The Reichsbank, 1924-1941

August 3, 2014

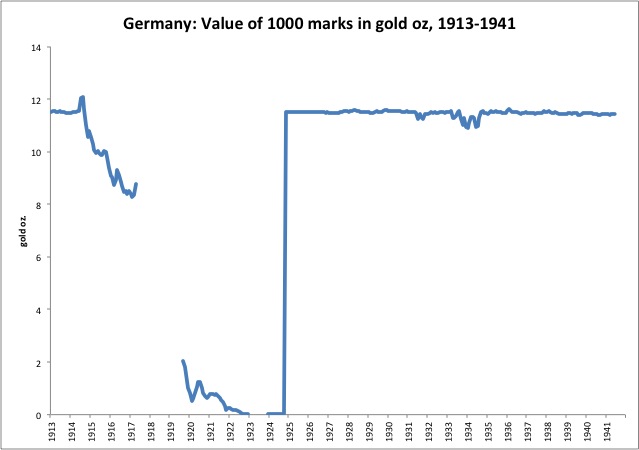

Here’s something you don’t see everyday: a look at Germany’s Reichsbank during the 1920s and 1930s. The German mark was nominally stable vs. gold throughout the interwar period, but that was achieved with heavy capital controls especially after 1931 I think.

This continues our look at some major central banks during the 1914-1941 period.

July 27, 2014: The Bank of France, 1914-1941

July 20, 2014: The Bank of England, 1914-1941

January 26, 2014: The Federal Reserve in the 1930s #2: Interest Rates

January 19, 2014: The Federal Reserve in the 1930s

July 18, 2014: Foreign Exchange Rates 1913-1941 #8: A Brief Summary

December 23, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 4: The Historical Record

December 16, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 3: Balance Sheet and Base Money

November 25, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s 2: Interest Rates

November 18, 2012: The Federal Reserve in the 1920s

The source of our data is the Federal Reserve Banking and Monetary Statistics, 1914-1941.

http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/publication/?pid=38

After the famous hyperinflation in the early 1920s, Germany maintained the mark’s link to gold until WWII, at least in a nominal or official basis. The 1923 gold parity was the same as the pre-WWI parity, although it didn’t have to be. Just tradition.

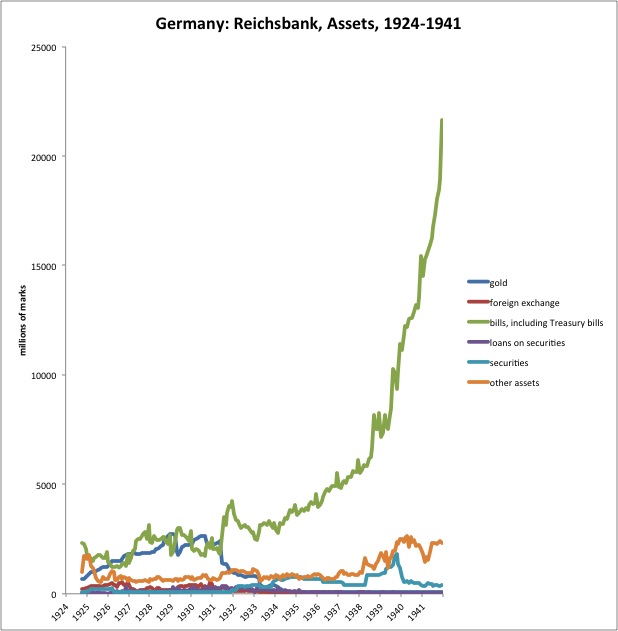

We see here a big drop in gold bullion holdings after 1931, and of course a giant rise later in government Treasury bills. It looks like there was some printing-press finance for the war beginning around 1938 or so.

