We’ve been talking about NGDP Targeting, which is a popular notion among somewhat right-leaning economists these days. I gave some of my overall impressions of the proposal. Then, I wanted to let some of its proponents speak for themselves, and see what we could gather from that.

September 15, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting

September 22, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #2: The Classicals and the Mercantilists

September 29, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #3: What’s The Value?

October 6, 2019: Let’s Talk About NGDP Targeting #4: A Pattern of Continuous Currency Decline

Today, I will start with a pretty good review of NGDP Targeting-related ideas down through history, from George Selgin. It is here:

Selgin: Some “Serious” Theoretical Writings that Favor NGDP Targeting

I characterized the proposal as being straight down the middle of the “Mercantilist” or “Soft Money” ideal, really not much different than the money-manipulation notions described by James Denham Steuart in the 1760s. Thus, it is no surprise that we find similar ideas expressed throughout the twentieth century, since they haven’t really changed much since the eighteenth. If this long trek through related literature is a bit much, this Twitter summary by Selgin is informative:

I think this described pretty nicely exactly what I’ve been saying: this is a variant of “Soft Money” economic manipulation (“management”) via monetary distortion. That is why you can make pretty straight connections to other such “soft money” doctrines, including Keynesian and Monetarist varieties. Nowhere here is there any interest in the value of the currency, or keeping that value stable, in this way achieving a “neutral” currency comparable to an unchanging kilogram or meter that does not introduce monetary distortion of the economy. This is the primary Classical “Hard Money” concern, and also the primary policy choice of more than half of all countries today.

“Austrians” have been one of the primary advocates of a “Hard Money” or “Classical” approach throughout the twentieth century, with its primary figure Ludwig von Mises a consistent defender of the gold standard system. Those who don’t know too much about it might be confused by the inclusion of Hayek and “Austrians” in general here, but we saw earlier that at no point in his entire career was Hayek ever a fan of the gold standard. He was mostly in favor of “price stability” or “purchasing power stability,” which for him mostly meant a commodity basket, and was unceasing in his disdain for and criticism of the primary monetary system of the world during his lifetime, the gold standard. Thus, Hayek acted as a subversive during his career, undermining the established existing order. Not surprisingly perhaps, in 1931-1950 he taught at the London School of Economics founded by the Fabian group, who were overtly committed to undermining existing institutions in slow incremental steps, with an end goal similar to the Marxists although by different means.

Hayek at least understood that anything like a CPI would vary from country to country, and thus a CPI target would result in currencies that float against each other, producing all sorts of difficulties. Commodity prices could produce an internationally-shared standard of value. But, at varying points in his career, Hayek also made some comments that seemed to be in favor of more of an NGDP Targeting approach. (Apparently, there was a brief mention on the topic by Hayek in 1933, and another in 1975.)

January 13, 2019: Good Money, Part I: The New World, by Friedrich Hayek

February 10, 2019: Good Money Part I #2: Hayek’s Early Enthusiasms

February 16, 2019: Good Money Part I #3: The Depression Years

March 3, 2019: Good Money Part I #4: Nothing To Say About The “Business Cycle” In The Middle Of The Great Depression

March 10, 2019: Good Money Part II: The Standard, by Friedrich Hayek

April 21, 2019: Good Money Part II #2: Currency Choice

April 28, 2019: Good Money Part II #3: The Future Unit of Value

Milton Friedman played a similar role as Hayek, during the 1950s through the 1980s. On most points, like Hayek, he reiterated and expanded upon important principles of liberty and free market capitalism. But, like Hayek, he differed on one point. Friedman was never a supporter of the gold standard, and excoriated it at every opportunity. This is of course common today, but Friedman was doing this during the 1950s and 1960s, when the gold standard, in the form of the Bretton Woods arrangement based around the dollar at $35/oz. of gold, was the organizing principle of the world monetary system, the official policy of the Federal Reserve, U.S. Treasury, the IMF and most world governments, just as it had been the organizing principle in past decades and centuries. Also, the Bretton Woods system, despite is many internal contradictions and tribulations, was, by all appearances, producing excellent results — the best economic results of the past century since 1914. Thus Friedman took the role of a subversive, undermining the existing order (the existing order that was working quite well), and directly contributing to its collapse in 1971. It is not so surprising that the gold standard would come under criticism during the 1930s, when people were flailing around for solutions to the very great problems of that time, but it is rather incongruous during the 1950s and 1960s, when there were no such problems. This is a repeating pattern that people should be aware of, and sensitive to.

