We now come to Chapter 7 of The Gold Standard, Retrospect and Prospect, which is a paper by Bryan Cutsinger called, “Is the Gold Standard Feasible?”

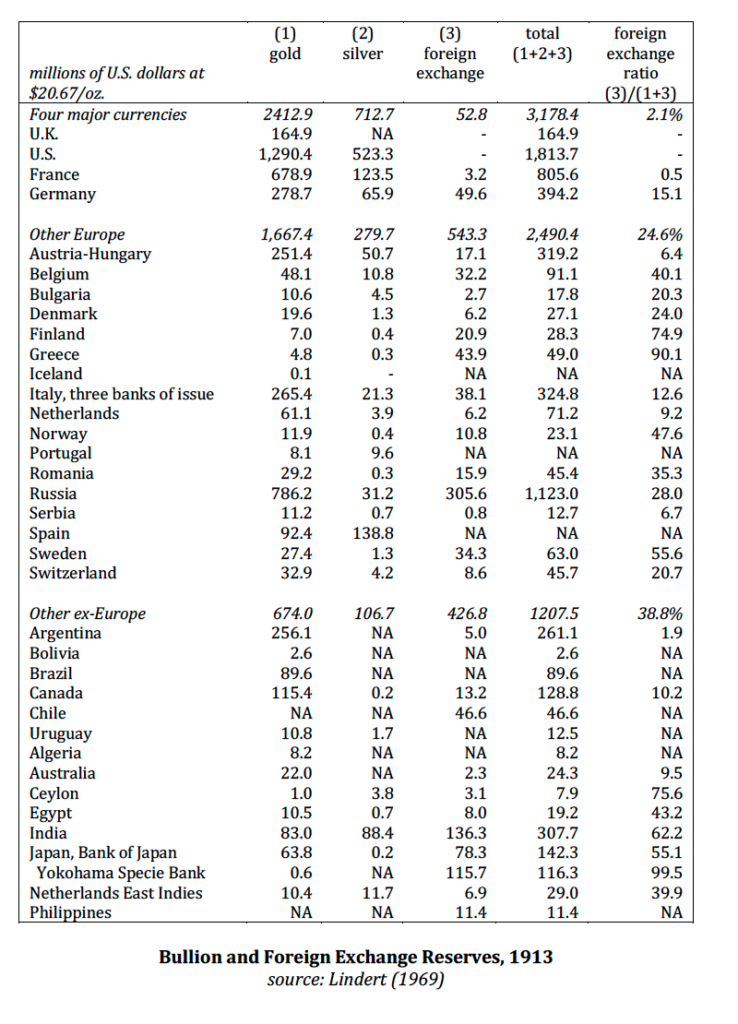

Since a “gold standard” means only that the currency’s value will be fixed to gold, this question amounts to: “Can we keep a currency stable vs. gold?” The answer, obviously, is yes. It is not that hard to stabilize a currency’s value, reliably. Currency boards do this today, and as I pointed out earlier, currency boards often do not actually hold any of the target currency as a reserve asset. For example, a euro currency board does not actually hold any euros, in the form of euro banknotes or deposits at the ECB. They hold only euro-denominated debt, and perhaps bank deposits. Before the issuance of euro banknotes in 2002, for a few years 1999-2001, the Eurozone central banks linked their currencies to a “euro” that was basically imaginary — and did this successfully. This would be comparable to a gold standard system that does not actually have any gold bullion. The common way to accomplish this in the past was to hold the debt denominated in a foreign gold-linked currency, or a “gold exchange standard.” As I pointed out in Gold: The Final Standard, this was already common practice by 1910. Only three major central banks — Britain, the US (distributed system) and France did not hold foreign reserves.

The author remarks that “the type of gold standard I consider is similar to the classical gold standard that operated from 1879 to 1914,” and then does nothing of the sort. His proposals do seem to resemble the US’s National Bank system, which was something of an outlier already by that time, compared to Europe which was mostly already using central banks (near-monopoly currency issuers), although often with some smaller secondary currency issuers. Since he uses 1879 as the start date (the year that the US returned to gold after a floating dollar after the Civil War), presumably this is what he means, but this is not made clear.

