mining. But, 16:1 to 15:1 is a change of only 6%, and was spread over a few years. This is a very small change.

Next, we have the discovery of gold in South Africa in 1886. This led to another huge expansion in world gold production.

Here, the argument that there was some kind of effect on gold’s market value is a little more convincing. Commodity prices were very low at the time. Then, gold production increased, and commodity prices headed back up toward their historical averages after 1900.

The timing here is actually not quite so good. Gold mining began in South Africa in 1886, and when commodity prices bottomed in 1896, gold production had already been soaring for a decade. Gold production in 1896, of 303 metric tons, was already double that of 1886, of 154 metric tons, and at the highest that had ever been achieved up to that point.

Rather, the period was a time of extraordinary expansion of the production of other commodities. As I’ve argued, and which is commonly accepted in standard economic histories of the time (by historians, not economists), the price declines were simply a matter of huge amounts of commodities coming to market.

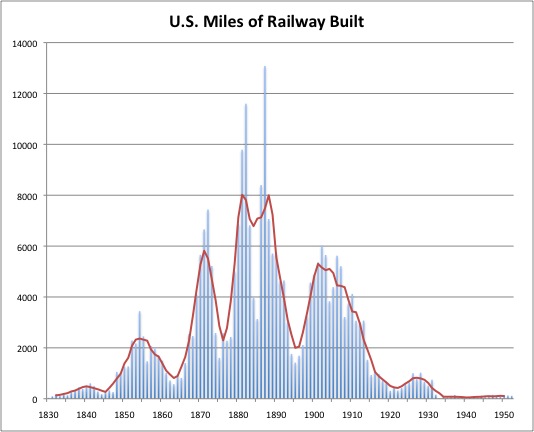

This was a time of the expansion of railways and steam shipping worldwide, which opened up huge tracts of land for agricultural production to be sold on the world market. Before the railroad, a farmer could not move crops much beyond the distance a horse-drawn cart could travel in a few days. With railroads and steamships, wheat from Kansas could be sold in New York, London and India.

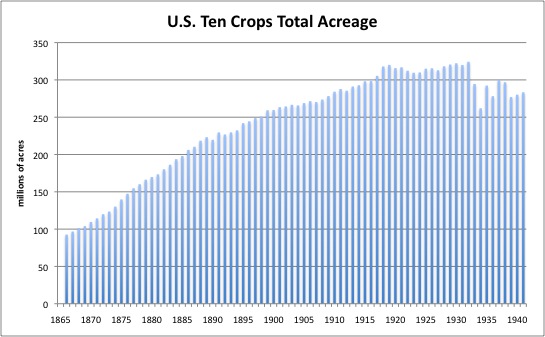

As you can see, there was an incredible expansion of US farming from about 100 million acres in 1870 to about 250 million acres in 1900. Then, it flattens out. In 1940, we have about 280 million acres being planted.

In those days, yield per acre was rather stable, so total production was largely a function of acres under cultivation. There was a giant increase 1870-1900, and then the 1940 figure is barely above 1900. It’s no surprise that, by the 1920s, commodity prices had risen again. We don’t need to make up stories about the supply/demand for gold. The supply/demand for wheat and corn can account for the whole tale.

This was happening not only in the US, but also in Canada, Australia, Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Africa, Russia and Eastern Europe, and everywhere else that British railroad engineers and British capital could combine with local labor.

Usually, economist types like Michael Bordo will try to hedge their bets, and say that maybe it was a combination of both commodity supply and monetary effects. We can’t say for certain that it was definitely all one or the other. But, we have already seen that the gigantic increase in gold production in the 1840s and 1850s had negligible effect. Also, the increase in gold production in the 1890s-1900s still didn’t bring the production/aboveground gold ratio much beyond where it spent the whole 20th century. So, maybe the decline and later rise in commodity prices was almost entirely, or even entirely, a matter of commodity supply and demand, not gold.

(There was a real monetary element at work in the US, but not elsewhere in the world that was using the gold standard in the 1870s. The US dollar was still a floating currency in the 1870s. It’s value was raised during the decade back to its prewar gold parity, a genuine monetary factor influencing USD-denominated commodity prices. The USD returned to its gold parity in 1879.)

There is a general principle in commodity prices, which is: When prices decline while production increases, the decline in price is due to increasing supply, not demand. When prices decline while production declines also, the price decline is due to decreasing demand. Here, we see falling prices and increasing production. During the Great Depression, we see falling prices and decreasing production. If gold was rising in value, that would tend to put a somewhat recessionary effect on the economy. You would expect decreasing prices and decreasing production. One way to look at it is: If gold’s value is “100” (arbitrary), and then rises to “120,” and the price of corn is $1.00 a bushel, then the “real price” of corn rises from 100*$1.00=100 to 120*$1.00=120. When the “real price” of corn rises 20%, people naturally demand less of it. Over time, the price of corn drops to 120*$0.83=100 to adjust to the change in the value of gold. Demand would decline, and production would decline also as marginal producers became unprofitable. Here we see rising production. Nothing having to do with gold makes more corn come out of the ground. This implies that the price changes were caused by increasing production.

