Chapter 6 in The Gold Standard: Retrospect and Prospect is a paper by Lawrence White, “Arguments Against the Gold Standard.”

This too is a worthy topic. I will try not to go too long with commentary here, since White lists 14 claims, each of which would make the good topic of a website item (and in most cases I have written about them). Plus, we have not only the claims themselves, but also White’s responses, which deserve comment. Perhaps we will return to this paper sometime, whenever I feel like I need something to talk about.

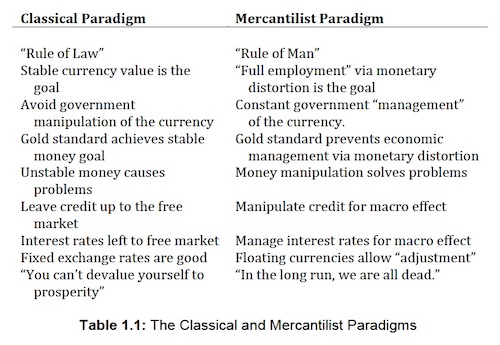

Credible arguments against the gold standard really boil down to two: First, that gold did not serve its role as an adequately stable Standard of Value. There isn’t much evidence of this. It seems to have worked pretty well. Second, that having a Stable Standard of Value, in other words the Hard Money or Classical Paradigm, is not a desirable goal. In other words, arguments in favor of a Soft Money or Mercantilist money-manipulation inflationist doctrine. There isn’t much evidence anywhere that this produces any lasting advantages, but that doesn’t stop people from arguing on its behalf.

That is pretty much the whole conversation that you need to have. Have I left anything out?

When we look at the history of all of the world economy using the gold standard, it looks pretty good. The United States embraced the principle of the gold standard for nearly 200 years, from 1789 to 1971, and became the wealthiest and most prosperous country in the world. Britain used the gold standard for longer than that, and ended up not only being the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, but also, master of the world’s largest empire. The last decade of the gold standard, the 1960s, was perhaps the most prosperous decade since 1913. The gold standard, in its Bretton Woods form, seemed to be working rather well, which is why all the world’s governments wanted to keep it, even the US President Richard Nixon and Fed Chairman Arthur Burns.

Thus, it is rather odd that many people today think the gold standard is silly. Nothing that is so widely embraced, for so long, and that produces such good results, is silly. What’s silly is the odd notions that they have in their head about what a gold standard system was or could be, which have little relation to history or reality. Unfortunately, this has been as true of the remaining gold standard advocates as it is for the mass of fiat-currency-loving academics. We have had many decades of the gold standard advocates themselves also spouting stuff that isn’t true. One of the most egregious was Murray Rothbard, with his “100% reserve” notions, “fractional reserve banking” nonsense, and the idea that, to implement a gold standard, the currency would have to be devalued by about a factor of 10. We end up with a muddle, with nothing very worthwhile on either side of the debate.

Claim #1: There isn’t enough gold to operate a gold standard today.

