Currency Management for Little Countries

January 4, 2009

In 1971, John Connally reportedly told his European counterparts that “the dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.” Big countries, with international currencies (at this point basically the U.S. and the eurozone), can enjoy a certain amount of autarky with regard to their currencies, at least for a while. Smaller countries have to deal with things a little differently. Since the other 100+ countries of the world that are not the U.S. or in the eurozone fall into this category (I’ll put Russia, China and — sorry — Japan there for now), this applies in most situations.

Many of the differences between smaller countries and the big countries relates to trade. The smaller a country is, the more it tends to trade with the outside world. For example, Guatemala doesn’t have a local automobile industry. So, all the cars that are in the country must be imported. Consequently, since carmakers aren’t giving away their products for free (most of the time), the Guatemalans have to offer something in trade for their cars, like coffee perhaps, or tourism. Consider a city, like Los Angeles. How much of what is consumed in Los Angeles is actually produced in Los Angeles? Probably more than you think, actually, because a lot of “things” that are “consumed” are things like daycare, medical care, landscaping services, restaurants, education, police, fire and other municipal services, plastic surgeons and divorce attorneys. People in your neighborhood stuff. But you can see that if you have a car or a computer or food or petroleum or some construction machinery, it probably has to be imported into Los Angeles from somewhere else. Los Angeles, on the other hand, is busy exporting things like entertainment products or defense industry products.

This turns up in trade statistics. A large country like the U.S. or Japan typically has imports (and exports) of roughly 10% of GDP per year. So, 90% of the goods and services are produced locally, and 10% are imported/exported. However, a smaller country, and especially a smaller country that has embraced international trade (and consequently specialization) can have a much higher ratio, such as 30% or even 100%+. (You can go over 100% if you import goods, do additional manufacturing/value added, and export the resulting products.) Since Los Angeles has about 17 million people, imagine the trade situation for a country like Slovakia, with a population of 5.4 million.

Along with free trade typically comes encouragement to promote open flows of capital as well. This can be where things get tricky. There is nothing inherently wrong with open capital flows. If a building in Los Angeles is financed by someone in New Jersey — so what? However, for a Slovakia, it’s rather more problematic because there are different currencies. Is the loan denominated in Slovak Koruna or in euros? Probably, a potential foreign lender would rather be denominated in euros. And, it is quite likely that the differential in domestic and foreign interest rates, and general capital availability, is such that the borrower figures this might not be such a bad thing. Heck, the borrower might be a foreigner! If it is a German buying a vacation house, or a multinational supermarket chain financing some new stores, or a portfolio investor buying some sort of equity or debt, they may be inherently denominated in euros anyway.

With all of the cross-border trade and financing going on, the Slovak government concludes, quite reasonably, that it would make sense to stabilize their currency against the euro. Maybe even a peg of some sort could be established. Let’s join the eurozone and use euros! However, in a truly bizarre policy, the eurozone has determined that countries like Slovakia have a hazing period in which they are expected to stabilize their currency against the euro, but sort of loosely, without a peg or currency board, or actually using the euro. This is completely bonkers, but that is normal these days. For other countries, like those in Latin America or Asia, perhaps a dollar peg would be more common.

Typically these “pegs” are either sort of informal, such that the currency floats against its benchmark (dollar or euro) but doesn’t stray very far, or they are the sort of ad-hoc currency peg in which the exchange rate is fixed, but through a variety of manipulations and government bullying, rather than the proper technique of using a currency board. This second type was very common in the 1990s but is rarer today, due to the fact that they blew up spectacularly in 1997-1998.

But, the businessmen observe that the government has some sort of euro-peg currency policy. And, after a few successful years, it appears that it works OK. So, they are happy to finance in euros and dollars. In any case, those that do finance in euros and dollars tend to enjoy much greater access to capital and much better interest rates, and will tend to undercut and eventually buy out their competitors that do not. So, there is a competitive issue here.

However, at some point, there is a panic of some sort. Often it is set off by a rise in the benchmark currency, such as the euro or the dollar. There is great pressure to trade, for example to sell Slovak assets or to pay off loans denominated in dollars or euros. This creates a lot of activity on the Koruna/euro exchange.

At this point, the various ad-hoc “we’re just winging it” currency management policies are unable to accomodate the dramatic flows. This sets off even more dramatic flows, because everyone wants to get out before the government’s management of the exchange rate blows up.

