The Problem With Little Teeny Farms

March 28, 2010

If you look at the history of little teeny farms, it isn’t good. This is usually found in countries where inheritance laws/customs decree that a family farm be split equally between children. This tends to cause farm sizes to get smaller and smaller over time. Per-person productivity declines (even as per-acre productivity rises), because people don’t have enough land to work. The result is grinding poverty — not just a “third world” nonindustrialized existence, but the edge of starvation.

This happened in many countries (see Malthus), which is why the American colonies were so exciting to Europeans. They weren’t restricted to some inefficient little three-acre landholding. They could grab all the land they could handle, thus maximizing their per-person productivity, and also maximizing their personal well-being.

That’s why many cultures have had the custom of passing on the family farm whole and intact to only one child, most likely the eldest son. Women are married off to other families. Younger sons typically have to make a go of it somewhere else. In return for this gift of an estate (or family business), the eldest son typically has to care for the parents in old age. Ideally, each farming family should have the most land that they could possibly handle alone, or maybe a little more.

What happens to the younger sons? They could, conceivably, work as agricultural workers on someone else’s land. By definition, this would be someone with more land than they could handle themselves, or they wouldn’t be hiring anyone. In this way, ideally, the people/land ratio would equalize to the level that maximized per-person productivity with the traditional techniques of the day.

The result was a great surplus of people — all those younger sons and their wives — who needed to find a livelihood that wasn’t in farming. They ended up in the cities, of course, which is where everyone who isn’t an agriculturist ends up. There, they would provide some other sort of good or service. In this way, the economy thrived. If 100% of the people are farmers, there isn’t anyone to make all the things that can’t be made on a farm. If, say, 20% of the people are farmers, that means that 80% of the people aren’t farmers, and can produce all the goods and services of a complex and thriving civilization.

We’ve taken this to an extreme today, where about 2% of the people are farmers, and 98% of the people are engaged in something else. Arguably, we would be better off with a different method of food production, because this system produces horrifically bad food. This different method of food production — more local, higher quality — could well be accomplished by a much larger number of family-owned farms.

Let’s say the total population engaged in food production were to rise to 10%. That is five times more than today. However, in terms of the economy as a whole, it is not that much different. The portion of people that are not farmers goes from 98% to 90%, a 10% reduction. Actually, since about 10% of people today are unemployed anyway, we could move to a 10%-farming situation with no reduction in non-farming output.

Some people have suggested that as many as 30% of the U.S. population could be engaged in agriculture. I’m not sure this is such a good idea. This would mean that the not-farming population would decline from 90% to 70%, a 23% reduction. Having five times as many farmers (2% to 10%) could be a good thing, but do we really need fifteen times as many? They wouldn’t create any more food than people today, although it might be better quality.

You could think about it in money terms, if it helps. Let’s say that the farming population increased from 2% to 10%, a multiple of five. However, the amount of food produced would be about the same, because you can only eat so much, and the land can only produce so much. It follows that the cost of food (at least in relation to the other goods and services) must rise by about five times also. If we assume that we want to pay all those new farmers at least as much as farmers today for their labor (arguably too low as it is), then the total amount of dollars spent must also increase by five times. This doesn’t necessarily mean that supermarket prices would rise by five times, because much of the cost of supermarket food is the processing, not the raw materials. But, you can see the basic idea.

Now how do you feel about having the farming population rise not just five times, but ten?

What is fairly clear is that we can’t — and shouldn’t want to — become a “nation of farmers.” That might have been OK in 1860, because the population in 1860 was 31 million people. There was enough land in the U.S. that all of those people could have as much land as they wanted. Today, the population is about ten times that, or 309 million people. If we had the same ratio of farming population (call it 70%) today as then, that would mean 10x as many farmers, and thus each farm would be about 10% the size. This is a recipe for grinding poverty. I mean Bangladesh-type poverty.

Let’s see what the math looks like. There are about 641,680 square miles under cultivation today in the U.S.. This does not include rather large areas of excellent farmland that have fallen out of cultivation, especially east of the Appalachians. However, it includes areas that may not be cultivable (or shouldn’t be cultivated) in the future, such as areas that demand heavy irrigation, and are causing salinization and depleted groundwater. So, let’s call it a wash and say that the land under cultivation in our ideal “nation of farmers” future is the same as today.

There are 640 acres in a square mile, so that’s 411 million acres.

We will assume a farming family has four people, and that 70% of the population has a “family farm.” That works out to 55 million farming families. Each family would have 7.5 acres.

That is not a lot. Indeed, it is rather too small. Remember, the 411 million acres would produce about the same amount of food as it does today. The main difference is that there would be 220 million people farming, instead of about 6 million today, making the same amount of food (or less) from the same amount of land. Remember that in 1860, all the farmland in the United States was farmed by 31m*70% or 22 million people. Can you imagine the economic contraction this would mean? I don’t mean “the simple life.” I mean “I live in a shack made of twigs on the edge of starvation.”

That would still leave about 90 million people to live in cities, which is three times the entire population of the United States in 1860.