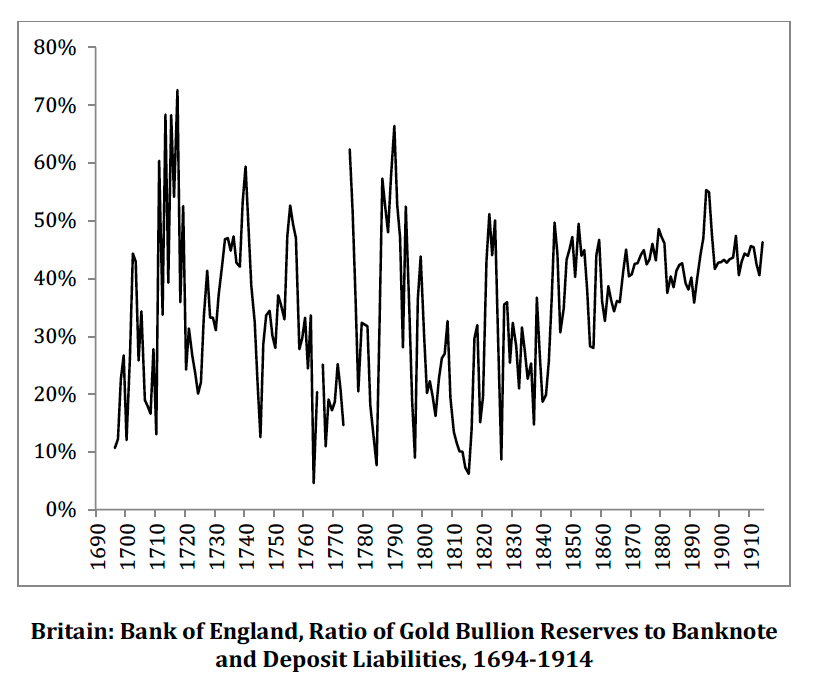

There is actually about 6 times more aboveground gold in the world today than there was in 1910. More than half of this was mined after 1971. We don’t have to hold very large amounts of gold in vaults. The idea is simply to maintain the value of the currency at the gold parity, which could conceivably be done without any gold reserves at all. For example, money market funds today keep the value of their shares at $1, even though they don’t actually hold any dollars — base money including banknotes or a deposit at the Federal Reserve. Their holdings are 100% debt instruments. Euro-linked currency boards today do not actually have any euros — banknotes or ECB deposits. They have government bonds and maybe some commercial bank deposits. But, their currencies maintain their fixed EUR parity with perfect reliability and unlimited conversion (you can trade the domestic currency for euros with the issuing central bank). White correctly notes that the reserve coverage of money-issuing organizations (could be a crypto stablecoin) does not need to be 100%, or 30% or even 10%.

Claim #2: The Gold Standard is an Example of Price-Fixing by Government. This is really dumb. White gives a quote from Barry Eichengreen:

But the idea that government should legislate the price of a particular commodity, be it gold, milk or gasoline, sits uneasily with conservative Republicanism’s commitment to letting market forces work, much less with Tea Party–esque libertarianism. Surely a believer in the free market would argue that if there is an increase in the demand for gold, whatever the reason, then the price should be allowed to rise, giving the gold-mining industry an incentive to produce more, eventually bringing that price back down. Thus, the notion that the U.S. government should peg the price, as in gold standards past, is curious at the least.

The idea of a gold standard is that the value of the currency is tied to gold, in much the same way as more than half of all countries worldwide tie their currencies to some external standard, usually the dollar or euro. So, even if someone doesn’t like gold much, they should be familiar with the concept. Eichengreen is either a total idiot (which I doubt), or, like Milton Friedman who used similar arguments, and who also wasn’t a total idiot, is intentionally strewing nonsense to confuse ignoramuses. White’s answer here is pretty good.

Claim #3: The Volatility of the Price of Gold Since 1971 Shows That Gold Would Be An Unstable Monetary Standard.

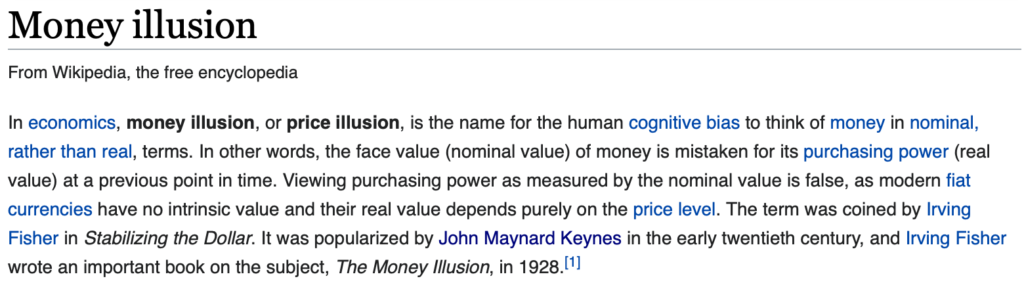

This is basically the “money illusion.”