CPI targeting and NGDP targeting are actually not much different. Going back even to Irving Fischer in the late nineteenth century, “price stability” or “purchasing power stability” approaches have tended to be somewhat surreptitious means of introducing an element of “Soft Money” macroeconomic manipulation while seeming to adhere to Classical ideals of a “neutral currency of stable value.” (This was important at the time, when the Classical view of money was still dominant.) Obviously, if CPI Targeting and the gold standard produced the same results, there would not be much purpose for CPI Targeting.

The “purpose” or rationale for CPI Targeting comes when the CPI is falling (with a gold standard system, or in the context of a currency of stable value). These people then argue that “we must preserve unchanging purchasing power,” which amounts to an excuse for a devaluation — and exactly these arguments were a primary justification for the devaluation of 1933. In Keynesian terms, a “decline in aggregate demand” (recession) leads to lower prices, within the context of a stable currency. So we see that CPI Targeting, though strenuously claiming “neutrality,” in fact amounts to devaluation during recession. You might also have a situation where a CPI target might indicate a major currency rise, compared to what you might get with a gold standard system. Indeed, commodity prices, and prices in general, rose a lot during both World War I and World War II, due to wartime demand. Did the CPI Targeting/”stable purchasing power” people then jump up and down for a big increase in currency value, for example going from $20.67/oz. to $15/oz. in World War I, or from $35/oz. back to $20.67/oz during World War II? They did not — and not surprisingly, since this would have been destructive and recessionary. Thus, in practice (although strenuously denied in theory) these “stable purchasing power” arguments, leading to today’s CPI targeting, tend to serve as a one-way-street justification for devaluation — although, not too much devaluation — and indeed this is exactly the purpose that it seems to have served in the 2001-2012 period, with the CPI itself jimmied to produce the desired results.

Nevertheless, CPI targeting has been embraced in recent years because it helps escape the problem of the “dual mandate” that the Federal Reserve has been charged with. It has been a step toward a more Classical ideal of a currency that is not manipulated by central banks to achieve certain economic outcomes (they hope), but rather one that remains “neutral.” It also reflects the recognition of the need for a currency standard that can serve multitudes of countries, such as the 40 countries that are part of the “dollar bloc” and 44 countries part of the “euro bloc” (according to the IMF). If the German economy is doing well, and the Greek economy is doing badly, what are you going to do if you have an overt mandate to “manage the macroeconomy”? Thus, it makes sense that the ECB would embrace a “single mandate” approach that doesn’t force them to commit to direct macroeconomic management. In practice, as we discussed last week, foreign exchange rates (basically, a sort of Stable Value) have taken priority over CPI targets, and the eurozone CPI has been allowed to print low figures, so that the euro wouldn’t have to be devalued more than it has already been.

Today, we will look at another argument for NGDP Targeting, this time from Scott Sumner, also of the right-leaning Mercatus Center at George Mason University, in this case the Director of the Program on Monetary Policy. He is also a Research Fellow with the right-leaning Independent Institute, and teaches at Bentley University. We looked at Sumner’s book on the Great Depression earlier, and mostly didn’t have very nice things to say about it:

July 23, 2017: The Midas Paradox (2015), by Scott Sumner

July 31, 2017: The Midas Paradox #2: Blame Gold

August 3, 2017: The Midas Paradox #3: It’s So Because I Say It Is

August 11, 2017: The Midas Paradox #4: Much Ado About Nothing

August 18, 2017: The Midas Paradox #5: It’s Getting Uncomfortable in the Prices, Interest Money Box

Here is Sumner’s 2012 paper on NGDP Targeting:

read: “The Case for Nominal GDP Targeting,” by Scott Sumner

As before, I can’t really go line-by-line through the 24-page paper, but I will try to summarize the main points and also give my responses to those main points.

THE GOLD STANDARD

It is not hard to see why gold and silver were used as money for much of human history. They are scarce, easy to make into coins, and hold their value over time. Even today one finds many advocates of returning to the gold standard, especially among libertarians. At the same time most academic economists, both Keynesian and monetarist, have insisted we can do better by reforming existing fiat standards.

It is easy to understand this debate if we start with the identity that the (real) value of money is the inverse of the price level. Of course, in nominal terms a dollar is always worth a dollar. But in real terms, the value or purchasing power of a dollar falls in half each time the cost of living doubles. During the period since the United States left the gold standard in 1933, the price level has gone up nearly 18 fold; a dollar in 2012 has less purchasing power than 6 cents in 1933. That sort of currency depreciation is almost impossible under a gold standard regime. Indeed, the cost of living in 1933 was not much different from what it was in the late 1700s. This is the most powerful argument in favor of the gold standard.

