In the past, I began discussing the topic of Economic Nationalism. Then, mostly, I avoided it, because I think I would become unpopular among my friends as tariff supporter. Nevertheless, I think we can make some arguments in favor of Economic Nationalism; so let’s see what those arguments are. With Trump and JD Vance likely to become president and VP, we have the risk now of bad economic nationalism. We should have good economic nationalism. How are they different?

January 10, 2021: Economic Nationalism

March 18, 2018: Economic Nationalism

October 24, 2021: Rationalizing Tariffs

August 1, 2021: Stagnant Wages

May 16, 2021: The Current Account Deficit

February 7, 2021: The Bottom 30%

January 24, 2021: Adam Smith On The Capital/Labor Ratio

I was thinking of writing a book about this. I would spend some time accumulating information and doing research on all the related topics, and reading all the most common existing arguments on both sides, so I could make an informed presentation. But, things are progressing faster than I can write books. So, let’s continue with discussing the topic, in the typical website mode of collecting interesting bits along the way, as a process of discovery and ongoing discussion.

The Free Traders tend to talk about “general economic principles.” Free Trade (no taxes on trade) is obviously better, at least in some ways, because, as a “general economic principle,” business goes more smoothly when the government doesn’t step in to take people’s money. As a general economic principle, if people make a voluntary decision to trade something, that is a good thing and both are better off, because otherwise why would they do it? Plus, there are a lot of historic problems with tariffs, as we’ve discussed in the past.

This is the nature of “general economic principles.” They are a distillation of insight for all places and at all times.

Economic Nationalism tends to be about “specific situations.” For example, I do not think there is any great opposition to free trade, and even free immigration, from Canada. But, we have a lot of good reasons to avoid free trade, and free immigration, from Mexico. Why is that? How are they different? Plus, there is a historical element. We might be OK with free trade with Canada today, but might not be happy about it twenty years from now. Why? Why not? Noting in “general economic principles” allows us to answer these questions. But, in the real world, there are only specific situations. General principles might help to address specific situations, but there are no “general situations.” There is only Canada in 2024; and Mexico in 2024; and China in 2024.

Good Economic Nationalism

What might “good” policies of economic nationalism look like? Summarizing some of my previous arguments, I think they would be:

An across-the-board flat Tariff, for all items from all countries, not Tariffs on specific items from specific countries. This is already part of VAT taxes in Europe. I’ve been arguing in favor of a Federal VAT, accompanied by a repeal of the Sixteenth Amendment and the elimination of the Income Tax. This Federal VAT would also apply to all imports, just as is the case for most countries today. However, I would eliminate the VAT export rebate, making the VAT more like a Flat Tax and less like a Retail Sales Tax. Economic Nationalists including Patrick Buchanan have argued for a Flat Tariff approach rather than the common item-by-item approach.

Just as the Income Tax was a 19th century innovation (essentially) that replaced the crappy 18th century system of Tariffs, as a primary revenue source, today the VAT, a 20th century innovation, can replace the crappy Income Tax.

Reduction/Elimination of Immigration, and expulsion of illegal immigrants today. What is the point of immigration? Who benefits? Some countries have been very successful (Britain and Japan) with almost no immigration. There was almost no immigration in the first fifty years of US history; and in the first century of US history, almost all the immigration came from Britain, Canada, Ireland and Germany. Mexico has sat there south of Texas all this time; but there was no significant Latin American immigration until the 1960s.

January 23, 2021: A Brief History of US Immigration

The question of “who benefits” is very simple. Employers benefit, from more labor supply, resulting in lower wages. The real fact of the matter is, many immigrants really are better workers than the Bottom 30% of US citizens. Even if they aren’t, wages can be beat down due to labor competition. The Capital/Labor ratio is skewed toward Capital. The big eras of increased legal immigration in the US, 1880s and 1960s, came after a long period of peace, prosperity and limited immigration. The result was that labor was scarce and capital was plentiful. Employers had to bid up wages for the Bottom 30%, and even hire people that they would really rather not hire — the losers, the misfits, the idiots, and all the other sorry cases you find in the Bottom 30%.