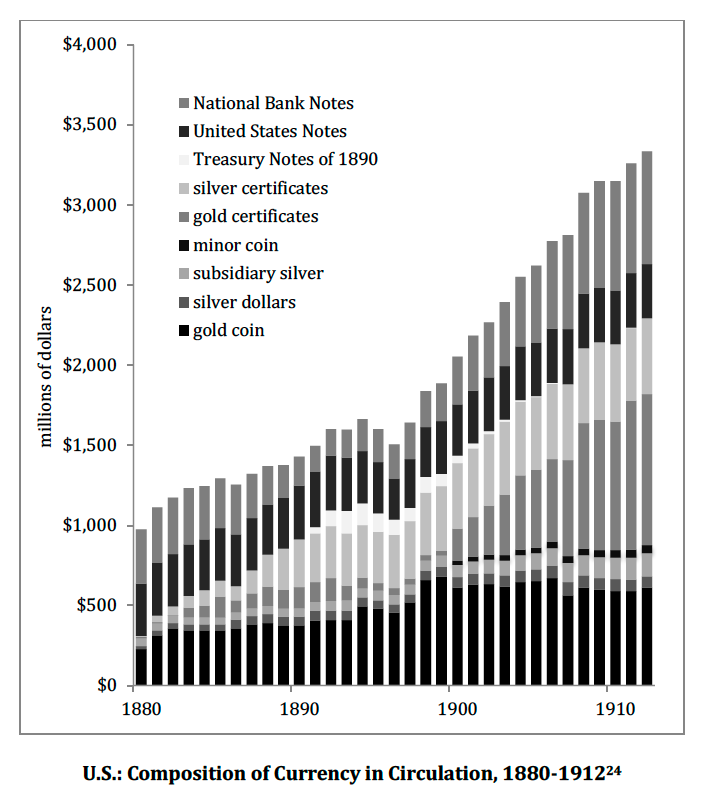

The National Bank System was made up of banks that both operated as commercial lending banks, and as currency issuers, using the same balance sheet. Nobody suggests this model today. Even where distributed issuers (“free banking”) is proposed, these issuers are solely currency issuers, like a cryptocurrency stablecoin, segregated from regular lending. Also, the National Bank System offered redeemability for these National Bank banknotes not in gold coins, but in Treasury Gold Certificates, a paper currency issued by the Treasury for that purpose. These Treasury Gold Certificates were supposed to have, I believe, 100% bullion reserve backing, but I wonder if that was actually true. Not surprisingly, the Treasury Gold Certificates became the most common banknote of the 1879-1913 era in the US, with United States Notes (“greenbacks” from the Civil War) and Treasury Silver Certificates also effectively linked to gold.