The argument against gold is also based on changes in the value of money, albeit short-term changes. Since the price level is inversely related to the value of money, changes in the supply or demand for gold caused the price level to fluctuate in the short run when gold was used as money. Although the long-run trend in prices under a gold standard is roughly flat, the historical gold standard was marred by periods of inflation and deflation.

(p. 5)

Sumner’s opinion of the gold standard is perhaps not so relevant, but it is distressing that he makes such rudimentary errors right out of the gate. The purpose of a gold standard is stable value, which has never been “stable prices.” Prices are assumed to go up and down, for various reasons having to do with the supply and demand for goods and services; or what Mises called “goods-induced” as opposed to “money-induced” changes in prices. David Ricardo made the same distinction, as I have also many, many times. This is either rank incompetence or, more likely, intentional misrepresentation.

February 19, 2017: “Prices” and Value

July 20, 2018: This is Why We Want 5% “Inflation”

July 26, 2019: Stable Value is our monetary goal, not “Stable Prices”

The Keynesians have the idea of “aggregate supply” and “aggregate demand,” which make “aggregate prices” (basically, something like the CPI) go up and down, in the context of a currency of stable value. So, it is not just the Austrians.

I won’t get into Sumner’s description in too much detail, since it includes a lot of things that we have already discussed. He does make the typical poses that we find among NGDP Targeting fans, who are mostly on the political Right: they like to give airs that they are on the Classical or Hard Money side of the aisle, when they are really Soft Money currency manipulators to the core. (This is also why Hayek is enthusiastically cited.)

A different monetary policy system could enhance predictability and ensure sound money.

This primer will present one such system: nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) level targeting.

(p. 3)

“Sound Money” has always only meant one thing: a gold standard system. In principle, it means a currency that is unchanging in value and free of manipulation — like the 700+ years that the Byzantine solidus maintained the same quantity of contained gold. You would have to be a little dumb to fall for this, but unfortunately a lot of generalists (Congresspeople for example) who don’t know too much about these things are easily fooled.

I am struck by the impression that the recent popularity of NGDP Targeting is related to the 2008 financial crisis.

Recall that inflation targeting is about more than just inflation. Advocates like Bernanke see it as a tool for stabilizing aggregate demand and, hence, reducing the severity of the business cycle. This is understandable, as demand shocks tend to cause fluctuations in both inflation and output. So a policy that avoids them should also stabilize output.

I have already discussed one problem with this view: The economy might get hit by supply shocks, as when oil prices soared during the 2008 recession. Some of that can be avoided by looking at the core inflation rate. Standard macroeconomic models predict that a reduction in aggregate demand will cause wage growth to slow, leading to lower core inflation. But even the core inflation rate was surprisingly sticky during 2008–2009, even after oil prices plunged. This made it harder for the Fed to aggressively stimulate the economy.

The problem seems to be that, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, housing prices did not fall. On the contrary, their data shows housing prices actually rising between mid-2008 and mid-2009, despite one of the greatest housing market crashes in history. And prices did not rise only in nominal terms; they rose in relative terms as well, that is, faster than the overall core CPI. If we take the longer view, the Bureau of Labor Statistics finds that house prices have risen about 8 percent over the past six years, whereas the famous Case-Shiller house price index shows them falling by nearly 35 percent. That is a serious discrepancy, especially given that housing is 39 percent of core CPI.

(p. 15-16)

This section is nice, because it begins with what I was saying earlier: that CPI Targeting, despite all its claims of “neutrality,” is, in effect a form of macroeconomic management, aimed at “stabilizing aggregate demand.” NGDP Targeting has a lot in common, just with somewhat more emphasis on “stabilizing aggregate demand,” in fact making this the explicit target, since NGDP is, basically, “aggregate demand.” Actually, it is more like “aggregate nominal demand,” which differs from Keynesian “aggregate demand” largely because the Keynesian construction assumes a currency of stable value. I think there is an essential error here mistaking Keynesian “aggregate demand” or, basically what we would call “real growth” today, with “aggregate nominal demand,” or what we would call “nominal growth.”

Now we get to the 2008 crisis, where CPI targeting, Sumner argues, would not have produced an adequate response by the Federal Reserve. NGDP Targeting would have produced a more aggressive response, and in this case would be superior — all of which I agree with.