How do you know that gold is going up and down? If gold were perfectly stable in value (it’s not but let’s assume), the variation in the dollar/gold exchange rate would be entirely a result of the dollar going up and down in value. After all, the whole principle of a gold standard is that gold is stable in value; a principle proven over centuries of experience. The whole principle of a floating fiat dollar is that its value goes up and down, according to the whims of ever-changing central bank policy. You could argue that gold, for some reason, is less stable in value today than it was during the long centuries of the world gold standard. But, you would have to come with some evidence. How do we know that it isn’t just the dollar itself going up and down? If gold really was perfectly stable in value since 1971, if it really was beyond all reproach, would the arguments of these critics change in any way? Would they be able to perceive that fact? Or is it just Money Illusion?

Not surprisingly, nobody involved here seems even to ask this question, much less answer it. This includes the luminaries cited by White: Eichengreen, James Hamilton of the University of California, and Tyler Cowen. Either they are befuddled by the Money Illusion themselves, or, being not quite this dumb, want to intentionally befuddle others. White’s answer here is not bad, but also makes no mention of the “money illusion” or related arguments.

Claim #4: The Fed Must Vary Interest Rates to Peg the Price of Gold, and Doing So Would Destabilize the Economy

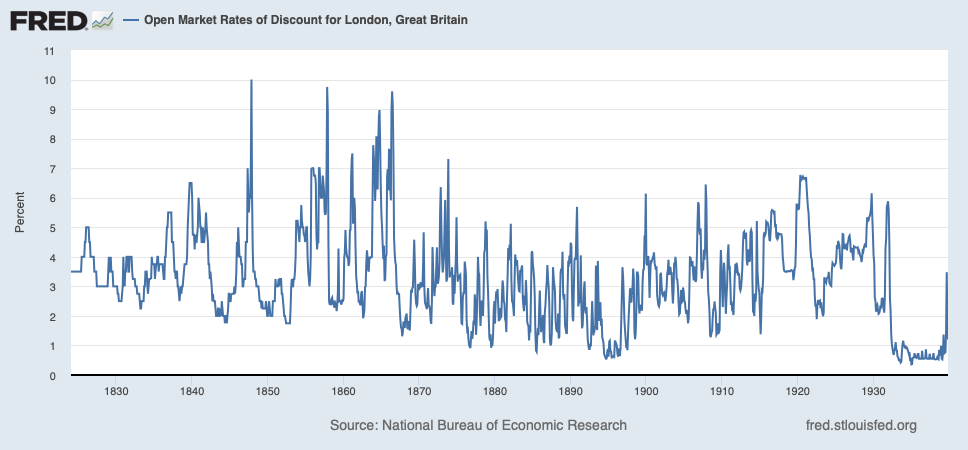

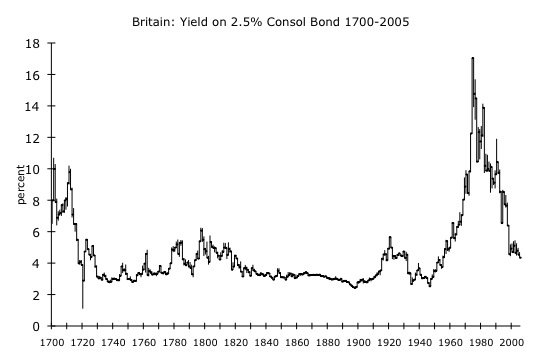

This is also rather stupid, as White correctly notes. We have hundreds of years of data of interest rates during the gold standard era. For example, here is the market rate of discount (basically, a short-term commercial lending rate) in London for 1824 to 1939:

In those days, short-term lending rates were much more volatile. The Bank of England began to act as a systematic “lender of last resort,” somewhat damping interest rates, after the Overend and Gurney crisis of 1866. But, they didn’t have an interest-rate-manipulation target as we have become accustomed to today. Instead of the short rate being fixed and the long rate being variable, in those days, the short rate was typically variable and the long rate was very stable.

