(This item originally appeared at Forbes.com on February 21, 2019.)

“Modern Monetary Theory” basically posits that a government can pay its bills by printing money. What exactly is so “modern” about this I don’t know. In the third century, the Roman government started paying its bills by making coins with higher and higher denominations. I don’t think they ever made a “trillion denarii coin” but the value of the denarius eventually fell to less than a millionth of its original value. It is a recipe for disaster; but, even so, every government does it today, to some extent.

The irony of it is: that a government can, in part, pay its bills with the printing press, but this works best when the government acts as if it cannot; for once a government goes too far down this road, the government soon finds that confidence in the currency or the government’s bonds has fallen so far that it can no longer use printing-press finance without disastrous and immediate consequences. In short: it is best if you act as if you can’t, even when you can.

Historically, beginning with the Bank of England in 1694, central banks were private, for-profit institutions. By the end of the nineteenth century, this model had spread over much of the world. Printing money, as you might imagine, turned out to be very profitable. But, in time people complained about this arrangement. During the twentieth century, central banks spread still further, but they officially took on a more public aspect, in which the interest income on their holdings of government bonds were remitted to governments. The Bank of England was officially nationalized in 1946. The Federal Reserve remains a privately-owned entity, but it officially remits its income to the Treasury. I often wonder if this is really true. Since the Federal Reserve doesn’t seem to want to be audited, I guess we will just have to take their word for it.

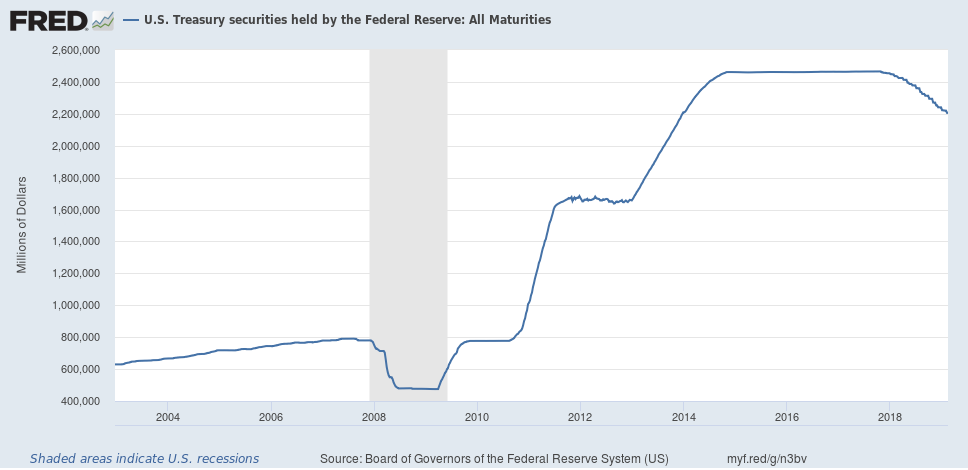

Recently, the Federal Reserve held U.S. Treasury securities amounting to about $2.2 trillion. The interest income from this is remitted back to the Treasury. (In 2017 it was $80 billion, more than any other private company.) The Treasury pays the Fed, and the Fed gives the money back to the Treasury. It is as if the Treasury paid nothing at all. In effect, the interest rate on these bonds is zero. If you issue a bond, and never pay either interest or principal (the bonds are typically rolled into new bonds upon maturity), then it is as if you made them disappear. The Treasury has, over the course of decades, managed to make $2.2 trillion of bonds disappear. This is functionally similar to if the Treasury simply ordered up $2.2 trillion in the form of $100 bills on forklift pallets, and used them pay bills.

So we see that “printing press finance” has been going on for a long time, and at a relatively large scale. The reason that this works is because the Treasury doesn’t get to decide how many bonds the Federal Reserve buys, or, in crude terms, how much “money is printed.” Since the answer might be “zero”–and in recent months it has actually been negative: the Federal Reserve has been reducing its government bond holdings, in effect “unprinting” the money–the Treasury has to act as if it did not have this advantage. The Treasury never gets to say: “we want to fund this program so print us some money,” even though effectively the money is often printed and the program funded.