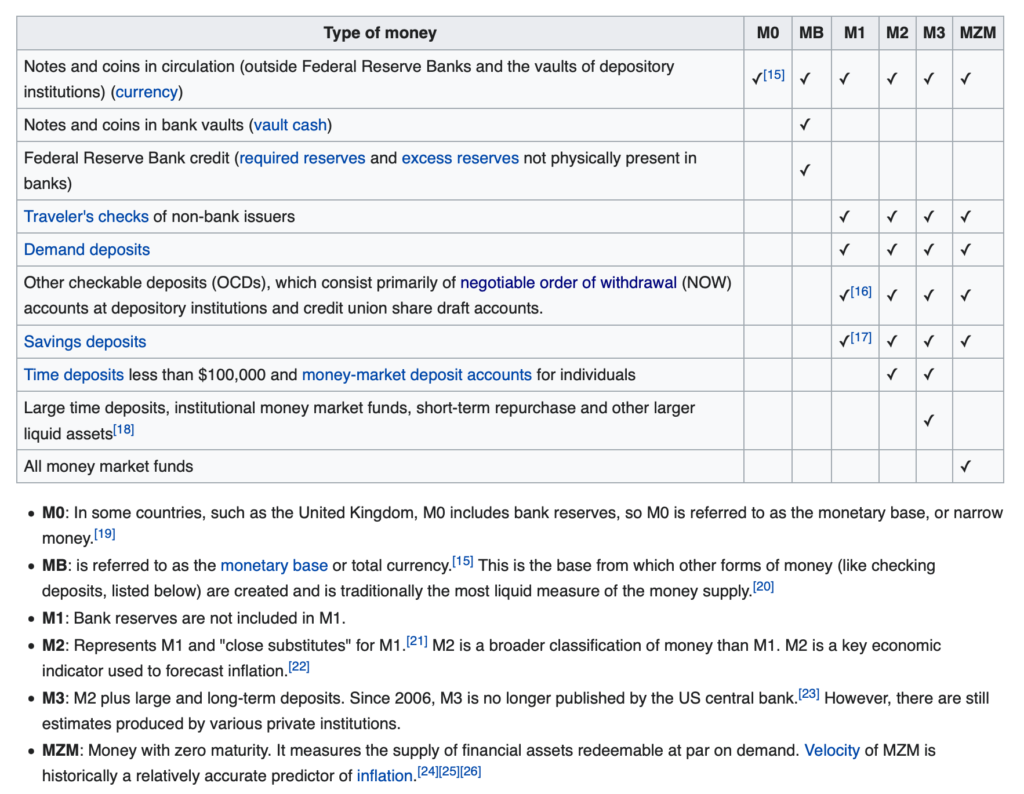

From this, the author proposes that the measure of “reserve ratio” of gold should be: M2 or M3. Here’s Wikipedia:

Now, as you can see, M2 and M3 not only include demand deposits at banks, but also time deposits. Whaaaat? Why would anyone consider a bank time deposit, one of the most illiquid debt instruments around since you can’t even sell it on the secondary market like a bond, as “money”? Considering bank demand deposits (M1, not M2) as potentially subject to redemption does make sense, when we consider that the banks of the National Bank System had both currency liabilities (banknotes) and deposit liabilities on the same balance sheet. That is, unlike commercial banks today, which would be subject to redemption of deposits in “dollars” (Federal Reserve base money), with the base money at the Federal Reserve alone then subject to gold conversion, note-issuing commercial banks of the National Bank era might be obligated to convert deposits to gold. But, as I mentioned, I believe the system actually allowed conversion to Treasury Gold Certificates, which is not the same thing, but is quite a bit like the present system where bank liabilities are “convertible” or “redeemable” in Federal Reserve (instead of Treasury) base money. So, this proposed model actually better describes the typical operations of note-issuing banks from before 1860 in the US, when the Treasury was generally out of the banknote business, and bank liabilities were typically convertible to coinage.

The main point is, this is not a very good description even of the National Bank era of 1879-1913, not a description of all the other countries in the world during the Classical Gold Standard period (1870-1913), and not a description of any system that anyone proposes today, not even those who promote a “free banking” alternative. Just to give an idea, M3 today for the US is $21.6 trillion, while Base Money, which is the only actual “money” today and the only thing that would be subject to gold conversion, is $6 trillion.

The author then relates this figure, M2/M3, arrived at from vague similarities to the National Bank era, with today’s central banks (not the same), and also, the present gold holdings of those central banks. If, today, the Federal Reserve offered gold conversion on “dollars,” the only “dollars” that would be subject to conversion are the actual liabilities of the Federal Reserve, banknotes and deposits, or Base Money. If, today, we adopted a “free banking” model, then the present gold holdings of central banks would be irrelevant, since we are basically putting the central banks out of business.