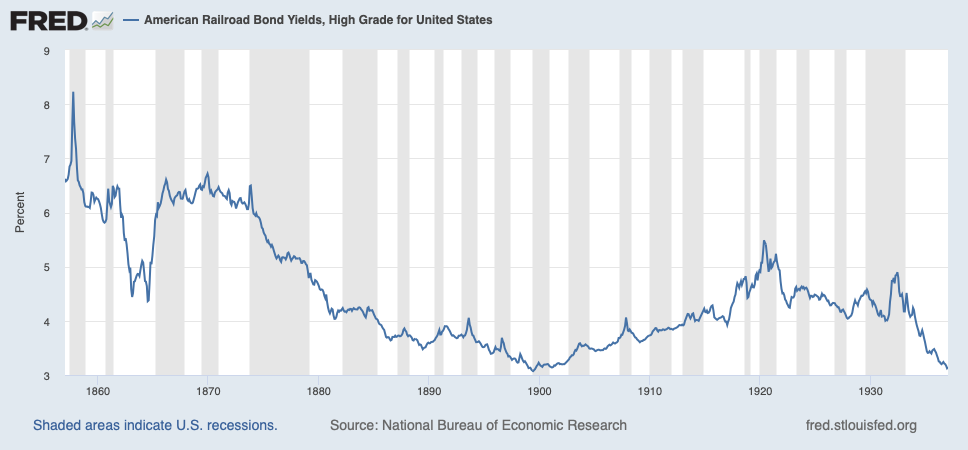

Here are some railroad bonds. Remember, the US did not return to a gold standard, after floating during the Civil War, until 1879.

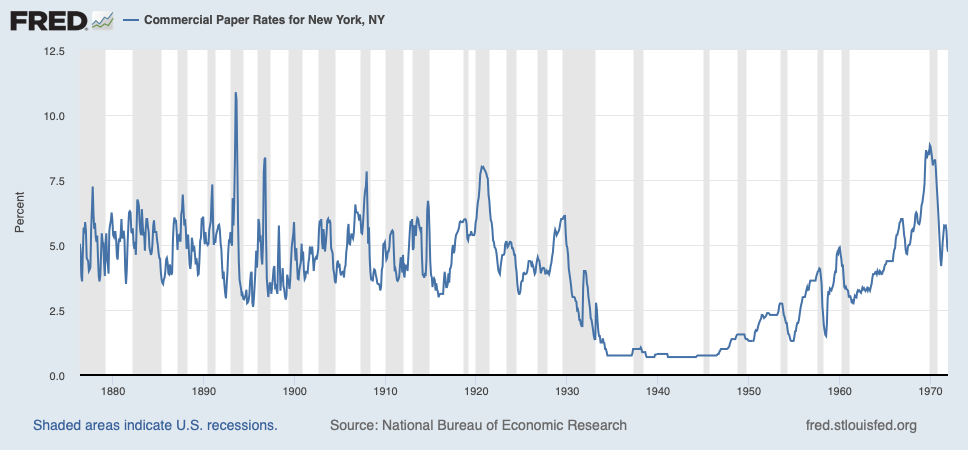

Here are commercial paper rates. These are shorter maturities, probably less than one year, and of course there is a credit premium included. Again, we see a tendency for short rates to be above long rates. This naturally drove maturity preferences: A corporation would rather finance at long maturities, getting both a lower rate and also less turnover risk. Thus, anyone who was in the short-term market tended to be lower-quality credits, reflected in a higher yield. Also, this volatility in short-term rates didn’t affect that many people, because there wasn’t as much volume at short maturities instead of long maturities. So, we shouldn’t compare to present-day conditions. In practice, it worked very well.

