We’re looking into Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder (2019), by Thomas M. Humphrey and Richard Timberlake.

September 17, 2023: Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed #2: Let’s Review

September 24, 2023: Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed #3: Systemic Issues

You can say a lot about what was going on with US banks during the Great Depression, or specifically the downturn of 1929 to the end of 1933 when, with a combination of the RFC and Deposit Insurance, things stabilized. Almost none of this is in the book we are talking about — a little odd, since that is supposed to be its subject — so let’s take a look on our own.

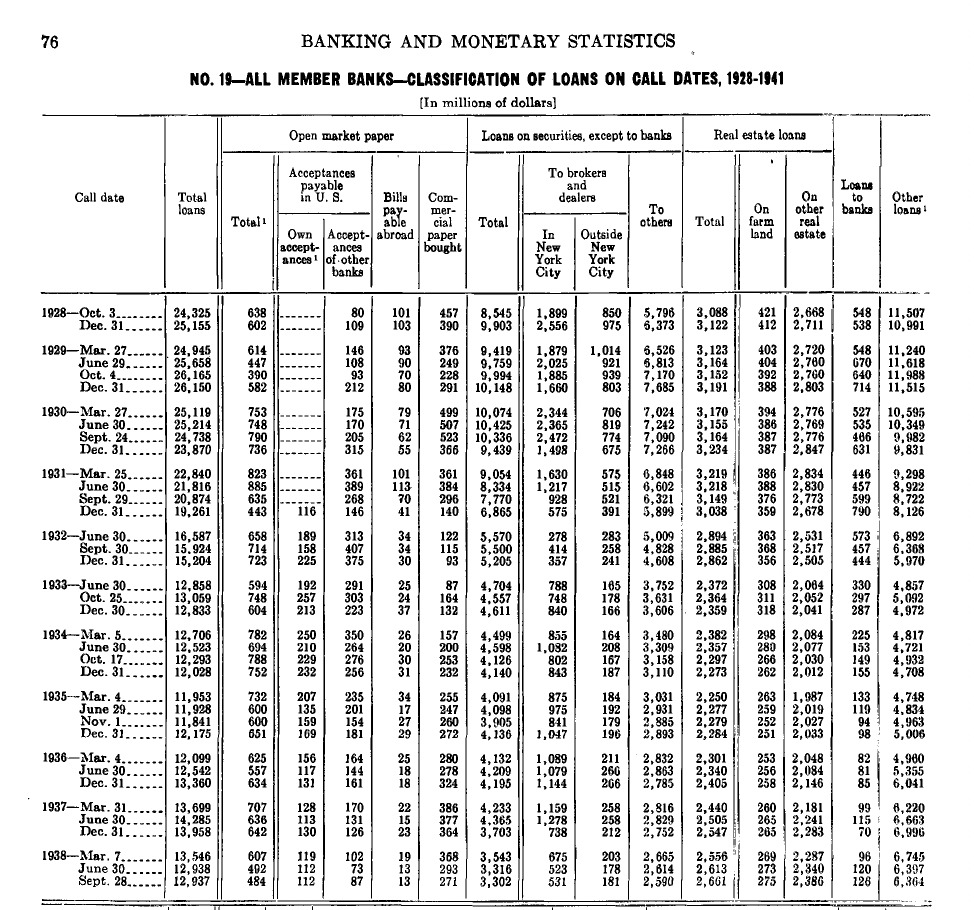

This is from the Federal Reserve Banking and Monetary Statistics, available here:

