We’re looking into Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder (2019), by Thomas M. Humphrey and Richard Timberlake.

September 17, 2023: Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed #2: Let’s Review

Normally, in good times, a bank might have some kind of problem. My own father worked for a Big Eight (later Big Six and then Big Four) accounting firm in Los Angeles in the 1980s. One of his clients was a small Savings and Loan whose customer base was largely Chinese immigrants. A rumor got out that this bank, Bank A, was in trouble. Not knowing about US banking regulations including deposit insurance, these Chinese immigrants rushed to Bank A to withdraw their deposits, and then transfer them to nearby neighborhood bank Bank B.

In fact S&Ls did have long-term festering problems in those days, which began in the 1970s and were not finally resolved until the early 1990s. So, maybe this rumor had some truth to it. But, basically, Bank A was fine. It was solvent. Its assets (loans) were in good shape. The overall economy was fine. The president of Bank A contacted Bank B, where everyone was moving their funds to from Bank A. Bank B loaned the money back to Bank A. The money just went in a circle. Bank B was very happy to make interest income by lending to Bank A. Bank A was fine, and after a while, the bank panic dissipated. Nobody needed to borrow from the Federal Reserve. There was a “shortage of liquidity” at Bank A, and a “surplus of liquidity” at Bank B, which was resolved by Bank B loaning the funds back to Bank A. There was no “systemic” (system-wide, total base money supply) liquidity shortage.

However, the banking crisis of the 1929-1933 period took on a “systemic” character. This was not a “systemic” liquidity shortage crisis, but a solvency crisis, which then tended to cause more solvency crises.

For example, let’s say you are a business. You have a checking account at a bank, Bank A, that you use to pay suppliers and payroll. Bank A shuts down. You are locked out of your checking account — even if your business is fine and completely healthy. Now this business itself might default on its borrowing, and commitments to employees and other obligations. In normal times, a business like this could probably get a loan from another bank. But in the atmosphere of general crisis, banks don’t want to make any more loans. Now the business defaults — creating a solvency crisis for another bank. The same could apply to individuals. They are locked out of their banks, and miss payments on their mortgage as a result. Or maybe their bank is fine, but their employer can’t make payroll because their bank shuts down, and now they miss the rent, which throws their landlord into crisis. What a mess.

In the middle of crisis, “solvency” is hard to determine. A bank is solvent if its long-term borrowers are able to pay their debts. If borrowers can’t pay debts, then the bank may be “insolvent.” But this requires estimates of long-term ability to pay. Also, you might have perfectly good credits, that end up defaulting anyway, like the example in the paragraph above. And who the heck knows the condition of all of a bank’s borrowers, outside of the bank itself? No wonder nobody wanted to lend to troubled banks. They would be afraid of getting stuck on the list of creditors in bankruptcy court. And so, unable to continue paying out for deposit withdrawals, the bank would shut down.

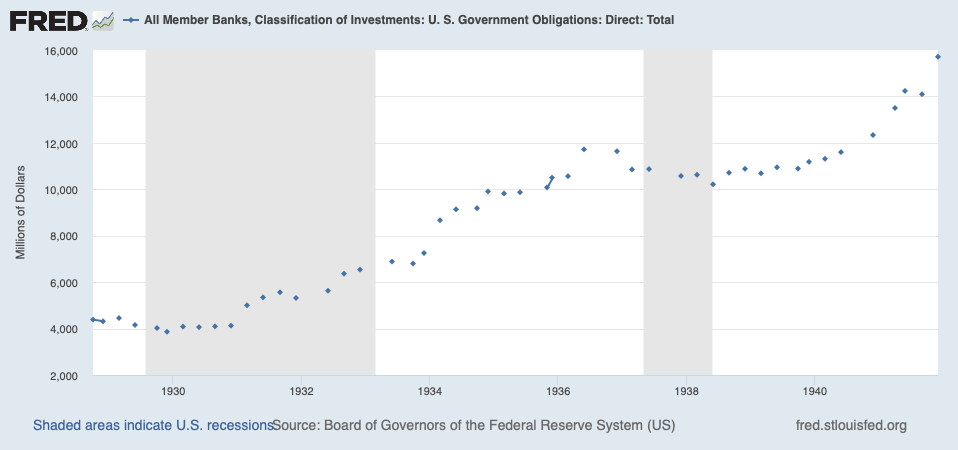

First, let’s note that this has nothing to do with: A) The gold standard, which means maintaining a stable value for the currency (vs. gold); or B) A “systemic liquidity crisis” in the 1907 model, for which the Fed was created — characterized by very high short-term interest rates for otherwise solvent borrowers. It is a solvency crisis, not a liquidity crisis, or a currency crisis (where the value of the currency departs from its gold parity). This didn’t really have anything to do with the Fed, which is exactly what the Fed (and other major central banks including the Bank of England) said at the time. The Fed observed that: A) The dollar was worth its promised parity with gold; and B) There was no evidence of a systemic shortage of base money, characterized by very high interest rates. Healthy banks told the Fed they had plenty of money to lend — to good borrowers. Mostly, they bought government bonds — instead of selling government bonds, which is what you do when you need to raise cash.

Did the troubled banks suffering deposit outflows sell all their government bonds? Of course they did. The depositors then took their money to the healthy Bank B, and Bank B bought government bonds with the new money.