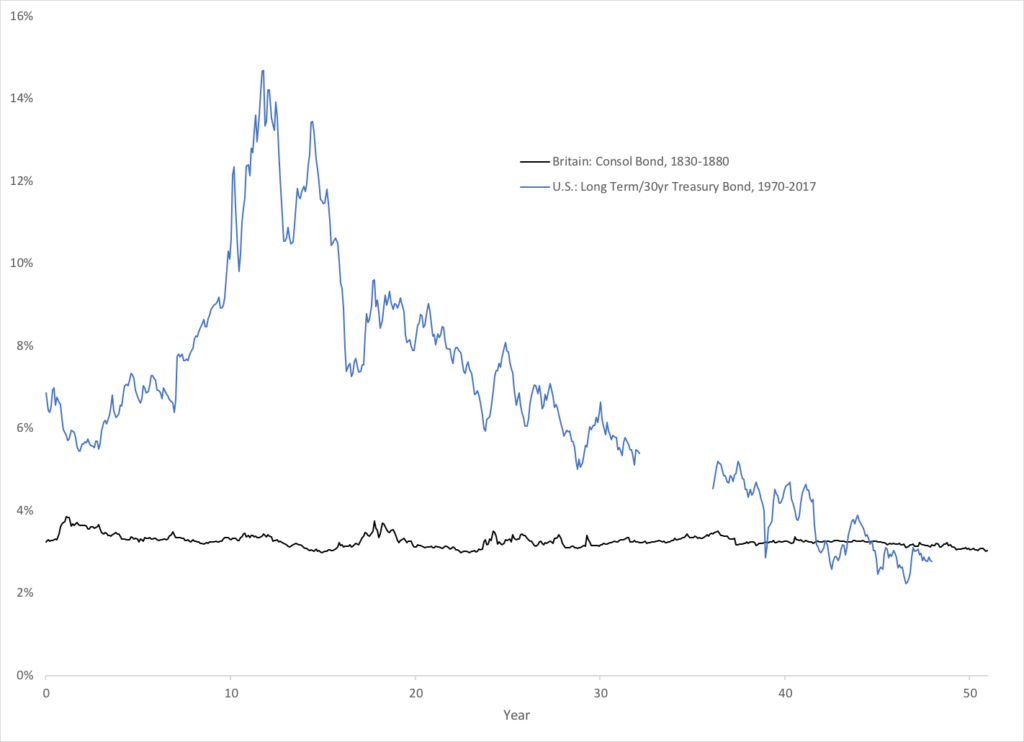

These statistics have a lot of foreshortening to them — a decade fits in an inch — making them look visually more volatile than they really were. Here is a direct comparison of fifty years of bond market volatility.

White brings up a few other points, but let’s skip ahead to Claims #8 and #9.

Claim #8&9: The Gold Standard Was Responsible for the Deflation That Ushered in the Great Depression in the United States

Unfortunately, the discussion here is rather a mess all around. Rather than defending the gold standard, which is not that hard to do — in the end, it amounts to arguing that gold adequately served its role as a benchmark of Stable Value, which is by far the majority opinion among economists — White instead veers off into the usual weeds. This is why I said that the gold standard guys have become “their own worst enemies.”

June 19, 2014: Explaining “Freaky Friday” — How The Gold Guys Became Their Own Worst Enemies

I looked into all these claims in detail, and found that most of them amounted to nothing.

October 2, 2016: The Interwar Period

August 25, 2016: The Interwar Period #2: It’s Not That Complicated

A summary is included in Gold: The Final Standard, chapter 6.

Click here for a free .pdf version of Gold: The Final Standard

To this extensive amount of material I will add one point, which I suppose should be a separate piece. That is, there is a sense today that the Federal Reserve, during 1930-1932, should have made direct loans (discount lending) to troubled banks, to relieve their individual liquidity difficulties, even though there was no evidence of an overall liquidity shortage. This is rarely expressed coherently, but it seems to be a recurring theme.

The Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England in the 19th century, wanted to avoid “systemic” or overall shortages of base money caused by short-term issues. This was the “lender of last resort,” and it was characterized by very high short-term interest rates as was the case in 1907, when overnight rates went over 100%. However, it was a principle of Fed operation that the Fed would not directly support banks that were insolvent. If there was no system-wide shortage of money, then some other bank could loan the troubled bank money, based on a free-market judgement of the bank’s ability to pay the loan back, i.e., its solvency.