Federal Reserve Banking and Monetary Statistics, 1914-1941

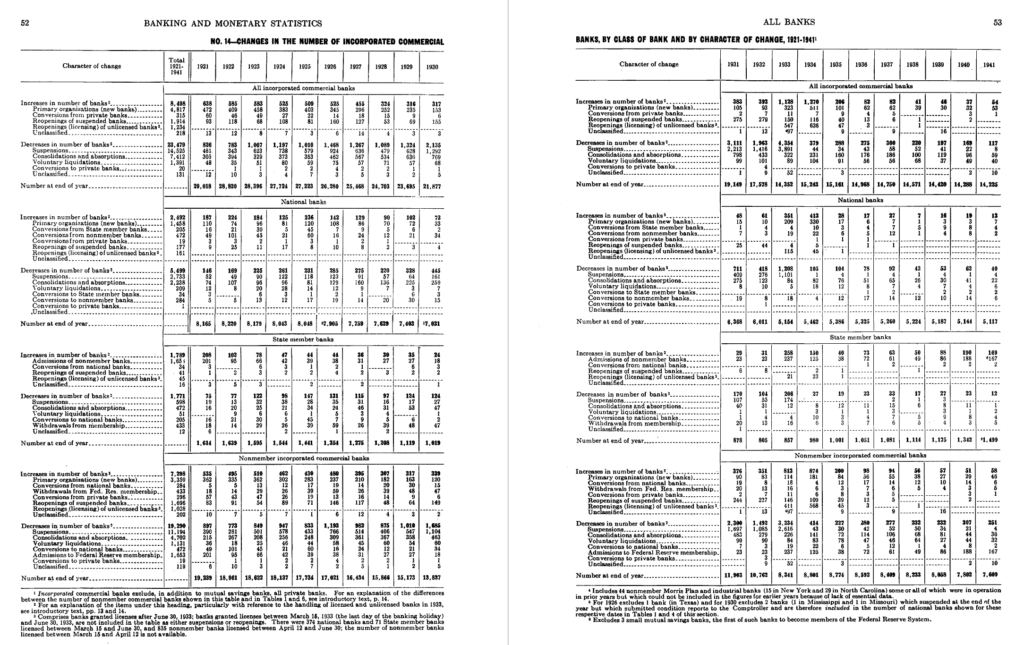

In those days, banks were classified as National Banks, all of which appear to also be members of the Federal Reserve System; State Banks that were also Fed Member Banks, and a large number of very small State Nonmember banks. There were a lot of State laws against branching etc., which led to a large number of basically one-shop banks, a single storefront.

At the end of 1928, there were 15,866 Nonmember Banks, 1,208 State Member banks, and 7,629 National Member Banks.

By the end of 1933, 2011 National Banks had closed, 380 State Member banks, and 7049 Nonmember banks. More than half of the National Bank closures were in 1933, probably related to the Bank Holiday and restructuring. A lot of banks also merged, with the weaker selling out to the stronger. At the end of 1932, there had been 910 National Bank closures, and 4433 Nonmember banks closing. In terms of closures, most of the action was in the Nonmember banks, which of course are those banks which, since they were not Fed Members, could not borrow from the Federal Reserve.