Then we have a section on the “costs of maintaining a gold standard.” There is a vague implication that national governments would have to pay this “cost,” from their regular fiscal account. Money creation is a profitable business. It doesn’t cost money, it makes a profit. You could argue that there would be less of a profit, if there were higher holdings of gold as a reserve asset. But, central banks already hold gold, so things would not necessarily be much different than they are today — this is a premise of the paper. Central banks (or other currency issuers) acquire this gold by trading either new base money units (such as banknotes) for it, or for swapping existing reserve assets, such as government bonds. So, there is no cost to the government.

June 30, 2016: The Nonexistent “Social Costs” of a Gold Standard System

As for the broader costs, of mining gold, this did not stop even for a moment when the whole world went off gold in 1971. GFMS estimated that there were 205,237 metric tons of aboveground gold in the world in 2021, and 88,688 tons in 1970. In other words, 57% of all the gold that has ever been mined, has been mined since 1970. It has nothing to do with whether currencies are or are not linked to gold. The figure for 1910 was 33,676. So, there is about 6 times more gold in the world today than in 1910.

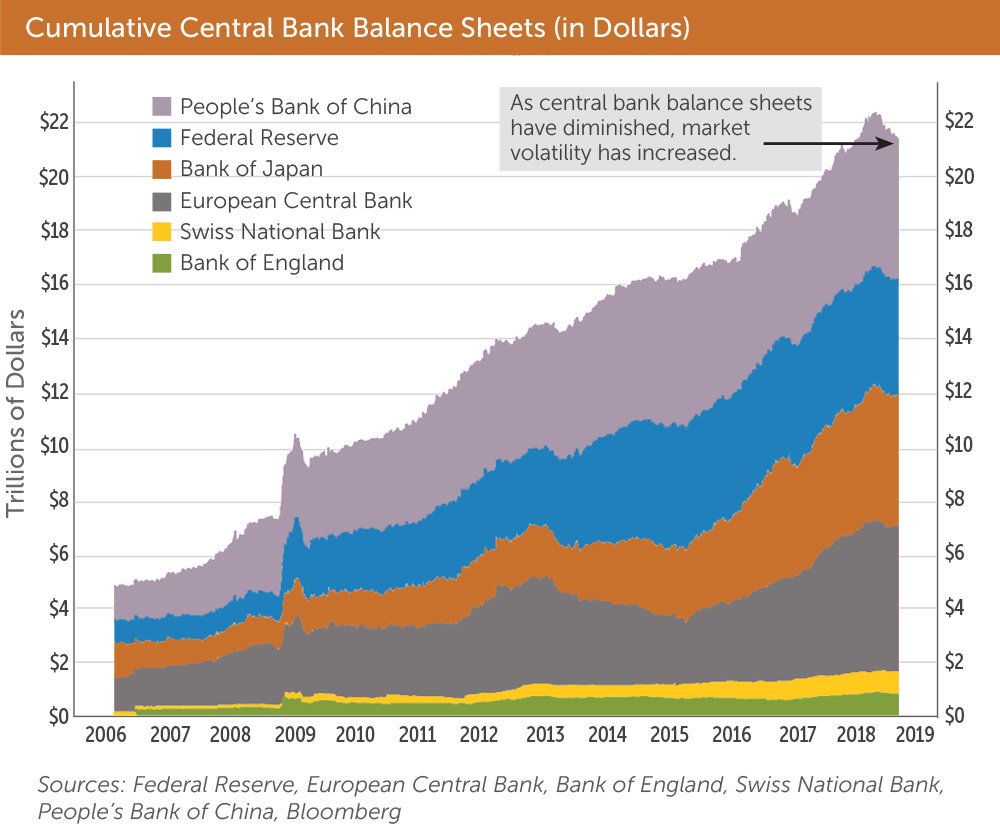

Today, the top 100 central banks have total balance sheet assets of $42 trillion. Total Assets used to be close to Base Money, but today it is not. For example, the Federal Reserve had Total Assets of about $9 trillion, and $6 trillion of base money. Total central bank gold holdings were 35,568 metric tons, or about 1.157 billion ounces, worth $2.083 trillion. So, the present potential gold reserve ratio of central banks looks to be about 5%, or a little higher since base money is less than total assets. But, since we are comparing to the 1870-1913 “Classical gold standard” period, we find that most central banks in the world at that time held foreign currency reserves, or varying degrees of a “gold exchange standard.” This was also the case in the 1920s and again in Bretton Woods.