Now, none of this would happen if the currency-peg policy were properly managed, via a currency board, or at the very least through the use of currency-board-like techniques involving the direct reduction of base money (unsterilized intervention). We talked about this in the case of Russia:

November 16, 2008: How to Stabilize the Ruble

November 23, 2008: Redeemability and Reserves

November 24, 2008: Russia’s Currency Crisis

Thus, the small country government should be aware that:

1) Trade and external financing tends to be much more significant for smaller countries.

2) This has foreign exchange implications.

3) It is very natural to use some sort of currency-peg policy. If the government goes this way, it should implement either a fully-functional currency board or even just use the foreign currency (euroize or dollarize).

4) If the country wants to have an independent currency, it should be aware of the currency-board-type methods of direct supply adjustment (unsterilized intervention) that will allow it to deal with heavy currency flows.

and finally:

5) A gold standard provides many benefits, but the greater the amount of trade and foreign financing involvement there is, the more this may tend to conflict with the advantages gained by keeping exchange rates stable with another major currency. There is no easy resolution here, unless the major currency (or possibly a collection of smaller currencies) also agrees to peg to gold, in which case their exchange rates become stable, and all the conflicts are resolved.

All of these are variations on the theme that governments and currency managers of smaller countries have to deal with different conditions than do the Fed or ECB, and should understand the proper techniques to address these conditions.

* * *

Predictions for 2009: Martin Armstrong is, or was, the writer of an investment newsletter. You know, one of the hundreds for which you probably get blurbs in the mailbox every day. However, Armstrong is perhaps the only one thrown in jail for seven years — without charges! There was eventually a charge: “conspiracy to commit fraud,” for which he received an additional five years of imprisonment. The evidence: his market calls were a little too good.

http://www.gold-eagle.com/editorials_08/bloom122908.html

People don’t just get thrown in jail, without charges, and then again for baldly idiotic trumped-up charges, for nothing. Obviously, something is up. Which is why you might want to read Armstrong’s latest (October 2008), seventy-seven page opinion on where the market, economy, and planet is heading. It’s mostly cycle theory, in the spirit of W.D. Gann or Elliot.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/8813084/Martin-Armstrong-October-2008-Its-Just-Time-77p

* * *

An entirely different sort of cycle theorist, based on the “four generations” theory of Strauss & Howe:

http://www.jamesgoulding.com/Downloads/WIC.pdf

* * *

The UAE is definitely making moves toward a new gold currency. However, I think they are hesitant in large part because they aren’t sure how to pull it off. That would make me hesitant too.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/112731-will-the-new-gcc-single-currency-include-gold

* * *

Wall Street Journal: “There just aren’t many creditworthy customers now”

Across the U.S., a host of community bankers like him are making daily

decisions that affect how the U.S. makes it through this recession and

credit crunch. They walk a fine line. Holding to lending standards that are

too strict can worsen the local economic toll. Being too lenient can run

afoul of newly nervous bank directors and regulators, or endanger the

bank’s own survival. Add to that the tension of making hard decisions about

customers who are also neighbors. The experience of these bankers also

shows one reason it’s proving hard to jump-start the economy through

more lending. Some of the small-town bankers say there just aren’t all that

many creditworthy customers who wish to borrow [money] now . . .

This is what I was trying to get at a few months ago:

October 26, 2008: Too Much Borrowing Vs. Not Enough Borrowing

I think that was one of my more incoherent posts. I’ll have to revisit the theme at some point. I suppose I was trying to say that the notion (it is a sort of fantasy) that a recession can be prevented by “more credit”, achieved through some sort of central-government jiggering, is totally contrary to reality. The credit contraction is not irrational, it is rational.

