We’re looking into Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder (2019), by Thomas M. Humphrey and Richard Timberlake.

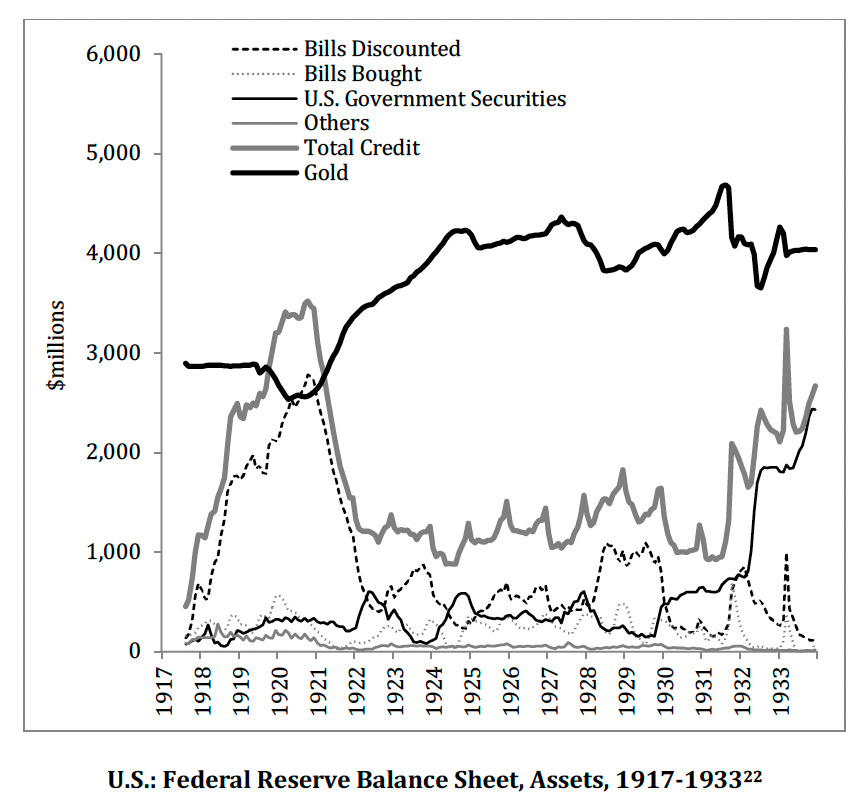

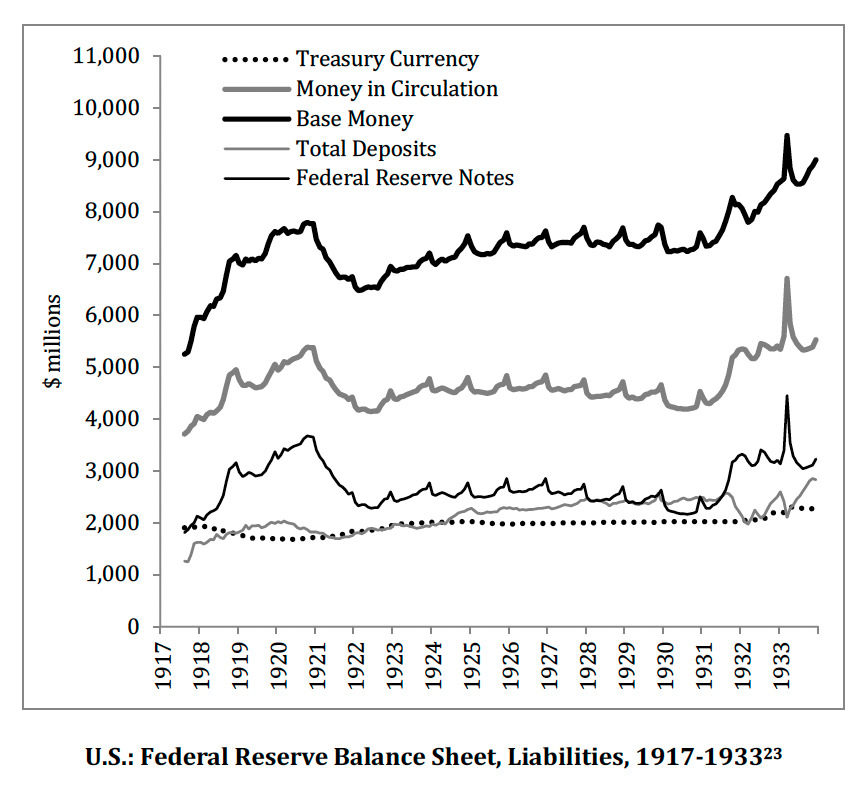

Let’s review what the Federal Reserve actually did in that time. We will look at its complete balance sheet — something that Humphrey and Timberlake never do.

January 26, 2014: The Federal Reserve in the 1930s #2: Interest Rates

January 19, 2014: The Federal Reserve in the 1930s

December 23, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 4: The Historical Record

December 16, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 3: Balance Sheet and Base Money

November 25, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 2: Interest Rates

November 18, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s

July 22, 2012: The Composition of U.S. Currency 1941-1970

July 15, 2012: The Composition of U.S. Currency 1880-1941

October 2, 2016: The Interwar Period, 1914-1944 (contains many links)

August 25, 2017: The Interwar Period #2: It’s Not That Complicated (many more links)

I also recommend that you read Chapter 6 of Gold: The Final Standard, which summarizes a lot of my investigations into the Interwar Period.

Free .pdf of Gold: The Final Standard

First of all, we can see that the Federal Reserve did not “contract” in 1929-1933. Its balance sheet, and base money, both expanded. There was a big expansion of banknotes in late 1931, in the banking panic that followed the British devaluation of September 1931. The British government bond was considered the “risk free asset” at the time, and it had a long history of reliability to justify that claim. When the British pound was devalued, the value of British government bonds — and all other pound-denominated debt — naturally plummeted by the amount of the devaluation, in terms of US dollars. Also, over twenty other countries followed Britain into devaluation by the end of the year, including Japan. This meant that all US holders of bonds denominated in all these currencies also had huge losses. No wonder there was a bank panic. People naturally thought that the US might be close behind, with a devaluation. This indeed happened, although it was still a couple years off. The US dollar was devalued in 1933, and relinked to gold in 1934.

