The Triad of City Design Failure

November 24, 2013

One thing you start thinking about, when you understand what I am talking about regarding the Traditional City, is: why don’t people get it?

Click Here for the Traditional City/Heroic Materialism Archive

This has two aspects. First, people read what I and others have written, and simply don’t understand what we are talking about, and more-or-less don’t like it.

Second, people haven’t figured this out already, despite many thousands of years of human experience with Traditional Cities, and also many thousands of contemporary examples where hundreds of millions of people are already living, in giant modern metropolises or antique country villages.

I think this is, at least in part, because people go round and round what we will call today the Triad of City Design Failure. The triad is:

The 19th Century Hypertrophic City (today called “New Urbanism”)

The 20th Century Hypertrophic City

Suburban Hell

For example, someone thinks that the 19th Century Hypertrophic City is the answer to their problems (“New Urbanist”). Others say “no, no, no, we tried that and it didn’t work.” They then propose what amounts to a 20th Century Hypertrophic City solution (Le Corbusier “tower in a park”). The others then say “no, no, no, we tried that too and it didn’t work.” This leads people to propose what amounts to a Suburban Hell solution (most people in the U.S.). Everyone then says “no, no, no, we definitely tried that and it also didn’t work!”

Each of these is an attempt to fix the problems of the other. Each introduces catastrophic new problems.

It goes around and around like this, for decade after decade, generation after generation, particularly in the United States. Everybody is exhausted, and defaults to whatever seems most expedient, because “nothing can be done.”

Although I am recycling ideas I’ve presented in the past, it seems to me that most people can’t appreciate that all three of these options are failures — proven failures after decades and indeed centuries during which there has been not one example of what I would call success. Most people, it seems, can sense the failure of only one model at a time, and then they place their hopes on one of the other models. It doesn’t work. It demonstrably hasn’t worked for the last two hundred years of trying, in all countries worldwide. That is why I say the Traditional City form, in its contemporary variants which can (but don’t have to) include motorized vehicles, high-rise buildings and most certainly trains and subways, is the only way out of this maze.

The 19th Century Hypertrophic City is the form of virtually all city design in the U.S. before 1920. People in the U.S. think this is “traditional,” because it was common throughout the world in the 19th century (actually beginning around 1780), and there is virtually nothing from before 1780 that still exists in the United States. However, it is very different than the Traditional City design that is common throughout the world, in all cultures, from prehistory to about 1780. The 19th Century Hypertrophic City typically has very wide streets, on the order of 60-100 feet from building-to-building, most commonly in some kind of grid layout. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with wide streets — where they are useful — and indeed Traditional Cities have had them going back to Ancient Rome and before. But, typically 20% or less of total street length in a Traditional City is wider than 25 feet or so. These are what I call Arterial Streets or Grand Boulevards. The other 80%+ of streets are Really Narrow Streets of typically 8-20 feet wide. In the 19th Century Hypertrophic City, all streets become Arterial size or larger. This is true of tiny villages of population <1000, and of course giant cities like New York City.

Some people think this is due to the introduction of automobiles, but actually this transition to very wide streets occurred about 140 years before the widespread use of automobiles, around 1780.

The problems of the 19th Century Hypertrophic City are:

1) The streets are very difficult to pave without the use of asphalt, so they were typically unpaved, and turned into horrible mudpits for much of the year. This then led to the introduction of sidewalks, because it is easy to pave a 3 foot wide sidewalk to people don’t have to walk in the mud. This is very different than the typical Traditional City layout of streets that don’t have a segregated “sidewalk,” but have one flat plane which is used by both pedestrians and wheeled vehicles (remember this is a century before automobiles). The introduction of sidewalks thus implied a large central area which was, by default, dedicated to wheeled vehicles, since it was muddy. This large central lane, which at first wasn’t actually very useful because wagon traffic was never all that high, and people had been sharing their streets with wagons in Traditional Cities for millenia with no particular problems, beginning in the 1920s became a roaring mess of automobile traffic. This produces a very unpleasant environment for humans.