We would probably expect most central banks to “economize on gold” by using foreign exchange reserves in gold-linked currencies, in any future system, just as was the case in 1910, 1925, and 1944. Or, if you don’t like that system, you can make a new one, with many potential options. In the end, it just has to work: it has to keep the value of the currency reliably linked to gold.

If we take just the major central banks, it looks like this:

They have total assets of about $21 trillion, with base money again a figure somewhat below this. Against this, they have 23,049 tons of gold, about 741 million ounces, worth about $1,334 billion. This works out to a reserve ratio somewhat above 6%.

Monetary Rules: Is a Constrained Central Bank As Good As Gold?

Let’s move on to Chapter 8, “Monetary Rules: Is a Constrained Central Bank As Good As Gold?” by Alexander Salter

To the question in the title we have to ask again: “as good at what?” Since the purpose of a gold standard system is to approach the Classical ideal of a currency perfectly stable in value, we ask whether any of these proposals offers the promise (since none of them have been actually tried) of producing a currency more stable in value than gold.

The answer is obviously NO, because none of these proposals have that as a goal, and in fact, their other stated goals are completely contradictory to Stable Value. The outcome of any of these proposals would be a currency whose value varies somewhat unpredictably, as the outcome of a project of macroeconomic manipulation similar to what central banks are doing today, although somewhat more systematized.

Well, that was easy.

Salter begins with some rather dumb misrepresentations of the gold standard, citing the earlier paper in the book (Chapter 3) while completely misunderstanding the point of that earlier paper.

A well-functioning gold standard has many desirable properties. Perhaps the most desirable is its automatically-adjusting supply. As Peter C. Earle and William J. Luther explain in Chapter 3, the supply of money on a gold standard expands and contracts as needed to stabilize the purchasing power of money over the long run. Moreover, it does so without requiring anyone to consciously act in the interest of society. Knowing that they will bear the costs or reap the benefits of their actions, miners bring as much or as little gold to the market as is required. The result is a self-adjusting supply mechanism that anchors long-run expectations and reduces the cost of long-run contracting.

A gold standard is far from perfect, however. For starters, its automatically-adjusting supply mechanism is somewhat sluggish. Consider an unexpected increase in the demand to hold gold coins. While miners will increase production and eventually bring sufficient gold to market to accommodate the increase in demand, they will not accomplish this overnight. In the meantime, the purchasing power of gold rises and, correspondingly, the price level falls. Businesses will tend to scale back production, as consumers abstain from their usual purchases, reducing real output and employment until expectations adjust. This temporary slump is not due to changes in our ability to produce valuable goods and services, however. It is, instead, an unfortunate byproduct of the sluggish money supply mechanism.