March 30, 2008: The Capital/Labor Ratio

July 24, 2011: The Capital/Labor Ratio #2: How To Create Jobs

The result was a broad middle class, and a more even distribution of income, as we saw in the 1950s and 1960s, before the most recent flood of immigration beginning with the Immigration Act of 1965. The result of this flood of immigration has been that the Bottom 30% (probably Bottom 70%) have suffered, because they get paid less. The Top 30% have benefited, because they get cheaper goods and services; and the Top 1% have done best of all, because of lower employment costs.

Expelling those possibly tens of millions of existing illegal immigrants to the US is not so hard as some people think. Mostly, they expel themselves, when the environment becomes unfriendly to them. The first thing I would do is ban illegals from all public services, including public schools, welfare programs, admissions to public facilities such as National Parks, etc. Drivers’ licenses would be banned. Then, we would ban private companies from doing business with illegals. This applies especially to longer-term contracts, where some due diligence is the norm. For example: Illegals cannot own real property. They cannot open bank accounts or brokerage accounts. They cannot rent housing. They cannot borrow money, including credit cards and auto loans. They can’t get health or auto insurance. And, of course, you can’t hire an illegal, at least for regular ongoing employment that involves payroll taxes. Some people will argue that these are basically impossible to implement; but all these industries already have substantial application processes. Today, you can’t sell a beer to someone under 21; and these regulations are actually effective.

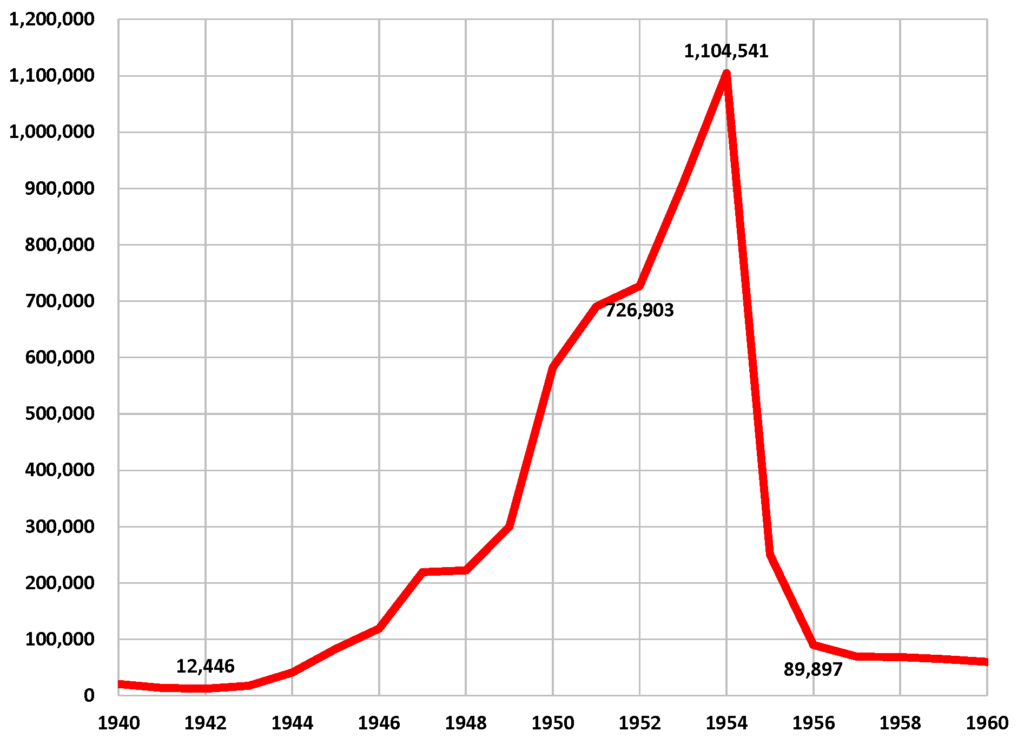

In the 1950s, there was a flood of illegal immigration from Mexico into Texas. Roughly a million Mexicans entered the US. As a result, wages for agricultural workers in Texas fell 50%. This inspired Operation Wetback, in 1954, which drove out those illegal immigrants.

This program began with 750 agents, and rose to 1600. Although many Mexicans were apprehended and deported, most of the illegal migrants left on their own, and voluntarily returned to Mexico, after finding the environment hostile in the US.