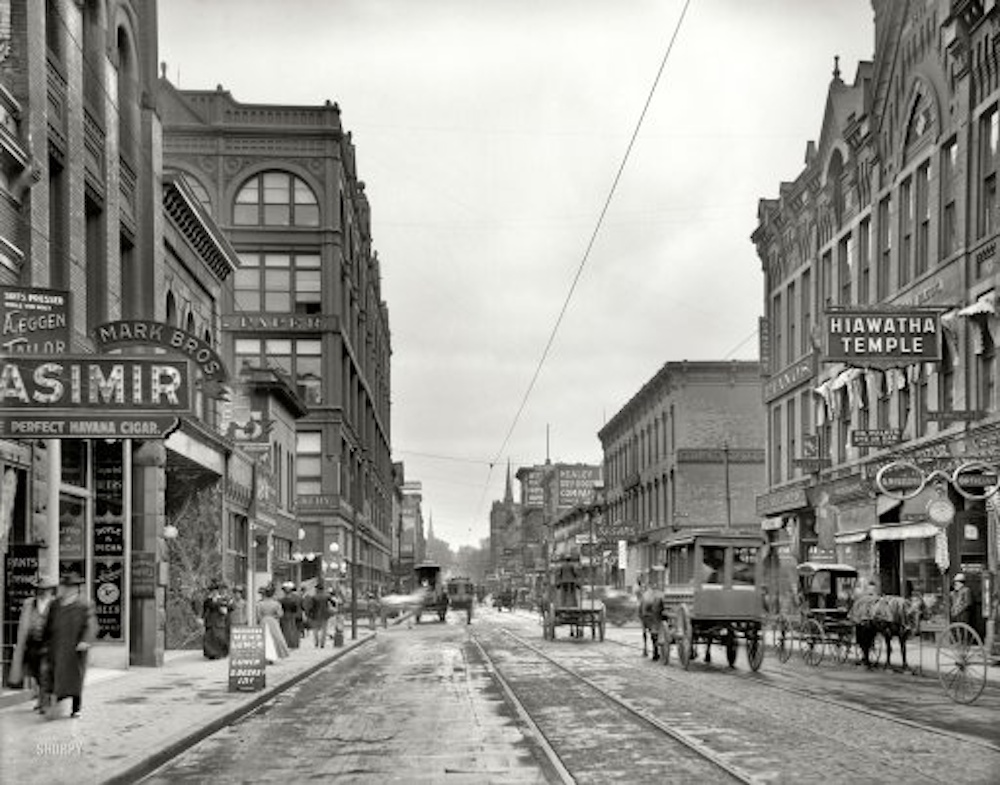

Times Square, Manhattan, New York, New York, USA — New York, NY: Longacre Square, Times Square, 1900, photograph. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

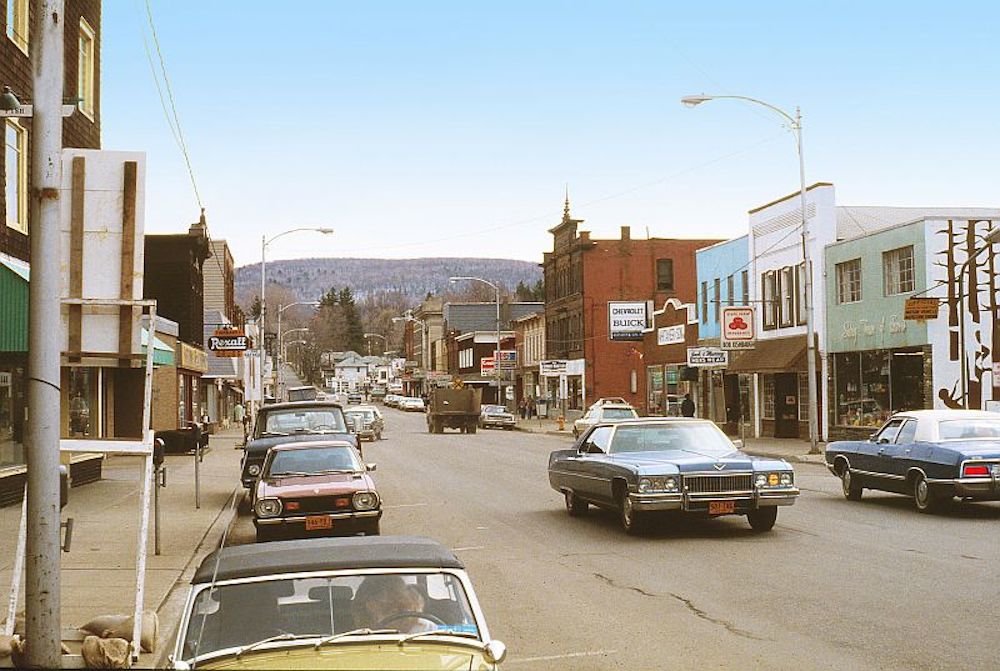

Small Town America. Norwich, NY. This street was laid out in the late 18th century, and the buildings mostly date from the 19th century.