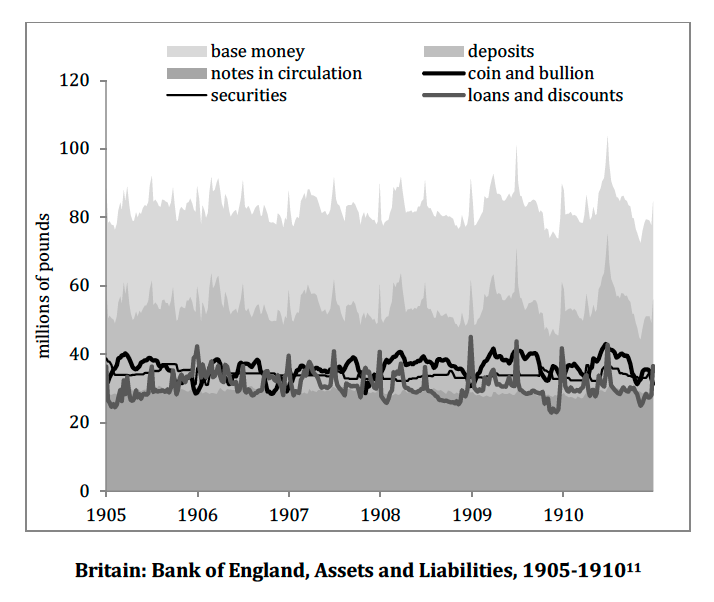

The prior paper (Chapter 3) argued that gold maintained a stable value because, if the value of gold rose, mining production would become more profitable and leading to more mine production. The converse would occur if the value of gold fell. This has little to do with the “money supply” of gold coins, since, as the authors in Chapter 3 noted, there is considerable gold held in nonmonetary form, which could be transferred to the monetary (coinage) category, or vice versa depending on the conditions. Also, foreign coins were often used, so, in a pinch, you could get some foreign coins. Of course all of this only applies to a 100% coinage system, which hasn’t been around since the mid-17th century and the widespread adoption of paper banknotes. The base money supply under a gold standard system can adjust as quickly you like, to the conditions of the day. Walter Bagehot wrote a book about how the Bank of England did just that: Lombard Street (1873), which you can read here. If we look at the Bank of England balance sheet, we find that there was a lot of short-term activity, although it was somewhat stable in the longer term. Nothing “sluggish” about it, and nothing related to mining production.

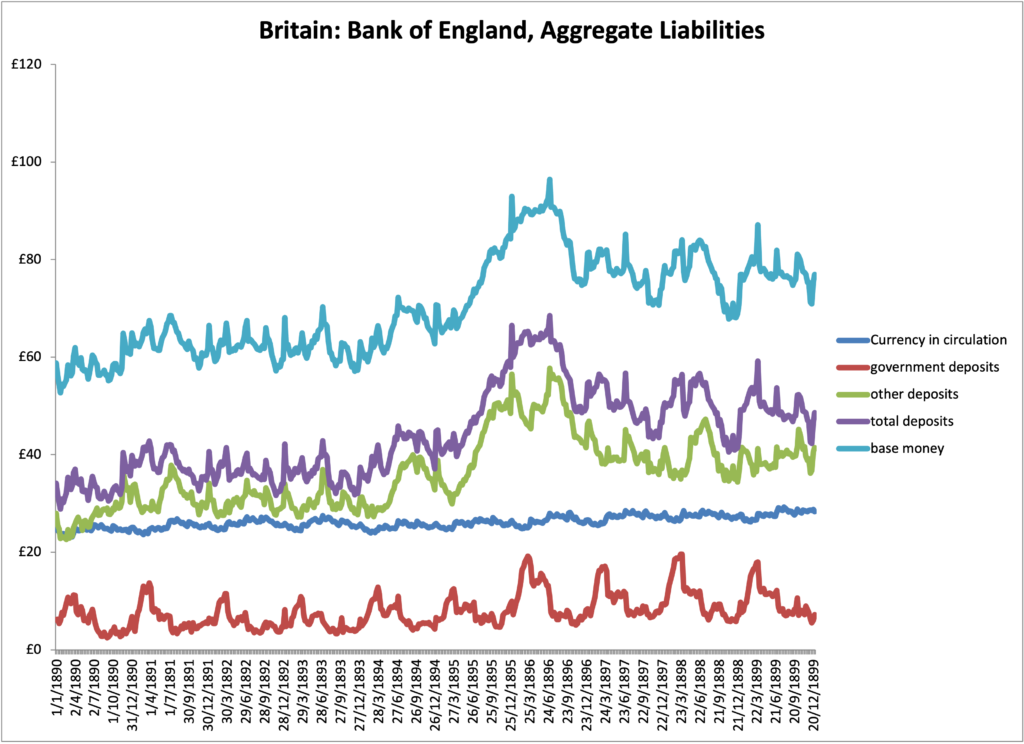

For an example with a little more action, here is the BOE during the 1890s. In particular, there is some turmoil around 1896, which I think was related to the “free coinage of silver” debates in the US. If you wanted to flee USD assets for safety, where would you go? The British pound, of course.