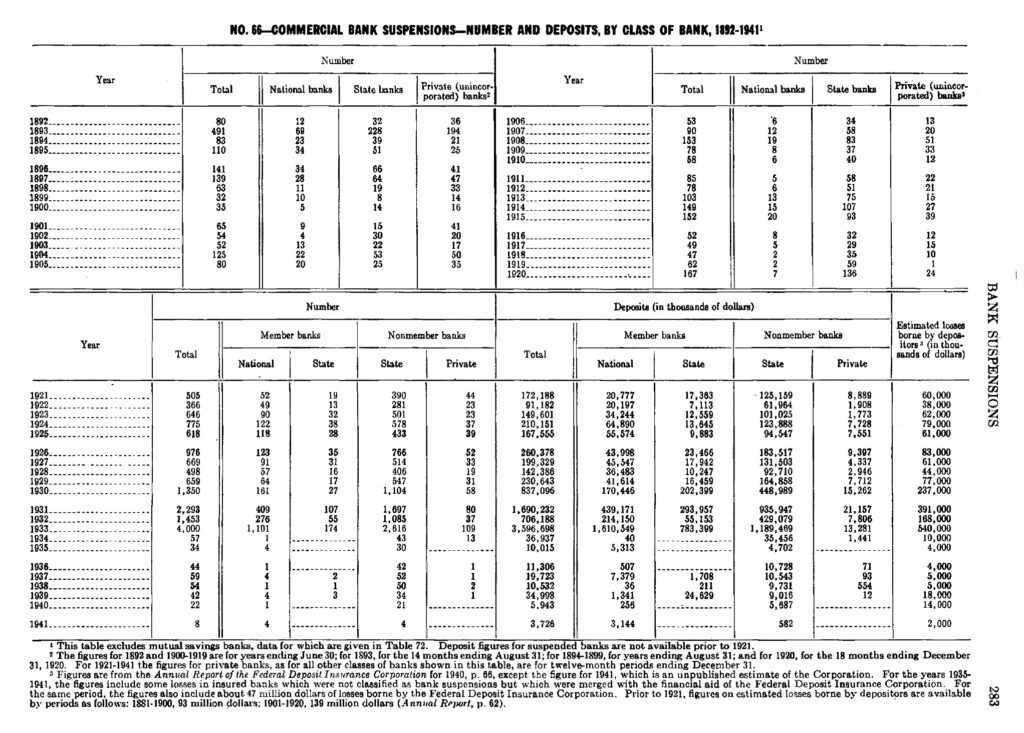

As for the dollar amounts of suspended deposits, we see that the big losses were in Nonmember banks. They were small banks, but all together there were a lot of losses. A total of $1,690 million of deposits were suspended in 1931. Of these, $439m were from National Banks. State Member banks failed all out of proportion to their small numbers, at $294 million of suspensions. Nonmember banks had a whopping $936 million of suspensions. The estimated losses to depositors were $391 million out of $1,610 million of suspensions. In other words, depositors eventually got $0.76 back on every dollar deposited. But, this took a while, as there was a legal process involved. They couldn’t spend the money during that time, which led to problems. State Member banks were particularly weak in 1930 also. In 1930, 161 National banks suspended withdrawals, and 27 State Member banks. However, the amount of suspensions was $170m among National banks, and $202m among State Member banks. This category seems particularly weak, and we can wonder why that is. Probably, they had preexisting problems which prevented them from achieving National Bank status, even before 1929.

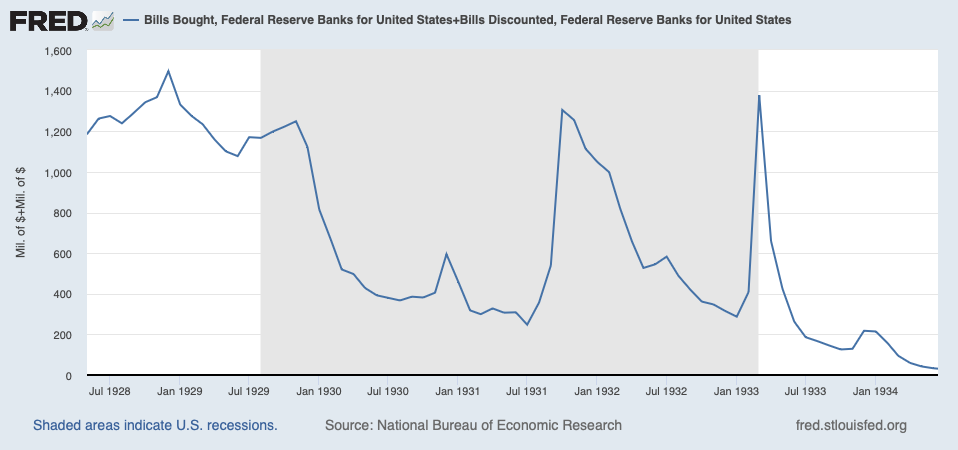

In 1929-1932, National Banks had a total of $864m of suspensions. State Member banks had another $556m. In total, that is $1,420m of suspended deposits. In those years, depositors eventually suffered losses of about 25.2%. Theoretically, the Federal Reserve could lent to these banks, covering their entire suspended deposit base of $1,420m. They had that balance sheet capacity. Then depositors would have made no losses. The bank still would have shut down, but all of its deposits would be owned by the Federal Reserve. The Fed would then eat the 25.2% loss on those deposits, or about $358m — close to total capital of $420m in 1931. Also, the Federal Reserve would get the pleasure of sitting in bankruptcy court for months or years to collect the remaining 74.8% — all things which the Federal Reserve was explicitly set up not to do, and was contrary to all principles of the time (and today, where this is done by the FDIC, not the Fed). This would have been completely against its existing policy of only lending against “eligible paper,” via Bills Bought or Bills Discounted. Certainly not the entire balance sheet of these banks consisted of “eligible paper.” Most of it was probably long-term loans, of questionable quality. Most of these banks probably did sell or borrow against all their “eligible paper,” either with the Fed or another bank. So the Fed might not have been able to do much of anything at all, according to the rules of that time. Also, we can then ask why the Fed should eat the 25.2% loss that should have been borne by depositors. Much of the problem was at State Member banks, a category that seems particularly weak, and probably seemed so at the time as well. Why should the Fed bail out the depositors in these second-tier losers, who apparently didn’t even qualify for National Bank status? Of course the Federal Reserve did expand its lending and discounting in 1931, by about $1,090 million. So what was the problem?