But, let’s look at what was really happening in 2008.

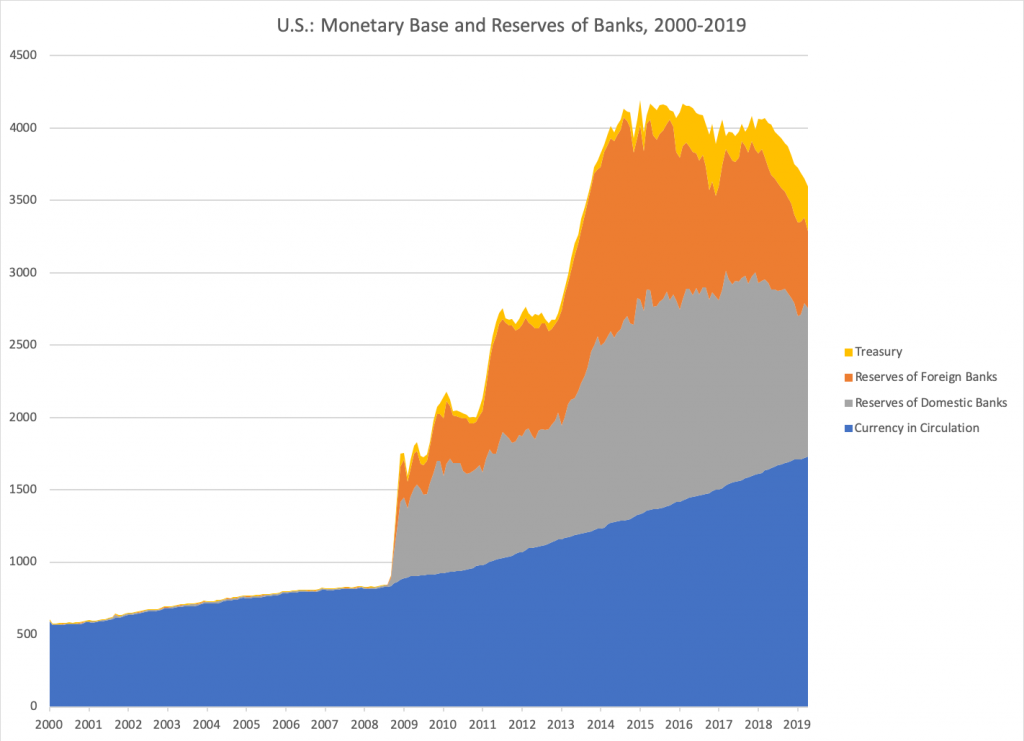

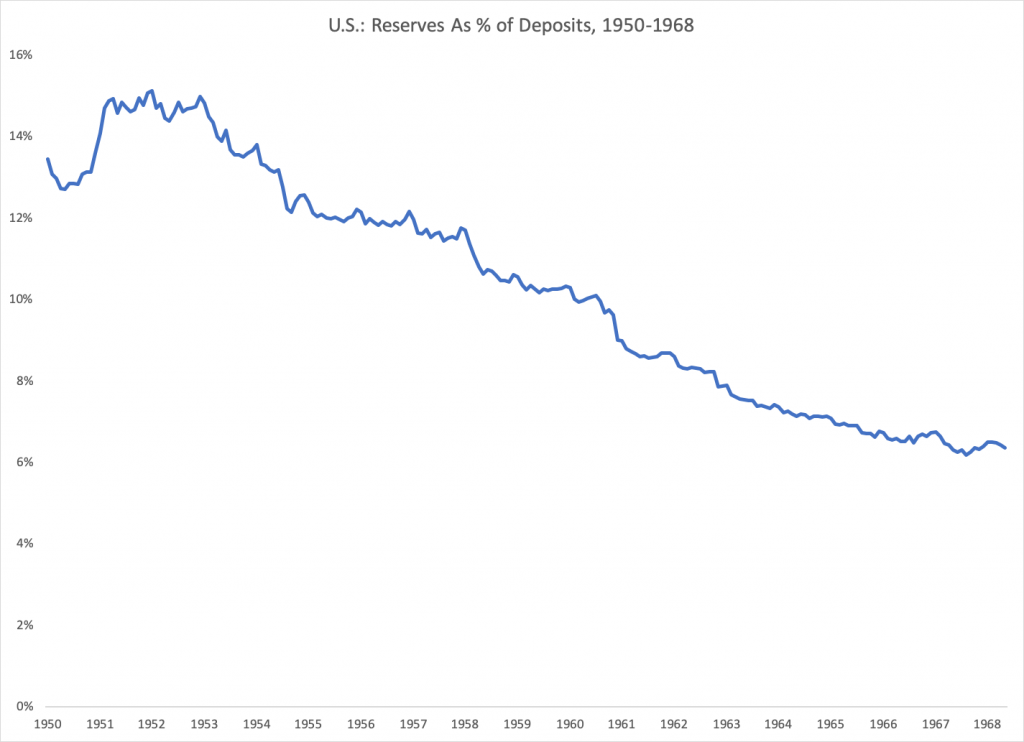

August 30, 2012: Would a Gold Standard system have worsened the 2008 crisis?

Basically, banks were working with very, very low bank reserves (that is, “cash” in the form of a deposit at the Federal Reserve, a component of base money), as a way to maximize profitability. In the midst of the 2008 crisis, banks decided that: a) they needed much more reserves to meet commitments; and b) they didn’t want to lend to other banks, since they might not get paid back. The result of this was an explosion of demand for bank reserves, which was eventually met with discount lending, and then a variety of measures