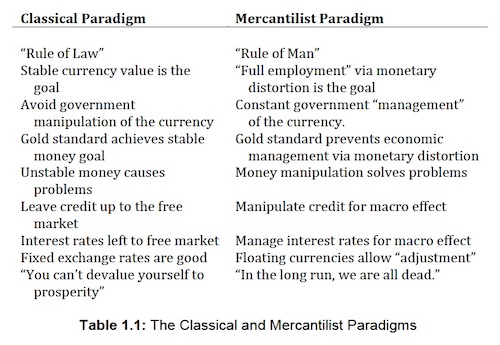

Instead of maintaining Stable Value, the Classical Ideal, the author basically adopts the “Fed dual mandate” model, which is a justification for floating fiat currencies and macroeconomic manipulation via currency and interest rate distortion. It is a Mercantilist or Soft Money ideal.

This leads to proposals for CPI or price-level targeting, Nominal GDP targeting, and the Taylor Rule. I’ve talked about some of these in the past.

Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting series

May 14, 2020: What Would It Look Like If We Had NGDP Targeting Today?

November 18, 2016: JFK Vs. Nixon = Gold Vs. NGDP Targeting

June 26, 2019: Stable Value Is Our Monetary Goal, Not “Stable Prices”

February 12, 2018: “Rules-Based” Monetary Proposals Won’t Create Stable Money

Rather pointedly, the author fails to mention the one “rules-based” system that everyone used in the past, and which most countries still use today: fixing the value of the currency to some external standard, ideally using “automatic” mechanisms resembling a currency board today. In the past, this was gold. Today, it is typically the USD or EUR. (Actually, it was the USD, British pound, French franc and German mark in the past too, but those were also linked to gold.) Unlike all the proposed “rules” in this paper, which have never been tried, this has centuries of experience behind it — centuries when the results were actually rather good.

The author has an interesting section at the end where he concludes that, although you can make up a variety of “monetary rules” while sitting on the potty, it is an open question whether any government institution can actually be relied upon to implement these rules. The author concludes that it is not obvious at all that any central bank could be relied upon to actually implement any of these proposed rules — a problem of governance.