These are all interesting questions, which come up immediately when investigating this topic, and which can be answered very easily by looking at the available resources from the Federal Reserve itself, via FRED and FRASER online. I did it in a couple hours this morning. But, you won’t hear about any of this in this book.

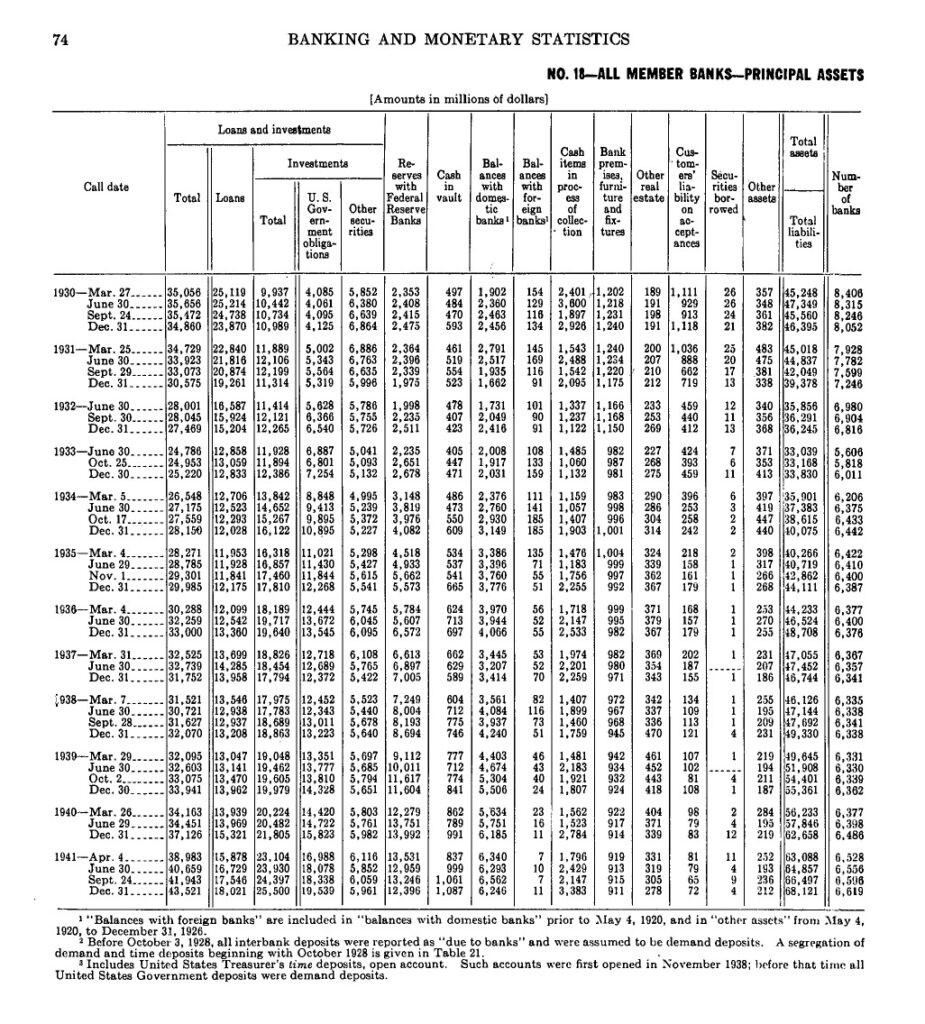

At the end of 1930, about 51% of Total Assets of Member Banks consisted of Loans. There were also 23.7% of Investments (marketable bonds), including 8.9% of Government Bonds. Of course any bank in distress can sell all of its government bonds to meet withdrawals. It can sell the Corporate bonds too, although this would have been more difficult since prices were bad.