After this big increase in banknotes, banknotes basically flatlines into 1933. There was no particular rush into “paper cash” and out of banks, except for this late-1931 period. (There was a quick rush into banknotes just before the Bank Holiday of 1933. This was reversed immediately afterward, as banknotes were re-deposited in banks.)

Before 1931, we see that banknote use actually declines, while bank reserves are flat at high levels. There is no obvious lack of bank reserves here. Bank reserves do drop dramatically in late 1931, while banknotes expand. But, this is quickly halted, and bank reserves then moves higher, as banks rebuild their reserves.

Federal Reserve Total Credit (on the Assets side of the Balance Sheet) explodes higher during the late-1931 panic. Both Bills Discounted and Bills Bought leap higher. However, there are sudden gold outflows in huge size. As the Fed lent to banks, creating money in the process, and with fears of USD devaluation swirling, the value of the USD sagged compared to its gold parity. The parity was at $20.67/oz. A higher “price of gold” meant that it took more dollars to buy an ounce of gold, showing a decline in dollar value, compared to gold. Let’s say that the market “price of gold” was $21.00. The Federal Reserve offered to either buy or sell gold at $20.67. This would make the Federal Reserve the cheapest seller of gold ($20.67 instead of $21.00), so people would buy gold from the Federal Reserve, and gold would flow out. These gold sales reduced base money, by the amount of gold sold. The reduction in base money would support the currency, thus maintaining the dollar link to gold, aka the gold standard. And indeed the USD link to gold was maintained, even through this time of financial chaos and crisis — a pretty good showing by the Fed. Well done! Thus, the Federal Reserve increased base money dramatically through bank lending, and then this was largely cancelled out by sales of gold due to a weak dollar, re-absorbing the money created through bank lending. However, the gold sales did not completely offset the expansion due to lending. Base money grew dramatically, due to the expansion of banknotes since bank reserves declined.