The result of such a big reduction in generally lower-skilled labor, would be a lot less supply and a lot tighter market for the Bottom 30% (especially) of US citizens. Wages would likely rise, much to the grumbling of people who hire housekeepers, gardeners, agricultural laborers and construction workers. In other words, the Upper Middle Class and Wealthy would have to pay more, and the Bottom 30% would get more, which is maybe a good thing. Many businessmen would complain that “Americans won’t do these jobs,” but of course they would, if you paid them more. Americans did them in the past, before 1965, and were mostly well paid for it.

More Capital. One way to improve the Capital/Labor ratio, in favor of Labor, is Less Labor. The other way is More Capital. More Capital basically means more investment; because there is hardly any form of new investment that does not involve new employment. I find that, despite arguments regarding the free movement of capital, those countries with high domestic investment also tend to have high domestic savings. With this in mind, I would try to eliminate all taxes on savings and capital, including especially the Capital Gains Tax, always one of the most destructive taxes, but also taxes on Interest Income and Dividends. You might add Inheritance and Gift taxes to this. All of this would be a natural outcome of a Federal VAT that eliminates the 16A and all income taxes, individual and corporate. However, differing here somewhat from Patrick Buchanan and others who have argued for the complete elimination of corporate profits taxes, I think it would be best if corporate and individual income was taxed at the same rate. This is a natural outcome of a Federal VAT, and also, usually preferred by the Flat Tax advocates who would like to see a Flat 10% or 15% rate on both employment and business income. Interest should be taxed at the corporate level, not at the individual level, known as the “VAT base.”

An alternative to this is to tax Interest and Dividend income, on distribution, at a low rate (the tax is paid by the corporation), but not to tax corporate profits. Estonia does this today. You still don’t tax Capital Gains. I think this unfairly advantages businesses, but it is not the worst thing.

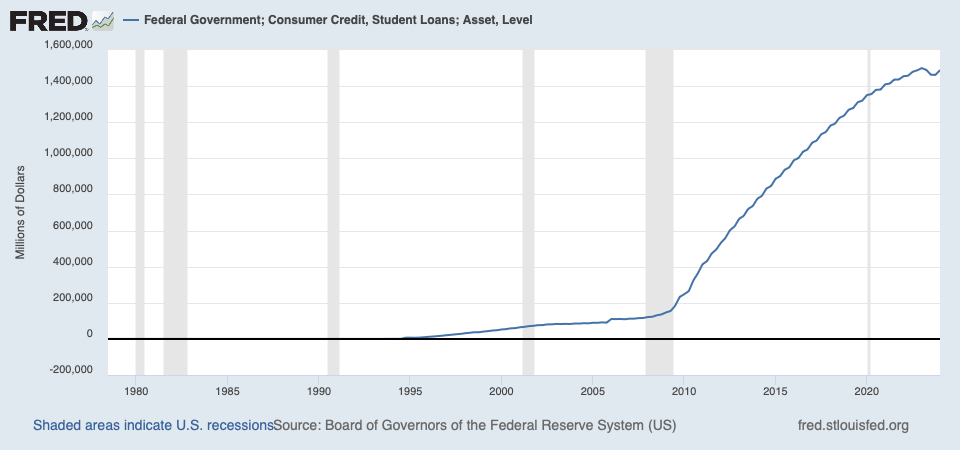

“Net Savings,” especially at the consumer level (as opposed to reinvested corporate profits), is the net result of gross savings (accumulation of financial assets) vs. gross indebtedness (accumulation of financial liabilities). There is way too much Consumer Debt these days, for low-value uses. I would even include things like Home Mortgages. I think Mortgages can be a productive use of indebtedness, but maybe not such big mortgages. In other words, houses should be cheaper.

October 22, 2017: How Much Should Homes Cost?

January 20, 2018: How Much Should Homes Cost (To Rent)?