Of these Loans, about $736m out of $23,870m of Loans were Open Market Paper, mostly the “eligible paper” against which the Fed would lend. That is only 3.0% of Loans and 1.6% of Total Assets. And, no doubt, at troubled banks suffering withdrawals, even this small sum would be sold, leaving only the long-term loans as available assets.

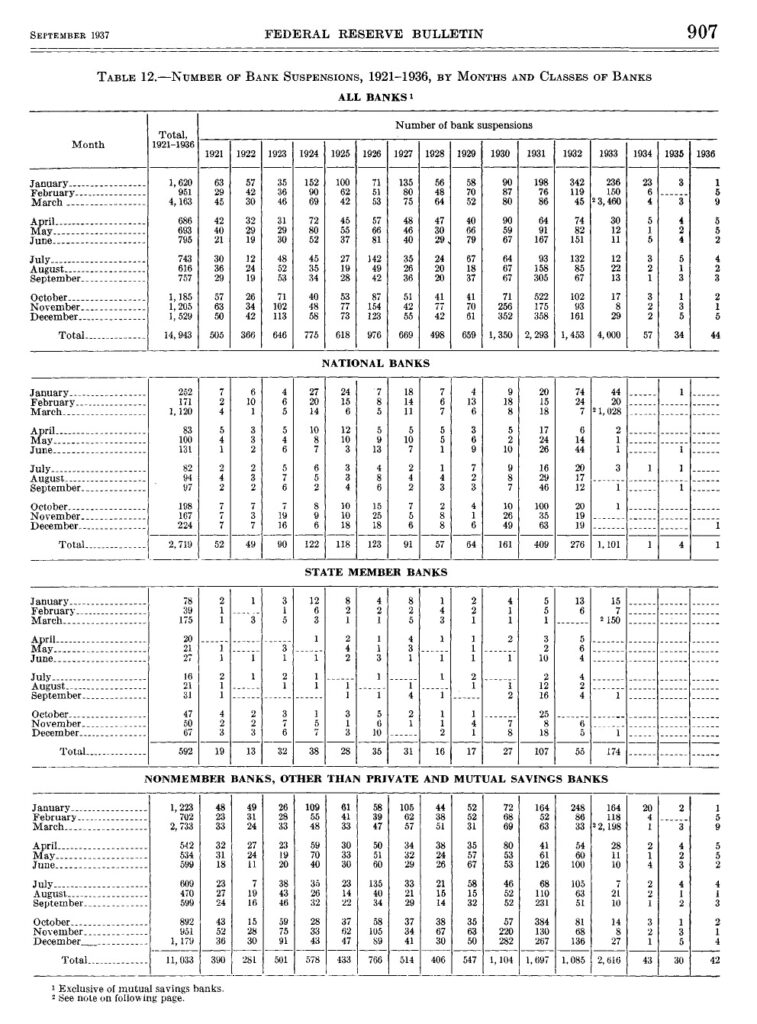

Here is a little info on the timing of bank suspensions. It is from the Federal Reserve Bulletin, September 1937.

We can see that there wasn’t really much going on until the end of 1930. This calms down again by February 1931. Then, there is a burst of failures starting in September 1931, with the British devaluation, and other devaluations worldwide. This of course meant huge losses on all foreign bonds and investments. So, until September 1931, there wasn’t all that much stress on the banking system. It wasn’t that much higher than in 1926. After September 1931, there was in fact a huge burst in lending by the Fed, which was followed by the RFC in early 1932.

In the end, the problem this book runs into is not these interesting investigations into the Federal Reserve’s capacity of, or justification of, lending to troubled banks. The problem is blowing a lot of smoke to justify what the book is really about, which is selling Quantity Theory, or Friedmanite Monetarism. This is a floating-fiat-currency system of macroeconomic manipulation, which the Fed certainly should have rejected in the 1929-1932 period, and did.

Good for them.