In 1932 there is a huge leap higher in Government Securities. The authors describe, in some detail, a conference in Chicago which recommended that the Fed experiment with a dramatic expansion in its base money supply, in light of the economic difficulties of the time. The Fed did this. In the first instance, this money creation becomes bank reserves. But banks (as a whole) did not need all this extra reserves. Discounting and lending falls, as banks pay off their loans from the Fed with their excess cash. Naturally, all this money creation –and all the concern that it created, which can be summed up as: “WTF are these guys doing?” — also led to a decline in USD value, and gold outflows. The gold outflows and the decline in discount lending largely cancelled out the huge expansion in government securities, exactly as we would expect. There was no increase in demand for base money, that accompanied this big bond-buying binge (besides the linear trend of that time), so the mechanisms of the gold standard system naturally re-absorbed all this excess money. However, the trend toward higher base money of the time did continue. The Federal Reserve was still expanding base money, at the same rate it had been earlier. Note the very smooth line of base money expansion during this time, from the beginning of 1932 to early 1933. This huge bond-buying experiment produced nary a ripple. The operating mechanisms of the gold standard matched supply with demand, while demand apparently had a smooth slope of expansion during this time.

Once the bond-buying ends, gold inflows begin again, which extends this smooth slope of base money expansion. Basically, during this time the USD is a little strong compared to gold. The “market price of gold” is perhaps at $20.00 instead of $20.67. There is demand for more dollar base money. The Federal Reserve becomes the highest bidder for gold, willing to pay $20.67 instead of $20.00. Everyone sells their gold to the Fed, and gold holdings increase. The Fed pays for this with base money creation, expanding base money.

I go into these processes in much more detail in Gold: The Monetary Polaris, so read that if this seems confusing.