Let’s put it this way: what if five million people — from places like Las Vegas perhaps — wanted to move to Vermont and have a “little teeny farm”? The population of Vermont today is about 600,000. And they already own all the farmland. The math just doesn’t work.

Some people today are going even farther, and suggesting that we have some sort of future by converting today’s Suburbia into micro-farms. The Suburban ideal was always the “little teeny farm,” even back in the 1830s. Instead of adopting the Traditional City design, even in small villages as was common in Europe, Small Town America was built on the “farmhouse on a quarter-acre” model that is identical to suburbs today (except that many suburban plots today are smaller than a quarter acre). The fact of the matter is, this sort of hobby gardening is a grossly inefficient way of making food. Just talk to a real farmer about what he thinks about a quarter-acre farm (actually more like an eighth-acre since some of the land is occupied by the house itself and some other bushes, trees and porches).

Look, I have nothing against growing some tomatoes in your backyard, but it is a hobby, or perhaps a survival technique as urban Russians or Cubans discovered. I can tell you one thing it is NOT: it is not sustainable. You aren’t going to have a civilization that lasts for a thousand years that is based on eighth-acre hobby gardens. There is no example of this in all of human history, anywhere in the world. For good reason too.

This is just a continuation of the Suburban Fantasy! The same old idiot fantasy that has been going on for over two hundred years!

I’ll tell you what can work: you could have 10% of the population on family farms, growing food in a healthy, natural way, and 90% of the population living in cities. The 90% of the population living in cities should be living in a proper city, which is to say a beautiful Traditional City, rather than a Suburban Fantasy of little quarter-acre ersatz-micro farms. 10% of today’s population is 31 million people, which is more than the total number of farmers in 1860.

If 10% of today’s population were on family farms, the average farm size would be about 52.5 acres, which is the kind of nice big farm that a family could operate and make a whole lot of food. The kind of nice big farm that people had in 1860, which is why the U.S. drew immigrants from around the world.

Do you see what I mean when I say there is no alternative to the Traditional City?

Can we stop wasting our time with this “little teeny farm” fantasy?

For the most part, the progressive farmer types — the permaculturists and so forth — have done a pretty good job of outlining how that 5%-10% of the population that might conceivably be involved in food production could go about their efforts in the best way possible. Actually, I think that the progressive farmer types still have a lot to do. Few people seem to have completely assimilated the concepts of Masanobu Fukuoka, who is the most sophisticated farmer type that I know of (and he was a full-time farmer, not a part-timer). The real advantages, as I see it, are from abandoning the European grain/meat/dairy pattern altogether. We should have a lot less meat, a lot less dairy, somewhat less grains, and more vegetables. This would tend to solve the farming issue the easy way: just don’t do it. About 70% of U.S. grain production goes to feed livestock for meat. If you have fewer livestock (much fewer, like 70% less), and that livestock is grass-fed (in the case of beef) instead of grain-fed, then your grain farming needs basically go away.

Thus, I think that food production and cooking/cuisine should be considered as a whole. Just substituting grass-fed beef for corn-fed beef, or organic corn from chemical corn, doesn’t really get us where we need to go.

The problem emerges when this progressive farmer pattern, which might be perfectly good for that 5%-10%, is assumed to be a template for the entire civilization. It’s not a matter of population, either. The world population at the birth of Christ, 1AD (acutally 4 BC but close enough), was 200 million people. For the whole world. And the world population in Babylonian times, 1500BC, was about 40 million, or about the same as the population of California today. But even then, there was a pattern of cities and farms. Two separate and distinct formats. Athens. Babylon. Rome. Beijing. Alexandria. Tenochtitlan. And the farmlands that supported them. What we didn’t have was some sort of homogenous even goo of little teeny farms, or some mixed-up blend that is not properly either a farm or a city.

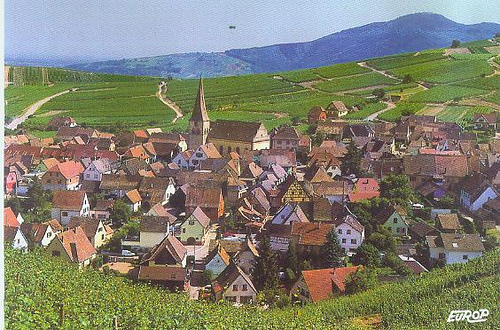

The normal pattern of human development, over the past 5000 years. By “city” I mean an urban place, which follows the traditional pattern of urbanization, which I call the Traditional City. It could be a very small village or a giant metropolis. Here we can see a village which is definitely a village, not a farm, and farmlands which are definitely farmlands, not a village. Two separate and distinct patterns, both serving the needs of the other.

Another example of the same principle, from Germany. A metropolis follows the same pattern, just on a much larger scale.

Sometimes I wonder why these simple and obvious things, which humans around the world have done for thousands of years, have today become esoteric knowledge.

OK, farmer fantasists. I’ll offer this: let’s say 20% of the population was farmers, but that consisted of 5% full-time farmers and 15% part-time farmers, who collectively did the work of another 5% of full-time farmers, so the result is equivalent to 10% of full-time time farmers as described earlier. This is about 62 million people, doing what 21 million people did in 1860.