Nevertheless, this “systemic solvency crisis,” where there is a sort of systemic breakdown that throws otherwise healthy borrowers into crisis, was certainly a characteristic of the Great Depression.

The Federal Government (not the Fed) responded to this in two ways. The first was the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, introduced in 1931. The second was the Bank Holiday and introduction of Deposit Insurance, in 1933. The first was partially successful, and the second was completely successful.

Wikipedia on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

The project began in January 1932, and loaned out $1.5 billion in 1932. It loaned out more in 1933 and 1934, but maybe that is not so important since Deposit Insurance had been introduced by then.

In February 1932, the Federal Reserve held about $3.15 billion in gold. (The Federal Reserve’s “balance sheet” aggregates the whole monetary system of the time, which also included National Banks and Treasury Gold Certificates, aka “Treasury Currency” of about $2 billion, so the total gold was more like $4 billion.) Theoretically, it could have replaced all this gold with discount lending. What would have happened is that, the new base money created by lending would tend to create outflows of gold to compensate, resulting in no change of base money. So, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet would show +$2 billion (let’s say) of Discount Lending, and a -$2 billion outflow of gold bullion. This might help troubled banks, but it would be a rather bad look, and very justifiably lead to concerns that the Fed was in the process of basically abandoning the gold standard. This could lead to various forms of panic — which we actually saw in 1933, and which led directly to the Bank Holiday and dollar devaluation that year. Similar acts by central banks — in Japan in 1931, and France in 1936 — where central banks had big increases in lending leading to offsetting gold outflows, directly preceded devaluations in both cases. A similar pattern, although much smaller, was also seen in the British devaluation of 1931. So you can imagine what the market would have thought about the Fed going down that path. The Fed probably had a similar opinion, which is why they didn’t go down that path.

There is a lot of talk about “excess gold,” held by the Federal Reserve in excess of statutory reserve requirements. In February 1932, this was $1.38 billion. So, the Federal Reserve could have had additional discount lending of about that much, leading to gold outflows of about that much. But, that is about the amount that the RFC, which was created for exactly this purpose, really did lend out in 1932, so what was the problem?

The Banking Act of 1933 introduced Federal deposit insurance, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which is still active and important today.

Wikipedia on the Banking Act of 1933.

The introduction of Deposit Insurance was preceded by the Emergency Banking Act of 1933, which produced the Bank Holiday of 1933.

Wikipedia on the Emergency Banking Act of 1933

Now we have a response to bank solvency, or the perception of bank solvency. During the bank shutdown, Federal inspectors performed triage on troubled banks. Some were shut down. Those that reopened had received a Federal stamp of approval, which naturally reduced fears. Rather than withdrawing cash from banks when they reopened, depositors took the paper banknotes they had received, and deposited them back in banks. In the week following the reopening, $1 billion of banknotes (out of about $5 billion total) were returned to banks.

Next week, we will talk a little about the FDIC, deposit insurance and how these things are dealt with today. Until then, feel free to do some homework by studying the How Banks Work series.

So we see that the RFC really did what people claim the Federal Reserve should have done — although it had nothing to do with the Fed’s mandate to keep the value of the currency linked to gold, and address systemic liquidity-shortage issues, and was actually directly contrary to Fed principles at the time. Combined with the Emergency Banking Act and, soon after, Deposit Insurance, an effective solution to systemic insolvency fears was found.

As I go through all this explanation, remember that I am basically describing things the same way that the people at the Federal Reserve also described it. Their actions at the time make perfect sense, according to this description. I am not making up something new that I invented while sitting on the potty, that somehow nobody noticed in the last 90 years, including other bankers and the people working at the Federal Reserve at the time — which is what most economists claim.

The basic problem here is that these authors are confused (let’s be generous) by Monetarist nonsense. Go find some authors that are not confused. Remember, Monetarism is a “Mercantilist” doctrine of macroeconomic manipulation via floating fiat currencies.

Chapter 6: The Quantity Theory Alternative

A singular curiosity marks the early history of the Federal Reserve. In the 1920s and the early 1930s, when U.S. gold holdings were sufficiently large to relax the constraint of the international gold standard and allow domestic control of the money stock and price level, the Fed deliberately shunned the best empirical policy framework that mainstream monetary science had to offer.

Developed by Irving Fischer and other quantity theorists, … the quantity theory framework had by the mid-1920s progressed to the point where, statistically and analytically, it was the state of the art in policy analysis. … Here, ready made, seemed to be the answer to a central banker’s prayers. Here was a framework the Fed could use to conduct policy and stabilize the economy.

Yet the Fed … refused to have anything to do with this framework and its components. (p. 57)

As is typical for books of this type, it consists of a pile of justifications about why the Federal Reserve, which very sensibly did not want anything to do with this floating-fiat garbage, had made a big mistake.

Should the Federal Reserve made more loans to banks of questionable solvency, even though this contravened the operating principles of the time, which was that the Fed wasn’t going to play favorites? Especially in the time before the RFC was begun in 1932? Probably. And in fact there was an explosion of discount lending in 1931, with the Fed doing exactly what these people claim the Fed should have done. But the real lasting and effective solution was Deposit Insurance in 1933. Since we are playing make-believe, and accusing the Federal Reserve of not doing something that we only today expect them to do because of the Great Depression, why don’t we just play a different make-believe and say that Herbert Hoover should have introduced the RFC and the FDIC/Deposit Insurance in 1930, instead of Roosevelt in 1933?