In any case, it doesn’t matter much, because the whole period was very good for economies worldwide. If gold did rise in value somewhat, it did not impair economic performance. Most of the problems, especially around 1890-1896, were due to various threats (Selgin outlines them in his paper) that the US would go off gold and devalue the dollar by about 50% via “free coinage of silver.” I bet that would make you a little panicky. When Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected in 1892, people thought that a dollar devaluation (“free coinage”) was just around the corner. But, Cleveland ignored his own party, and also some of the Republicans that also favored a devaluation, and stuck with gold. Soon after, Cleveland allowed the first peacetime income tax in the US, in 1894. Now, imagine you haven’t had an income tax all your life (except for briefly during the Civil War), and then there’s a brand new income tax, apparently inspired by Marxist/Progressive ideas common at that time. (Marx was a strong advocate of the “progressive income tax.”) Do you think that might make you a little nervous? The Supreme Court threw it out in 1895 as Unconstitutional, but that was not certain. Then, in 1896, the incumbent president Cleveland, who betrayed his own Democratic Party by sticking to gold, was himself thrown out. The 1896 Democratic candidate was William Jennings Bryan, whose “free coinage” (dollar devaluation) advocacy remains famous today. Do you think all this might lead to financial and economic disorder? Which would in turn depress commodity prices? It did, which Selgin recounted a little bit. William McKinley’s election in 1896 not only promised that the dollar would stick with gold (like all the major European currencies), but also that the Income Tax and other Marxist/Progressive notions were off the table for the time being. (Until McKinley was assassinated by a Communist.) Hooray! The economy boomed — and commodity prices rose. This coincides exactly with the rise in US commodity prices beginning in 1897, and not very well with the discovery of gold in South Africa in 1886.

Plus, there was a huge international crisis in 1890, the Barings Crisis, which is blamed for an international recession.

The point here is, when you look at commodity prices, you can’t just say “oh that must be because the value of gold rose,” ignoring all these other factors. In other words, you can’t assume that all price changes have a solely monetary cause, “by definition.” You would think this is obvious, but most economists don’t do it. They just say: “Well, gold’s purchasing power is shown by commodity prices, so when commodity prices go down gold’s purchasing power goes up.” This is appallingly stupid — David Ricardo and Ludwig Von Mises complained about the same thing in their time — but that is what they do.

August 3, 2017: The Midas Paradox #3: It’s So Because I Say It Is

When I look at this, I tend to agree with the old writers. Gold’s stability of value is independent of these vagaries of mining production. This has something to do with the very large amount of aboveground gold compared to current production, which is different than most other commodities. Mining production in 1910, of 691 tons, was 41x higher than in 1830, of 16.9 tons. Yet, commodity prices were about the same. Neither relatively high production in 1910, or relatively low production prior to 1830, seems to have had much effect. It is a little amazing.

This is a very different conclusion than the authors, who are arguing that gold’s stability of value comes about because gold is very sensitive to these changes in mining production (like most other commodities).

There were some events where you could argue that an increase in gold production came about because of an increase in the profitability of gold mining. There was a rise in gold mining during the 1930s, for example. Gold mining was relatively unaffected by the Great Depression, while currency devaluations and low commodity prices increased effective profit margins. So, sometimes, maybe the kind of supply/demand effects that the authors describe do come into play. But, the big discoveries of California and South Africa look a lot like blind luck. Also, it looks like it didn’t matter anyway. So, even if gold mining might rise or fall somewhat due to profitability (this seems reasonable), it might not matter even if it did.

Next, I want to talk about motivation. These hypotheses, or models, do not seem to arise because of a desire to figure out what is really happening — a Search For Truth, you could say. As I’ve shown, the actual historical evidence is rather contrary, which is what the other writers, who were living at the time and using gold coins, also said. Rather, it seems to address a contemporary need. People want some kind of answer why gold is supposedly stable in value. The old writers just said: It is, and always has been. They looked back and saw literally thousands of years, the entirety of Western Civilization back to the Babylonians and Egyptians, where gold and silver were used as money, and where their daily experience was that it was reliably stable in value. I too think it is a little mystical. It is a little hard to explain this outcome. Like the old writers, I just accept it, without trying to make up funny tales that are wrong. But, this does not satisfy people today. They want some kind of explanation. So, this kind of hypothesis serves as that explanation. It serves a social purpose.

I think it is wrong, and wrong explanations do not interest me. Like other kinds of lies, you can get yourself caught up in their implications. But, let’s just say that it is novel. We don’t want people to get the idea that this sort of thing is conventional wisdom among the little crowd of gold standard advocates today. It is not. The old writers did not agree with this. I don’t agree with it. Others today that I know do not agree with it. It is the authors’ own creative contribution. But, we can put it out there, and you can make up your own mind about it.

The authors themselves, at the end of the paper, admit that the Strong Form of this hypothesis does not match historical experience very well. The authors retreat to a vaguer, much more long-term view, in which these supposed adjustment processes operate with a delay of perhaps decades:

How good can an automatically-adjusting supply of money be if it typically takes twenty-five years to play out? Although a faster adjustment mechanism would certainly be preferable, the relatively slow adjustment mechanism of the gold standard nonetheless produced desirable results.

Now we are getting rather mystical, which is not really much different than my stance. If you step back from the charts I put above by about six feet, what you see is a very long-term upward curve of gold production and supply, which is more-or-less reflective of the expansion of industrial productivity and population as a whole. We now have much more gold production today than in the past, and much more aboveground gold, to go with our much bigger economy. The same productivity increases that affected copper and iron ore mining, also affected gold, keeping everything somewhat proportional, in the longest timeframes. Conclusions that go much beyond that drift into the unknowable.

And with that (which might be longer than the paper itself), let’s move on to the next chapter.