Although Baron von Haussmann was busy making 19th Century Hypertrophic streets in Paris at the time as well, according to the fashion of that time, he was limited to just a few Grand Boulevards. Most of the streets remained Really Narrow in the Traditional City style. In the U.S., which was starting with a blank slate, all the streets could be made Haussmann-sized.

Paris, late 19th Century

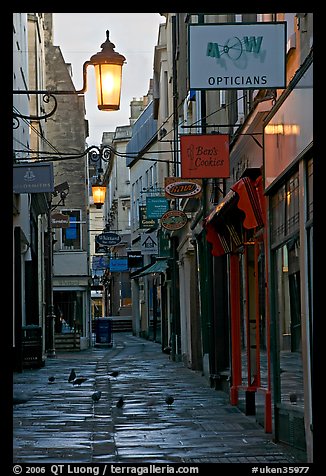

A typical Traditional-City-style Really Narrow Street. Although there is a vestigal “sidewalk”, this is mostly for drainage and property line delineation. If you were walking, you would walk right down the middle of the street (as the motion-blurred people in the distance are indeed doing).

Lamps, pigeons, and narrow street. Bath, Somerset, England, United Kingdom

Somerset, England.

Americans are ethnically descended from British. Why didn’t the Americans make streets like this? This is the Traditional City style, which was supplanted around 1780 by 19th Century Hypertrophism.

Quebec City, Canada. Traditional City style.

Kathmandu, Nepal. What’s the difference between this and Somerset, Quebec City or Paris? Basically, nothing. The Traditional City is the same everywhere.

Note the street width here: about 18 feet. No sidewalks, no central roadway.

2) The very wide streets are horribly wasteful of land. This gets worse as you make blocks smaller, because as the blocks get smaller the streets remain the same (hypertrophic) size, resulting in a larger and larger percentage of land area taken by streets. This naturally led people to make larger blocks, in practice about 200 feet street-to-street instead of about 100 feet typical in Traditional Cities. However, larger blocks lead naturally to larger land plot sizes, which also tend to be very long and skinny. The result is that single-family homes become quite difficult, driving development toward multifamily buildings. This is not particularly problematic in itself, and was common in Traditional Cities for centuries particularly in Europe (not so much in Asia). However, this multifamily development was often not very well thought out. The combination of living in a multifamily building, typically with no yard, courtyard, or park nearby, plus the very wide street filled with automobile traffic directly in front of the building, is a difficult combination especially for families with small children.

3) In the United States, wherever possible, people attempted to live in suburban-style single-family homes surrounded by setbacks on all four sides, on a plot of 1/8th acre (about 5000sf) or greater, with 1/4 acre or greater typically desired. This was true beginning around 1780, and is the typical form of the 19th Century small town or village in the U.S. The combination of very wide streets and suburban-style homes has a maximum population density of about 9,000 people per square mile. This makes all forms of shared transit difficult, because everyone lives a long distance (farther than an easy walk) from any potential train station or even bus stop, and also one’s destination is likely to be too far from a train station or bus stop to walk easily. The result is a reliance upon personal automobiles, which thus requires an even larger land plot due to parking, requires larger streets to accomodate traffic, and requires parking at the destination, all leading to even lower densities and more reliance on personal transportation.

Typical 19th Century house, Norwich, NY. The basic suburban house on a quarter-acre dates from long before automobiles. It has been Americans’ preferred format since the 1780s. This is a very low density format, probably around 2,000 people per square mile in rural villages and small towns.

However, in Europe, villages were normally quite compact, even if also very small. They didn’t spread themselves all over the landscape. Village in France.

Village in France. The density here is at least 30,000 people per square mile (Paris is over 60,000.)

Village in France.

4) Despite the very wide streets (by Traditional City standards), the metropolitan 19th Century Hypertrophic City is also a terrible place to drive. Parking is typically problematic at best, and the grid format of the streets produces many problems. This pushed engineers to make more and larger roads, and to insist on ample parking everywhere, leading to Suburban Hell.

The 19th Century Hypertrophic pattern, in both its small-town or large metropolis format, does not produce comfortable living environments. Virtually everyone finds 19th Century Hypertrophic metropolises, such as central New York City or Chicago, to be quite difficult, ugly and unfriendly, especially for families with small children, or elderly. Beginning with the advent of trains around 1850, this drove people towards the “suburbs,” (yes, even then), where they could live in a “small town” environment, of single-family homes on 1/8-acre or larger plots. The failure to produce pleasing common areas (streets) drove people to attempt to create pleasing private areas (their suburban yard), as a “refuge from the big city.” The problem here is, of course, very long commutes. Also, it tends to be quite expensive, as people have large amounts of land, large houses, and the need for extensive transportation.