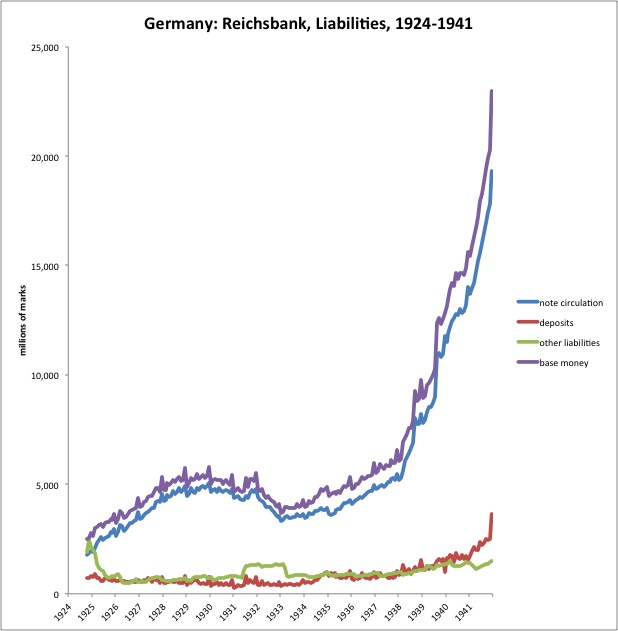

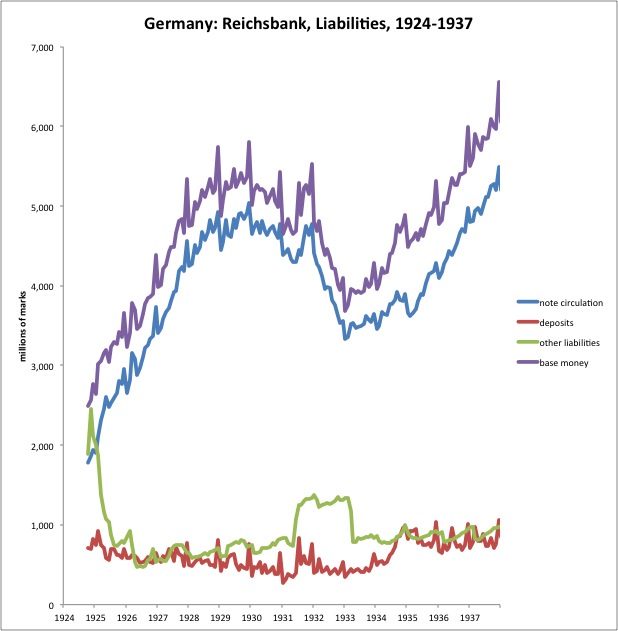

Liabilities consisted mostly of banknotes, with a little bit of deposits (bank reserves).

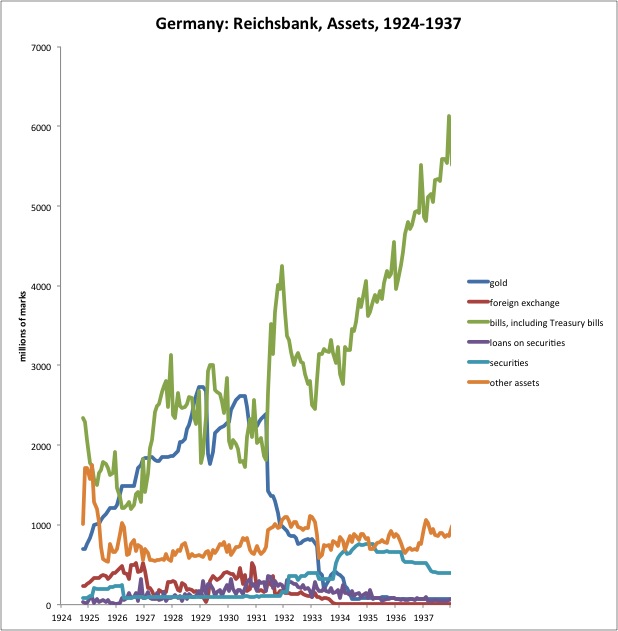

Let’s look at just the period to 1937, skipping for now the big rise toward the end of the 1930s.