This is not a bad principle, but today we recognize that in a major financial crisis like 1930-1932, it is hard to make judgements about a bank’s solvency, and many banks that are actually OK might be deprived of funds by terrified bankers, leading to economy-wide problems. Or, maybe the bank really is insolvent, but we want to wait a bit and go through the insolvency process in an organized fashion when things have calmed down, possibly years later. A similar set of arguments led to the introduction of deposit insurance, in 1933. Also, there was the 1933 Bank Holiday, where all commercial banks were examined for their solvency, and insolvent banks were worked out in an organized fashion — a good idea, it seems to me. I tend to agree with these principles, but the Fed’s policy at the time was that it wasn’t going to play favorites and bail out failed businessmen. It was only responsible for the money supply as a whole, and bankers themselves could figure out whether other bankers qualified for a loan. Overnight lending rates were low in 1930-33, showing no systemic shortage of base money, so any bank that was solvent should have been able to go to the money market and borrow at very low rates.

July 22, 2012: Europe, It’s Time For Your Bank Holiday

June 25, 2015: Greece: Planning the Bank Holiday

So, I think that we can recognize that the conditions of the time led to some new insights, just as was the case for deposit insurance.

This wasn’t really “monetary,” and didn’t have anything to do with the gold standard, which is just the value of the currency. For example, Congress could have borrowed $10 billion by issuing government bonds, and then loaned this $10 billion to troubled banks. This is basically what is done with Deposit Insurance, and the activities of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation which organizes the workout of insolvent banks today, and which has nothing to do with the Fed. The FDIC organized the workout of hundreds of insolvent banks after 2008 including the giant Citibank. Admittedly, this probably would have taken too much time, but we can see that it is a matter of “bailing out” individual banks, not the “money supply” as a whole.

Claim #10: A Gold Standard, Like Any Fixed-Exchange Rate System, Is Vulnerable to Speculative Attacks

The basic problem here is what I called Currency Option 1 and Currency Option 3, in Gold: The Final Standard, quoting Milton Friedman and Robert Mundell along the way. Currency boards, which are definitely a fixed-exchange rate system, rarely come under “speculative attack,” and do not fail when occasionally they do. Steve Hanke, a currency board expert, has found not one example of failure in the last 150 years — not even, to use an example that he likes, a currency board operated by White Russian forces during the Russian Civil War that shortly followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The White side lost, but the currency board was OK. So, when you know what you are doing, it is not a problem.

White does not make this argument, but instead argues that a distributed “free banking” system would solve this problem. This is not wrong, since Currency Option 3 comes about largely because a monopoly central bank starts to get involved in discretionary money manipulation of the macroeconomy, which comes into conflict with the fixed-value policy. Participants in a distributed “free market” model (for example a dozen private competitive crypto “stablecoins” linked to gold) are not likely to do that. For one thing, it is not credible that playing games with their currency will have any meaningful macroeconomic effect. For another, if it tried it, it would probably soon lose market share to more reliable competitors. So, this is a good answer, but it nevertheless avoids the central topic.

This is a very important point, because no matter how much we might like to have a gold standard system, we can’t have one if the people in charge of maintaining it are incompetents, and it blows up. That’s why I wrote a whole book about how to do it, Gold: The Monetary Polaris.

July 7, 2011: The Trauma of Bretton Woods

Claim #12: Setting the New Gold Parity Is Too Hard

You hear this a lot. I think it is silly. The whole world left the gold standard during World War I, and then got back on in the 1920s, without any major difficulties. The whole world left it again in World War II, and then got back on in the late 1940s, possibly with a number of adjustments in the early process. We have done this many times. The US stabilized the dollar around $350/oz. during the 1980s and 1990s (the “Greenspan gold standard”), and again briefly in 2013-2019 around $1250/oz. (the “Yellen gold standard”), and maybe again recently around $1800/oz. You just try, and probably it will be fine. If it is not fine, you can make an adjustment.

The main contention around “setting a new gold parity” is that there have been some goofballs that have taken the Murray Rothbard line that the correct gold parity has something to do with M2 and the existing gold reserves of the US government, which produces a parity value typically around 10x higher (a 10:1 devaluation) compared to the USD’s present value vs. gold. This is very stupid. No country did anything like this, when all the countries in the world went back to the gold standard from floating currencies in the 1920s and 1940s.