The 19th Century Hypertrophic pattern is generally found to be most pleasant in the “small town” format. In a small town (population typically under 10,000), traffic is moderate and the suburban single-family home on a 1/4 acre (or larger) lot is typically not hard to come by, or unduly expensive since rural farmland is typically close at hand. The problem of a small town is, of course, that it is small. It is small because nobody lives there. As soon as people start to live there, it becomes a suburb of a large city, or a small city itself, with all the intensifying problems of 19th Century Hypertrophism, 20th Century Hypertrophism, or Suburban Hell, plus higher property prices. The reason that a small town is small is because there aren’t any good-paying jobs, because, if there were, people would move there. For this reason, people fantasize about “small town America,” but don’t actually live there (most actual small towns in the U.S. have declining population), because there isn’t any work. This leads people to fantasize about “telecommuting,” which is realistic only for a rather small subset of job types.

Most small towns served as commercial infrastructure in agricultural areas, and as agriculture demanded fewer and fewer people, there was less and less need for commercial infrastructure. For example, let’s say a small town is surrounded by 50 square miles of farmland. In the 19th century, perhaps it took 10,000 people to farm this farmland (3.2 acres per person), in the form of 2,500 farming families averaging four people each. Thus, the town would provide services such as schools, stores, churches, restaurants, medical care, theaters and so forth for 2,500 farming families. Today, if the area still has agriculture at all (most agriculture in the Northeast and Midwest migrated to the South for climate reasons when it became easy to transport food long distances, rendering the farmland abandoned), perhaps it takes only 200 farming families to farm the same 50 square miles. Thus, the need for commercial infrastructure is drastically lessened, and conveniences like mail-order reduce even that.

Non-agricultural industries typically find that larger cities are better suited for their needs than small towns. In other words, the good jobs are in large cities. Thus, the typical pattern is that large cities get larger, while small towns get smaller due to shrinking agricultural employment.

Even in its small town format, the 19th Century Hypertrophic pattern tends to be relatively expensive to live in, as it requires the use of personal automobiles. 19th Century Hypertrophic small towns are not at all dense, with densities well below Suburban Hell (perhaps 2,000 people per square mile), and there is typically not very much within walking distance of a residence. This makes shared transportation near-impossible. It is very different than the Traditional City small rural village, which is usually quite dense (perhaps 30,000 people per square mile, which is actually not that high and achieved with single-family detached residences in many Japanese suburbs today), which puts the entirety of the town or village in easy walking distance. A town of 5,000 people at a density of 30,000 people per square mile is, obviously, only 1/6th of a square mile in size! This is a square 2150 feet on a side, or 550 meters. To this can be added a single bus or train station, which allows access to neighboring towns or distant metropolises without need for an automobile. Although people in the U.S., where small towns are typically very low density in the usual 19th Century Hypertrophic pattern, probably think the idea of a “high density village” is a bizarre fantasy contrary to all the natural laws of economics and human nature (“why jam together ‘like sardines’ when you are surrounded by cheap land?”), actually this format is common in the Traditional City villages of rural Europe, and also in Asia.

It is, in fact, the way things were normally done for thousands of years.

Village in Greece. Very dense! Then, there is an immediate transition to farmland.

Same village, closer up.

This sort of thing (Greece).

Many of the problems of 19th Century Hypertrophism (big city version) could have been mitigated through the extensive use of, for example, courtyards, to provide a protected and pleasant outdoor space for families. This is common in Paris, for example. However, in the U.S., formats such as this were prevented somewhat by the typical progress of densification, where plots for single-family homes (either townhouses or freestanding suburban-type homes) were rebuilt for multifamily use. The plot shapes, typically very long and narrow (due to the wide distance between streets as mentioned previously), did not lend themselves easily to courtyard-type architecture. Or, maybe they just didn’t think of it. People can be grossly stupid.

Courtyard in Paris. You don’t see this in New York City much.

Courtyard in China. This is what a “yard” looks like for a city dweller. It’s not a suburban-style green doughnut of mown grass.

Courtyard in Mexico.

The problems of 19th Century Hypertrophism drove people to either 20th Century Hypertrophism or Suburban Hell. We will look at this more next week.