Read Free .pdf of Gold: The Monetary Polaris

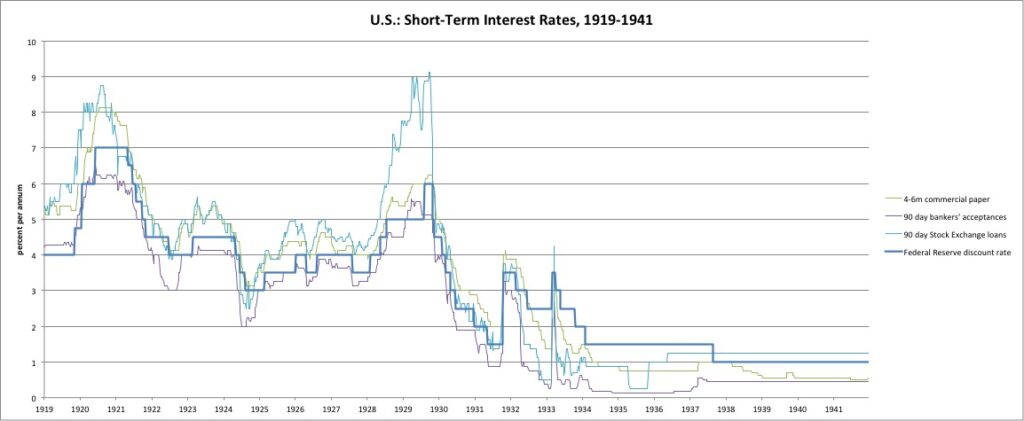

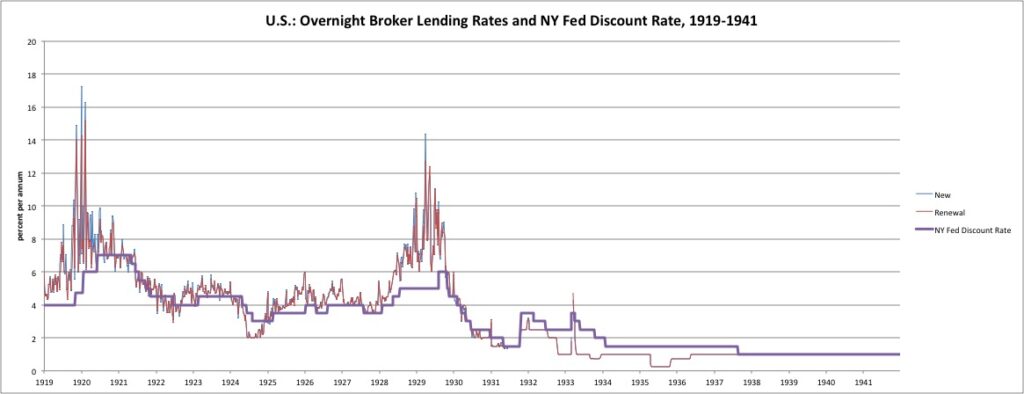

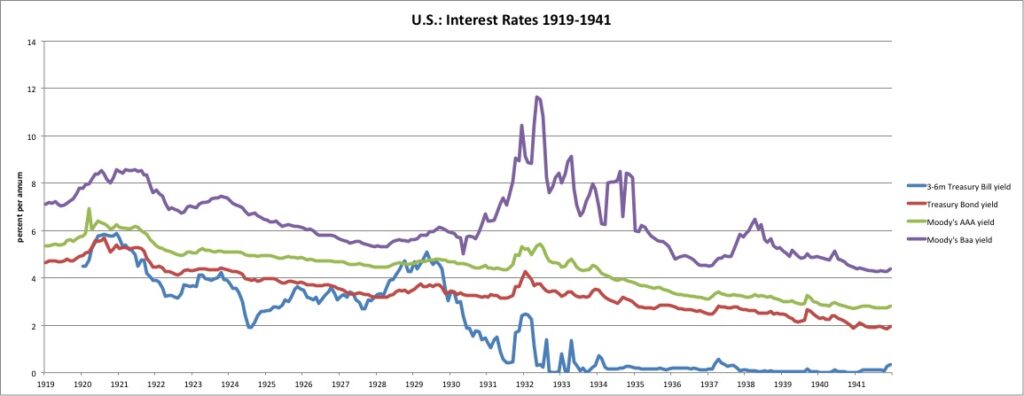

Here are interest rates of that time:

January 26, 2014: The Federal Reserve in the 1930s #2: Interest Rates

As we can see, interest rates were quite low.

The Federal Reserve was set up in response to the Panic of 1907. The Panic of 1907 was a “liquidity shortage crisis.” There was a short-term shortage of base money. All the banks wanted to borrow, and nobody had money to lend. There was no particular solvency crisis. Outside of the financial system, the economy was basically fine. The result was that short-term interest rates soared to very high levels, over 100% per annum. The Federal Reserve was created to be able to act as a “Lender of Last Resort” in these situations, increasing the overall quantity of base money. Thus, the Federal Reserve was concerned with “systemic,” or system-wide, shortages of base money (bank reserves, cash or “liquidity”), characterized by super-high interest rates even for good borrowers, not shortages at individual banks that arise from fears of insolvency. Let’s say there’s a bank run at Bank A, because people think Bank A could be insolvent. People withdraw their cash, and deposit it in Bank B. Bank A now has a shortage of bank reserves, and Bank B has a surplus. There is no “systemic” shortage of reserves. Interest rates on good credits remain low. However, nobody lends money to Bank A because of the risk of default.