* * *

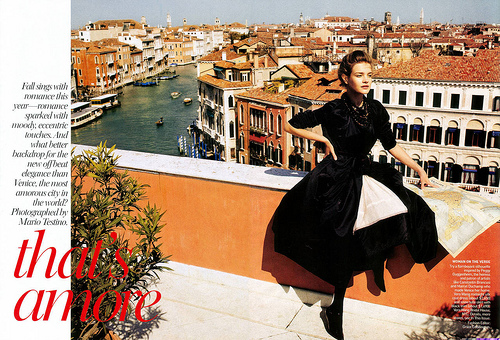

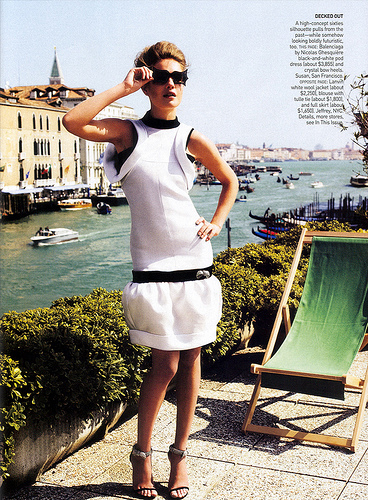

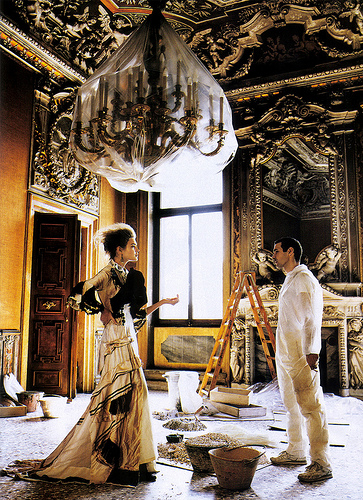

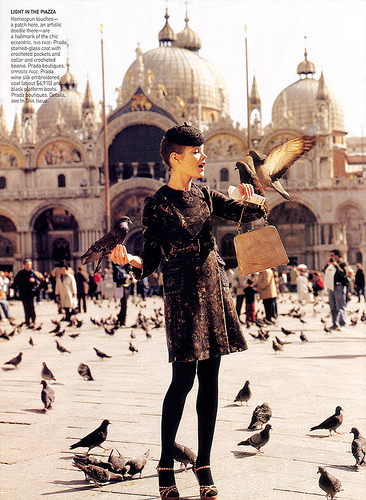

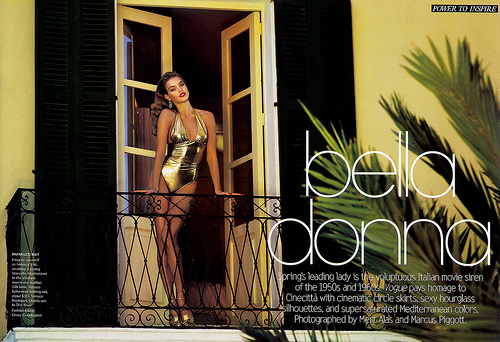

Vogue: We don’t do ‘burbs. Vogue magazine kindly steps in with some nice photos of a no-car environment (Venice). And, helps us fill our hot European women quota. When I go on and on about Really Narrow Streets, it’s because I already know this is what everyone wants, they just don’t know it, or how to do it. That’s why it’s in Vogue. Duh!

What’s with the chicks? Even guys who only care about money … also care about one other thing.

Consider it a how-to lesson on living in a no-car environment.

Not something you’re going to wear to WalMart. But, you see it fits right in here. So, when I say that Really Narrow Streets = hot Russian women, it is not so much of a joke as you might think. (I met Natalia once at a New York fashion show. I think I was the only one there who didn’t know who she was.)

An appealing city environment inspires cultural sophistication on all levels.

Nice building! No cars!

You can’t see the city here … but do you think she’s looking over the strip mall parking lot? Going with the bathing suit, she could be overlooking a beach — another no-car environment.

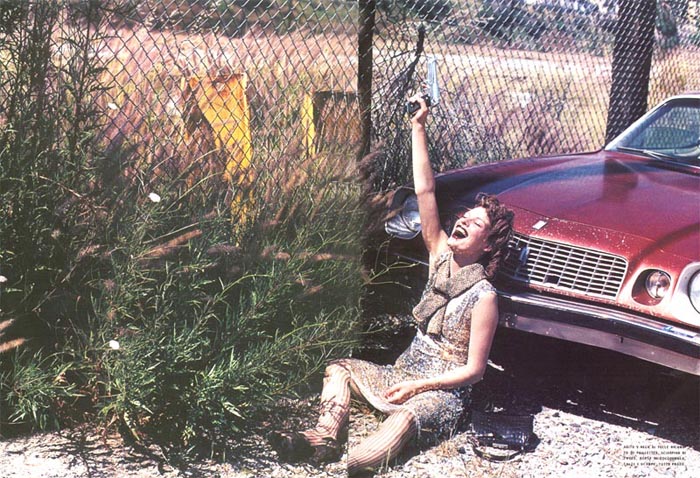

Vogue also does shoots with cars included sometimes. It inspires a different sort of theme …

Vogue Italy, September 2000

Anaheim, California. I grew up near here.

An environment wholly given over to automobiles.

Don’t expect Vogue to show up anytime soon.

And put the gun down!

“When are you guys gonna learn. It’s so easy. Just three words.”