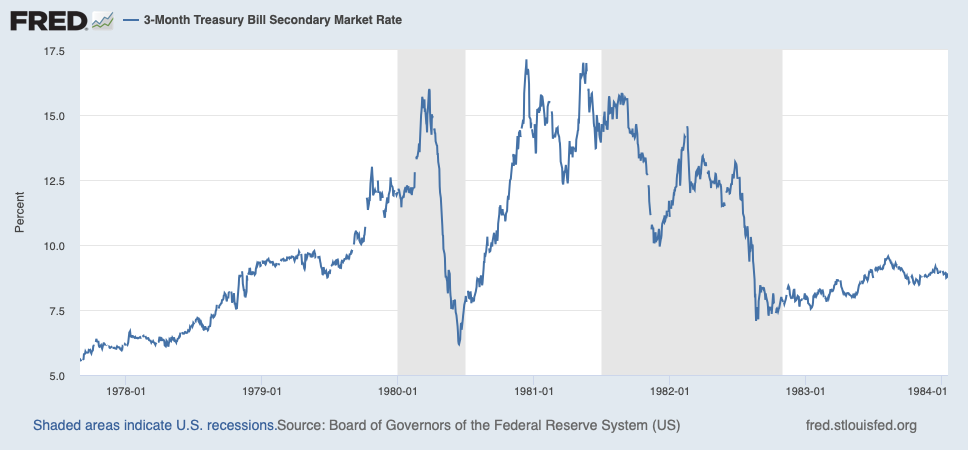

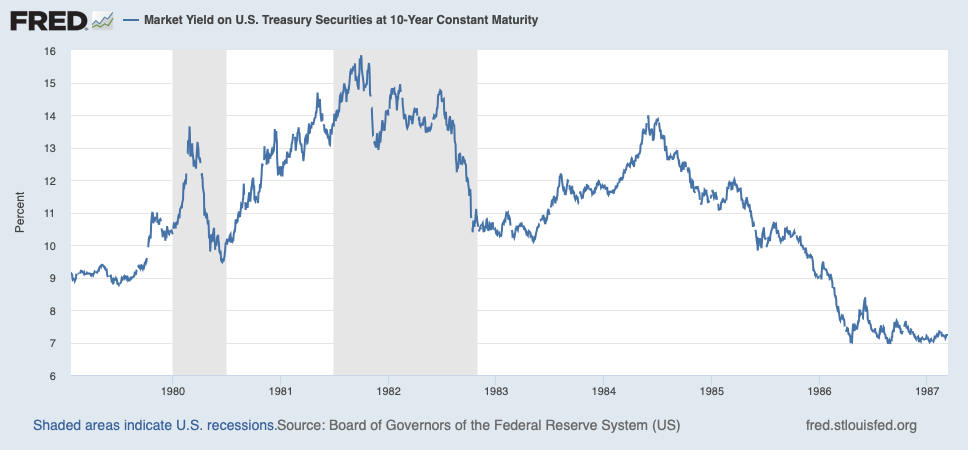

What actually happens in practice is: such a system would soon lead to some unpleasant unintended outcome. Then, the central bank would override the rule to deal with the unexpected problem. This was exactly what happened when the Federal Reserve attempted to impose a Friedman Monetarist framework in 1979 to 1982. This is the typical MV=PY stuff. Note that this equation has no mention of: 1) the value of the currency; and 2) interest rates. Guess what happened? The value of the currency went all over the place, and naturally, debt markets, being unsure of what the future value of the currency would be, and now unconstrained by an interest rate target (which would have come into conflict with the Monetarist framework), had wild swings in interest rates. You could have predicted this beforehand, and people did.

After Volcker adopted Monetarism in August 1979, the value of the dollar collapsed from about $1000=3 oz. to $1000/oz.=1 oz. ($300/oz. to $850/oz.). Then, it soared higher back to $1000=3 oz. in 1982, before Volcker publicly abandoned the project.

Here is the market rate on 3-month Treasury bills:

You can see that it explodes into chaos when Volcker adopted the Monetarist system, and then calmed down when he abandoned it in 1982.

Here are 10yr Treasury yields:

So, you can see that there can be unintended consequences. Today, for example, we have NGDP Targeting, which is third-generation Monetarism. It is the updated version of what Volcker tried in 1979. It had to be updated, because, obviously, second-generation Monetarism didn’t work.

The obvious question for NGDP targeting is: what is the value of the currency? This leads directly into the exchange rate with other currencies, like the euro. If the US adopted NGDP Targeting, what would the exchange rate with the euro, or yen or GBP, look like? Obviously, those are floating fiat currencies too, so it is hard to say. But, central bankers today actively avoid large exchange rate swings. This is part of their “discretionary” seat-of-the-pants process. Since we would be eliminating this “discretionary, seat-of-the-pants” element, then exchange rates could become as wild as the USD value (vs. gold) or interest rates in 1979-1982. Businessmen and investors would howl with anger, and then the central bank would have to abandon its “rules based” system, just as Volcker did, for similar reasons, in 1982.

These are some reasons why the gold standard, or other “fixed value” systems such as a USD currency board, have been superior also from a political standpoint. We have seen that governments can abide by a fixed-value policy for decades on end — even centuries. It is not only technically attractive, it is politically feasible. It is something that human governments and institutions can actually do. It is the only “rules-based system” that ever worked, and actually, it worked very well.