The other main contention is the question of “setting the value too high,” imitating the British return to gold in 1925 at the prewar parity. I don’t think this was such a big deal economically — it was a 10% change in exchange rates, which you would think would seem rather minor to people today who have lived all their lives with much larger exchange-rate swings than that — and entirely justifiable to maintain long-term currency reliability. The US did the same thing, in 1919 and in 1951, and it was fine (although it did contribute to a recession in 1921). However, Winston Churchill suffered a lot of political criticism for this — I think from a popular press that was controlled by interests that wanted to push Britain off the gold standard, as Keynes loudly advocated at the time, and which was accomplished in 1931.

Both of the recent “informal gold standards,” the “Greenspan gold standard,” and the “Yellen gold standard,” were cases of “setting the parity too high.” But, we got by, and it was fine.

At this point, to address these mostly political issues, I think it would be worthwhile to set a new gold standard parity a little low (i.e. “higher price of gold”). For example, today, if we set a new USD/gold parity at a round $2000/oz., we could not have any criticism that the value was too high (“low price of gold”) and thus “deflationary.” Against this, we might have a little more “inflation” than we otherwise would — hardly noticeable, compared to the amount of “inflation” that people have regularly experienced in recent decades. But, the advantages of having a new gold standard system, and avoiding any conflict in the early stages, would make that the most prudent course in my opinion. (White mentions the same thing.)

In Gold: The Monetary Polaris, I stated that countries have returned to gold, after a period of floating currencies, in three ways:

- Adopt a prior parity, for example after a wartime inflation. This is possible when the currency’s value has not fallen much compared to the prior parity, and when perhaps not much time has passed since the prior parity was in use.

- Adopt a parity near the present market exchange rates between the currency and gold

- A hyperinflationary situation where the currency becomes completely nonviable, in which case you can adopt any parity you like for a new system.

Among these three choices, #1 and #3 are not appropriate today, leaving #2. That wasn’t very hard, was it?

White gets into many convoluted arguments which make this seem like it is a lot more difficult than it is.

March 19, 2017: The Value of Gold Since 1971

March 26, 2017: The Value of Gold Since 1971 #2: The Dramatic Peak in 1980

We’ll skip Claim #13, bringing us to:

Claim #14: A Gold Standard Needs to be International, and the Rest of the World Won’t Come Along

Unquestionably, a gold standard is much more of an advantage when everybody is using it, so that exchange rates are fixed. This was the normal state of world affairs, from centuries previous to 1971. Even in the Medieval period, gold coins from many countries circulated throughout Europe.

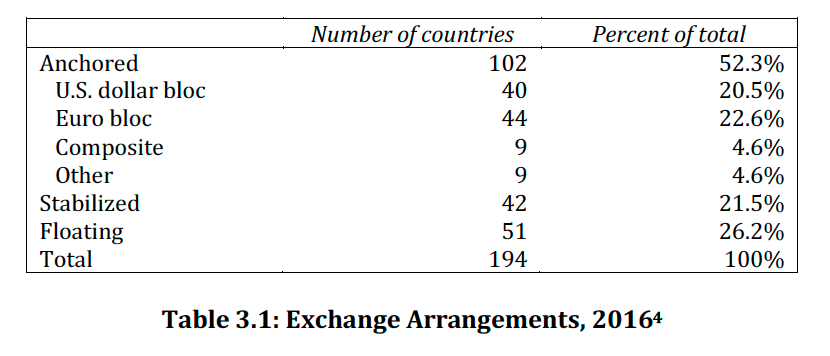

This is easy for the United States, or the Eurozone, because most of the countries in the world already link their currencies to the USD or EUR. If you also include those that have a “soft peg” or “crawling peg,” (called “stabilized” currencies) the percentage rises to about 75%. It would be harder for China or some smaller country, where there is not a pre-existing currency bloc. But, most of the world is already arranged in “currency blocs.” The idea that all currencies are floating currencies today is not in the least bit true.

This is from The Magic Formula, based on IMF categorizations:

Also, the USD and EUR blocs, plus other major currencies like the GBP or JPY, and better-managed floating currencies like the KRW, MYR or CAD, tend to be pretty tightly tied to each other. They all actively avoid large exchange rate swings. So, in practice, there is already a loose “global unified currency bloc,” which basically arises from the desire to avoid destabilizing exchange rate swings.