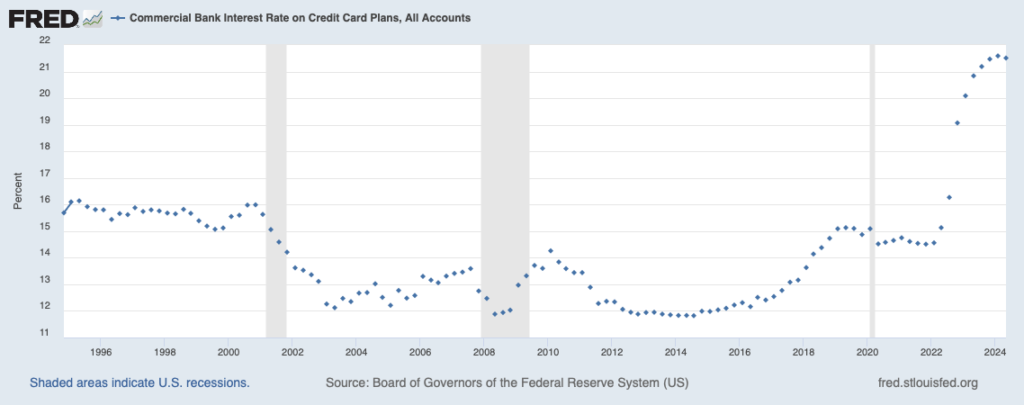

But, setting aside some of these “good” uses of consumer credit, there are a lot of “bad” uses, including credit cards and, regrettably, student loans. In general, we want people to get out of debt. In the past, States had usury laws that put a maximum interest rate of 10% on consumer lending. These had to be abandoned in the inflationary environment of the 1970s and early 1980s, but they never came back. Maybe they should.

Along with this, you might require higher monthly payments. For example, the minimum monthly payment on a credit card should be at a level that pays off the entire balance, with interest, in twelve months. Perhaps the 15yr mortgage should be the standard fixed-rate mortgage, rather than the 30yr. People would end up buying smaller houses, and paying them off faster. For many years, it was difficult for people in Mexico to get a mortgage at all. The result was that 80% of people owned their own homes, and only 13% of these had a mortgage.

I personally think that building your own home should be much more common, and easy to do. A lot of homes in the 19th century were built by their owners — a Little House on the Prairie. It is hard to build a big house, but it is not so hard to build a Little House, perhaps of 600 square feet. This would cost about $70/sf for construction materials, the owner of course providing the labor, so about $42,000 for 600sf. People added to these houses over time, producing the “multiple boxes” look of late-19th century vernacular architecture.

Here is a typical 19th century “Little Box” house, to which has been added a rear extension. The front porch was probably also added later.

You might have something similar for auto debt. For example, let’s say that you can’t borrow more than $30,000 on an auto loan. If you want a car that costs more than that, you have to pay cash on the excess above $30K. Or, I guess you could lease; which at least does not involve direct indebtedness. Some people may argue that we shouldn’t be such nannies to grownups. But, human societies have always found that the Bottom 30%, and maybe a lot more than that, tend to get into way too much debt.

While Less Labor is arguably bad for business (businessmen complain about tight labor markets and higher wages), More Capital is, arguably, good for business. It means more investment, which means, higher profits. At a more personal level, it gives businessmen something fun to do, managing all these new businesses, and hiring all these new people. This is very different than just managing the same business, but paying higher wages for Labor of lower quality, which is the effect of Less Labor alone. There might be a political tradeoff of sorts here, to make business happy with immigration restrictions and mass expulsions of illegal migrants.

Sound Money. In the past, Economic Nationalism has sometimes included arguments toward a cheapening currency, with the expectation that this would make domestic workers and industries “more competitive” due to lower prices. This was common in the 1930s, and the argument has not gone away. We are even seeing it again today, as Trump is worried that a rising dollar vs. other major currencies (euro or yen) is bad news for US employers. These forex moves are in fact a problem. But, the best answer, for the longer term, is Sound Money — a currency that does not lose value. If the Japanese yen is falling in value, for whatever reason, and you want to cheapen the dollar to maintain stability of exchange rates, the result would be that the USD would fall in value just as much as the yen.

Obviously, if we combine Sound Money with business-friendly Low Taxes, we have the Magic Formula. The Magic Formula — combined with generally high tariffs and highly restricted immigration — is what the United States actually had, throughout the 19th century, and much of the 20th.

read The Magic Formula (2019) in free .pdf format

I will continue with a discussion of “bad economic nationalism” in the future.