Again, we see that big drop in gold holdings. However, the fact that it continues until 1934 indicates that it was still possible to somehow acquire gold; or, perhaps the government itself was using it to obtain foreign imports.

Base money makes a big contraction beginning in 1931. There was a lot going on around that time, including some bankruptcies of big banks and also major sovereign defaults. Germany had a major sovereign default in 1932; I think Austria was in 1931. I would not consider this reduction in base money supply “contractionary” unless the value of the mark rose; but there was hardly any reason for that, and the mark was actually stable in value. So, it was a reduction in supply in reaction to a reduction in demand, and there certainly were a lot of reasons that people would perhaps not really want to hold marks. This reduction in supply, in the context of maintaining a gold parity value, doesn’t really have many broader effects, although short-term interest rates can be affected for a short while.

What if, for example, the Bank of France asked for its mark-denominated assets (if indeed it had any; most foreign holdings were British pound and U.S. dollar assets I think) to be redeemed in gold bullion at the Reichsbank? Actually, a government bond is not redeemable for gold under a gold standard system; only the liabilities of the currency manager (Reichsbank), which are basically banknotes and domestic commercial bank deposits at the Reichsbank, or base money. But, let’s say that the Bank of France sold the German government bonds for cash (actually a bank deposit at a commercial bank, which is a form of debt liability of the commercial bank), and then asked the commercial bank to redeem that for gold. The commercial bank could default, in essence saying that it would not pay back its deposit in the form of base money. However, let’s say that, one way or another, the commercial bank does ask for its base money (bank deposits) at the Reichsbank to be redeemed in gold. The Reichsbank could, conceivably, refuse to do so, arguing (plausibly) that it would be overly disruptive given the very large size of the order, or perhaps demand that it be spread out over some time period. The Bank of France is not without options here; they can just sell their bonds for cash, and then use the cash to buy gold bullion on the open market (from miners for example, or anyone wishing to sell gold bullion), thus accomplishing the same thing as if they had acquired gold bullion directly from the Reichsbank. They could even engage in forward contracts with the miners, in essence buying future production. The main reason they might not do this is if the market price of gold in marks was higher than the parity value; let’s say, 55 marks/ounce instead of parity at 50. In that case, the mark is weak compared to its gold parity, or that marks are oversupplied, and thus that a reduction in base money supply (resulting from gold redemption) is exactly what was needed to return the mark to its gold parity value.

But, let’s say that the Reichsbank does indeed deliver gold to the commercial bank, and the commercial bank does indeed deliver gold to the Bank of France, and that the German base money supply does indeed contract by the amount of the gold redemption, at least in the first instance. Actually, that did NOT happen, as the increase in Treasury bills effectively offset the initial outflow of gold. But, in this scenario, one of two things might happen: the value of the mark might not rise, in which case the gold redemption represented a genuine net reduction in demand, and the reduction in base money supply was exactly correct to accommodate this decrease in demand. Or, the value of the mark might rise, in which case arbitrageurs would step in. Let’s say the mark/gold parity was 50 marks/ounce, and the market value of the mark was 45 marks/ounce. Arbitrageurs would come in and buy gold with marks at 45 marks/ounce in the open market, and then give the gold to the Reichsbank and receive 50 marks in return. The Reichsbank’s assets would thus expand by one ounce of gold bullion and base money would expand by 50 marks. Arbitrageurs would make 5 marks of risk-free profit. This would continue until there was no more profit to be made; in other words, the market value of the mark was at the gold parity of 50 marks/ounce. Or, the value of the mark might rise against some other currency (the US dollar) by some little margin, in which case the Reichsbank could step in and buy Treasury bills in the open market to expand the base money supply, and reduce the value of the mark until it returned to its official gold parity (and implied foreign exchange rate). Or, the Reichsbank could buy dollars and sell marks, and the asset side of the balance sheet would ultimately reflect an increase not in German government bills, but U.S. government bills, which would be recorded as an increase in “foreign exchange.” Another potential process is that, as the commercial bank requires more base money to meet deposit redemptions into gold bullion, it must effectively borrow these bank reserves (note the rather low amount of bank reserves throughout this time period). This could cause an increase in short-term interest rates; and in any case, the bank can then discount bills at the Reichsbank, thus increasing the Reichsbank’s bill holdings. Under the principles of “19th century central banking,” these bank loans could be “short-term, self-cancelling loans,” allowed to roll off as the bills mature. Thus, base money naturally contracts again, but spread out over a longer time period. The ultimate result is that the effects of a sudden gold redemption are spread out. If the effect of the rolloff of bills is that base money is insufficient, then gold inflows increase to offset the bill rolloff. Or, if the contraction of base money is warranted over a longer time period, the bills roll off but the value of the mark does not rise sufficiently to cause bullion inflows. You can see that there are a lot of mechanisms in place that would self-adjust to keep the supply of base money exactly what it should be to maintain the gold parity, no matter what the Bank of France or others might do.