Although there were many, many banks that suffered from individual “liquidity shortage crises” due to fears (warranted or not) of insolvency, there were also many banks that enjoyed a surplus of liquidity, as worried depositors moved from Bank A to Bank B. (Note that, in 1930-31, overall bank reserves remain at a high level. For every withdrawal from one bank, there was a deposit in another.) Since Bank B now has a surplus of funds, it is willing to loan out its funds at a low interest rate (which we observe), to what is perceived as a good credit — not Bank A.

Also, unlike 1907, the economy as a whole was definitely not doing well, and there were fears for the ability of end borrowers to pay back their loans to the banks.

From this, we can see why the Federal Reserve did what they did. By all appearances, there was plenty of base money. Every time they tried to add more, via some kind of credit expansion, the value of the dollar would sag vs. gold, and there would be gold outflows that cancelled out the credit expansion. Interest rates among good borrowers were low. There was no shortage of funds to borrow, for good borrowers. The Federal Reserve was not responsible for the bad business decisions of certain banks. That would be a form of political favoritism — making loans to entities that no profit-motivated banker would loan to.

The authors talk about “eligible paper,” or short-term lending assets of banks. The Federal Reserve apparently refused the eligible paper of some troubled banks. But, why couldn’t these banks sell their eligible paper to another bank? All banks were in that business. If the credit was good, and the interest rate was attractive (not very hard in a low-interest-rate environment), then what was the problem? Why should the Fed take it, but nobody else? Probably, other banks did take “eligible paper.” This means one of two things: a) Bank B outright purchased the bill of a third-party, such as a corporation; or b) Bank B lent against the bill of a third party as collateral. If the third party was sound (let’s say they were), then why wouldn’t Bank B do this, even if Bank A had solvency issues? And since Bank A was in trouble, they would probably offer a pretty good price to Bank B. In the first case, Bank B owns the paper directly, paying cash for it to Bank A, and Bank A is out of the loop. In the second, the loan is directly collateralized. Probably what happened is, the various Bank As that were suffering deposit outflows, actually did sell all their eligible paper to the various Bank Bs. Why wouldn’t they? Why wouldn’t the Bank Bs take it? Of course, the total amount of eligible paper doesn’t change. It just moves from Bank A to Bank B. But Bank B doesn’t need to discount this with the Fed. It already has plenty of cash.

In retrospect, we can see that, in the midst of crisis, maybe the Federal Reserve should have indeed made loans to some troubled banks without much concern for their solvency. But that is not how the Federal Reserve saw its role at the time. The Federal Reserve was supposed to: A) Maintain the gold standard system, including by not expanding the monetary base so much that the value of the USD declined vs. gold. This was accomplished via gold conversion (outflows), if by no other means. B) Respond to any “short-term systemic liquidity shortage crisis,” identified by a shortage of funds to lend to high-quality borrowers, and thus very high interest rates (10%+) for high-quality borrowers. The Federal Reserve did this very well, in the midst of crisis.

To wrap things up for this week, here is a nice description of Monetarism and Milton Friedman from Murray Rothbard.

“Milton Friedman Unraveled,” by Murray Rothbard (2002)

Rothbard makes the basic point that I made earlier, which is that Monetarism is a form of “Mercantilism,” or macroeconomic manipulation via floating fiat currencies, not a “Classical” doctrine of neutral, unchanging Stable Money. Rothbard himself didn’t escape the “Prices/Interest/Money Box” that characterized the “Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle,” blaming Benjamin Strong for what amounts to nothing important. But, Rothbard’s criticisms of Friedman are about right, in my view.

The point here is, whenever you get Monetarists, in their discussions of the Great Depression, it always amounts to a stack of rationalizations to justify Mercantilist floating-fiat monetary manipulation. Basically, it is more money creation — a lot more — which of course would lead to the end of the gold standard and a big decline in currency value, and a floating currency thereafter.

…