What about those 15% of the population that are part-time farmers? There are two basic options. One is that they don’t have any other income-producing activity. Thus, they don’t have much in the way of wealth — they live like Buddhist monks — but they have a lot of free time. No 2500sf farmhouse. No fancy horse and buggy. No iPhone. Maybe they have a 450sf strawbale cottage they made themselves, and a bike. But, unlike the family farmer of 1860, they don’t work 12 hours a day six days a week, with a break on the Sabbath. That could work. But it still means 80% of the population is living in Traditional Cities.

The other possibility is that these 15% of part-time farmers also have some other source of income. This would either mean a part-time job, or, for a family, perhaps one full-time worker and another (wife probably) that maybe splits part-time extreme gardening with child-raising and housekeeping.

Let’s look at this arrangement. First, the wife doesn’t have a job — which is actually rare these days. Obviously, you can’t have two parents with full-time jobs plus farming plus kids and housekeeping. Not enough daylight hours.

So, let’s assume that the husband has a job that doesn’t involve farming (because then they would be in the 5% of full-time farmers). Where is this job? Unless they have some sort of Internet business, it probably means the kind of job you’d have in a city, in an office or factory, hospital, retail store or something of that sort.

In short, the person is working in a city, whether a metropolis or perhaps a small town or village.

This family’s primary business is thus the husband’s full time job, not the wife’s part-time extreme gardening hobby. The viability of this arrangement depends on the husband being able to find adequate and satisfying employment, while still being able to live on a piece of land suitable for extreme gardening, which we could put at a minimum of three acres and could be ten or more. This can be quite difficult in rural areas.

So now we have a problem. The house is on three or more acres, but the job is in a “city” of some sort. How does the husband get to work? Today, the typical answer is “in a car.” So, we have automobile dependence built into the equation.

It doesn’t quite have to be that way. You could have a small village that is perhaps a mile or three away, and the husband could commute to the village on foot or bike. Still, you’d have to have some sort of adequate job in the village, which is not that common. (The main purpose of villages in farming areas is to provide services to the local farmers.)

The second option is that the family could live in the village, but the farmland is outside the village. Then, the wife would commute the mile or three from the village to the farmland/extreme garden.

Where are the customers for the part-time farmer? Obviously, if everyone is a part-time farmer, then nobody has any local customers, because everyone is making more food than they eat. The big customers for the part-time farmers would, of course, be people in the cities. So, the food would have to be collected and shipped to metropolitan areas. Although the food may be of very good quality, you still aren’t going to get the “meet the farmer in person at the farmer’s market” experience, unless perhaps the farmer travels to the city to go to the market.

What the farmer fantasists are really fantasizing about, it seems, is the idea of producing food in the backyard of a suburban house in a large city.

There is nothing particularly wrong with this as a hobby, but of course it is hardly even a part-time business at this stage. The typical suburban plot is maybe 1/4 acre on the large size, and it can easily be smaller than that. The house itself and some other niceties occupy some of the area, so the acual area available for food production is perhaps 1/8th of an acre. (In the suburban Los Angeles house I grew up in, the available land would have been more like 1/20th of an acre, and that is only if you used every possible bit.) This might be barely enough to provide fresh vegetables for the family itself, but wouldn’t leave much for the neighbors.

Other comments in this series:

March 14, 2010: The Traditional City: Bringing It All Together

March 7, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to Suburban Hell

February 21, 2010: Toledo, Spain or Toledo, Ohio?

January 31, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York 2: The Bad and the Ugly

January 24, 2010: Let’s Take a Trip to New York City

January 10, 2010: We Could All Be Wizards

December 27, 2009: What a Real Train System Looks Like

December 13, 2009: Life Without Cars: 2009 Edition

November 22, 2009: What Comes After Heroic Materialism?

November 15, 2009: Let’s Kick Around Carfree.com

November 8, 2009: The Future Stinks

October 18, 2009: Let’s Take Another Trip to Venice

October 10, 2009: Place and Non-Place

September 28, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to Barcelona

September 20, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity 2: It’s All In Your Head

September 13, 2009: The Problem of Scarcity

July 26, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 3: How the Suburbs Came to Be

July 19, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village 2: Downtown

July 12, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to an American Village

May 3, 2009: A Bazillion Windmills

April 19, 2009: Let’s Kick Around the “Sustainability” Types

March 3, 2009: Let’s Visit Some More Villages

February 15, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the French Village

February 1, 2009: Let’s Take a Trip to the English Village

January 25, 2009: How to Buy Gold on the Comex (scroll down)

January 4, 2009: Currency Management for Little Countries (scroll down)

December 28, 2008: Currencies are Causes, not Effects (scroll down)

December 21, 2008: Life Without Cars

August 10, 2008: Visions of Future Cities

July 20, 2008: The Traditional City vs. the “Radiant City”

December 2, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Tokyo

October 7, 2007: Let’s Take a Trip to Venice

June 17, 2007: Recipe for Florence

July 9, 2007: No Growth Economics

March 26, 2006: The Eco-Metropolis