Actually, the proximate cause of the decline in base money beginning in 1931 was not the decrease in gold bullion, as that was immediately offset by an increase in holdings of Treasury bills. Rather, it was the decline in holdings of Treasury bills thereafter. Why should Treasury bills decline? Since these can only increase or decrease via open-market operations (assuming automatic rollovers of maturing bills), changes are thus due to the decisions of the Reichsbank itself, not the Bank of France or anyone else. Probably, they were reacting to weakness of the mark in the forex market and also compared to the gold parity, shrinking the monetary base in response exactly as is required to maintain the gold parity value for the mark. In other words, the contraction in base money 1931-1933 most probably represent adjustments necessary to maintain the mark at its parity value in response to declining demand for marks.

If this is confusing, then please see my book Gold: the Monetary Polaris, where these scenarios are described in detail. Indeed, the decline in base money from about 5 billion marks to about 4 billion marks is exactly the kind of “20% reduction in base money supply” that I mention is usually about right to react to a currency crisis. What a coincidence. Not really–it’s just that I’ve seen this before, and make the example of Russia in 2009 in my book. A similar reduction in base money supply (probably less than 20% in those cases) would have allowed Britain to avoid devaluation in 1931, or the U.S. in 1971.

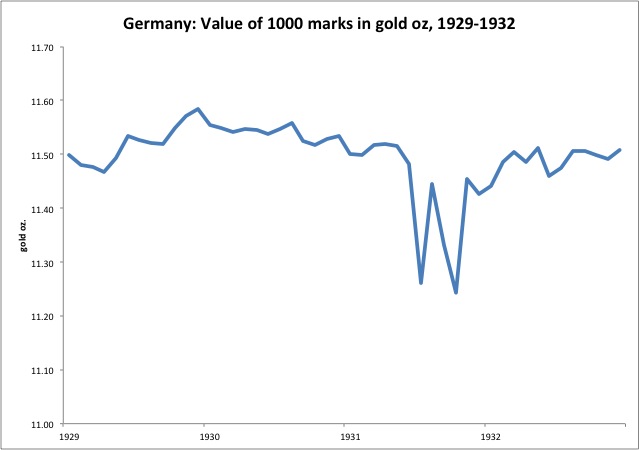

We can see from the value of the mark vs. gold at the top (actually the value of the mark vs. the dollar, translated into gold), that the mark indeed had a sag in 1931 below its parity value, and that this sag was indeed corrected. The “sag” in 1933 might just be a factor of translating the then-declining value of the dollar vs. gold into a mark/gold value, a complicated way of saying it is perhaps statistical noise that should be ignored.

In any case, unlike the central banks of the U.S., Britain and France, where base money was largely unchanged through the 1929-1935 period, the Reichsbank’s base money supply had some ups and downs.

This was quite an eventful time, and a review of historical works would be necessary to get an idea of all the things that were going on then. Simultaneous bank and sovereign default has a way of making a mess of everything.