The Federal Reserve decides. So, how does it decide? Mostly it is a big muddle, but the basic principle is this: the Federal Reserve is tasked to provide the money that the economy “needs” to function. Actually, it is the money that economic participants “demand.” That money in your wallet has to come from somewhere. If “supply” matches “demand,” then the value of the currency will maintain stability. “Demand” tends to grow with a growing economy, so “supply” will also grow alongside–in other words, money is “printed,” with the government the eventual beneficiary. Other factors can affect demand: since 2008, banks have apparently wished to hold much more of their assets in the form of “bank reserves,” which basically means a cash account at the Federal Reserve. The crisis of 2008 has made them much more wary about keeping enough cash on hand to make payments. This is actually a return to old-fashioned banking principles, after a long time in the 1970-2008 period when banks attempted to maximize profitability by holding as little idle cash as possible.

Because we trust the Federal Reserve not to make too many mistakes (rightly or wrongly), we are thus willing to hold (“demand”) a large amount of dollars. Because we “demand” this, the Federal Reserve can thus “supply” a large amount of dollars, and the dollar does not lose value.

But this trust can be quickly undermined if the authority over how much money is “printed” (“supplied”) transfers from the Federal Reserve to the Treasury; and the rationale for how much money is “printed” is no longer the maintenance of a stable currency, but the Treasury’s deficit-financing needs. The Treasury would, of course, claim that “maintenance of a stable currency” is very worthwhile, and that it intends to do exactly that, just as recent MMT fans say that money-printing is ultimately constrained by “inflation.” But what the MMT fans are talking about is what the Federal Reserve is already doing — without MMT. The only reason for the Treasury (per MMT) to use the printing press expressly for financing is because it needs to or wants to; and because it needs to or wants to, it will ignore inflationary concerns, even if it says that it will not, because that is the only reason to embark on this change in the first place.

The funny thing is, if the Treasury did take over the money-printing role expressly for financing purposes, the value of the dollar would probably fall and “inflation” would erupt, even if the Treasury didn’t print any money at all! (In other words, supply was unchanged.) This is because a currency that is now being managed on those principles is, obviously, an unreliable currency; and because nobody wants to hold and unreliable currency, demand for the currency would fall. This is sometimes called a failure of “confidence” or “faith”; somewhat confusing terms to describe a change in the rational expectations of future behavior. If you have falling demand and unchanging supply, you get a fall in market value, which produces “inflation.”

For example: in 1933 president Franklin Roosevelt said that he would devalue the dollar, possibly printing money to do so. What happened is that the dollar fell in value, without any money actually being printed (money supply was unchanged) because who would want to hold a currency that was going to be devalued?

There have been several instances in which the Treasury really did take over the money-printing role. Each time was inflationary — the Civil War, World War I and World War II. The Treasury put a little pressure on the Federal Reserve in the late 1960s to help fund deficits by stepping up its bond-buying; this helped contribute to the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 and the following decade of “stagflation.”

In practice, something like “MMT” has reached a new level of sophistication these days, exemplified by Japan. This really is modern; but I haven’t seen any “MMT” theorist who can explain it. The Bank of Japan now holds government bonds amounting to more than 100% of GDP. In other words, the government has managed to finance itself “with the printing press” to the amount of about 100% of GDP, with no inflationary consequences. This has been possible due to the very large size of Japans’ banks, and the ability of the regulators to “persuade” these banks to hold a very large portion of their assets in the form of BOJ deposits. This in turn has been accomplished by forcing government bond yields to zero; a level at which a bank would rather hold BOJ deposits than government bonds. Since the “opportunity cost” of cash is zero, demand for cash can be very large. It wouldn’t work in the U.S., at least at the same scale, because banks are a much smaller portion of the economy.

It is hard to imagine how this sort of thing can end well. But, it has been going on for some time now — long enough to tempt the MMT fans to indulge in their money-for-nothing fantasies.

When a government keeps its affairs in order, and acts as if it does not need to rely on money-printing to get by, it actually gets a small advantage from the money-creation process. But when a government declares, via various silly justifications, that it intends to use the printing press to finance itself, it typically finds that it cannot without a currency breakdown. Currency traders know that he who panics first panics best; to even talk about this sort of thing is dangerous.