including “QE.” This actually brought banks back to their conservative 1950s-era operating norms. We have recently learned that this has apparently been codified in the form of Basel III regulations; so that large banks are, in effect, now required to hold large, 1950s-style reserves. We looked into this in depth:

May 26, 2019: The Federal Reserve and Bank Reserves

June 2, 2019: The Federal Reserve and Bank Reserves #2: What’s Old Is New Again

June 9, 2019: The Federal Reserve and Bank Reserves #3: Mission Accomplished

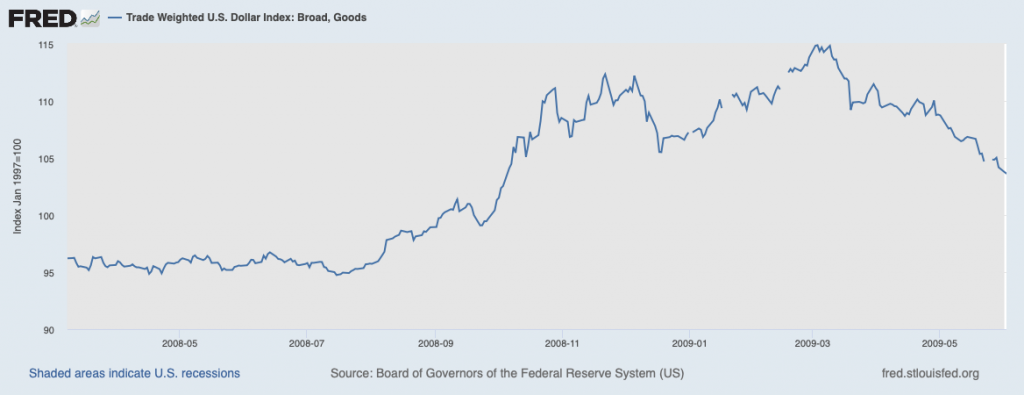

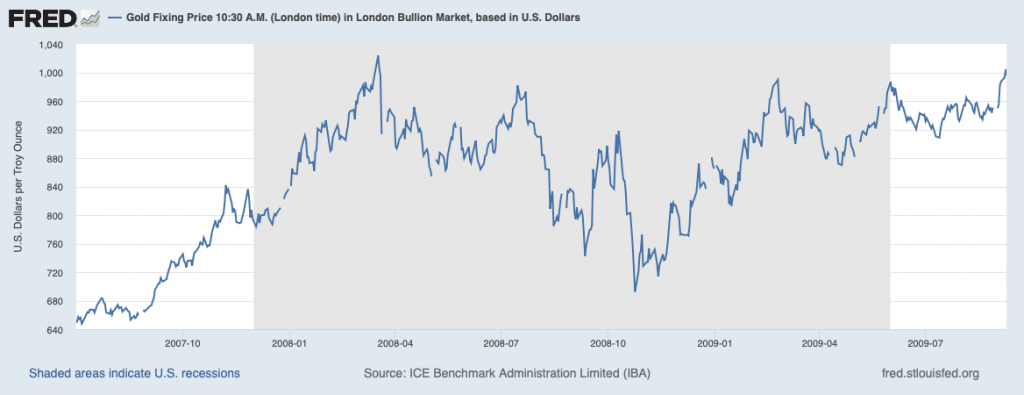

This new demand for dollars ended up producing a sudden surge in the dollar on foreign exchange markets, and compared to gold:

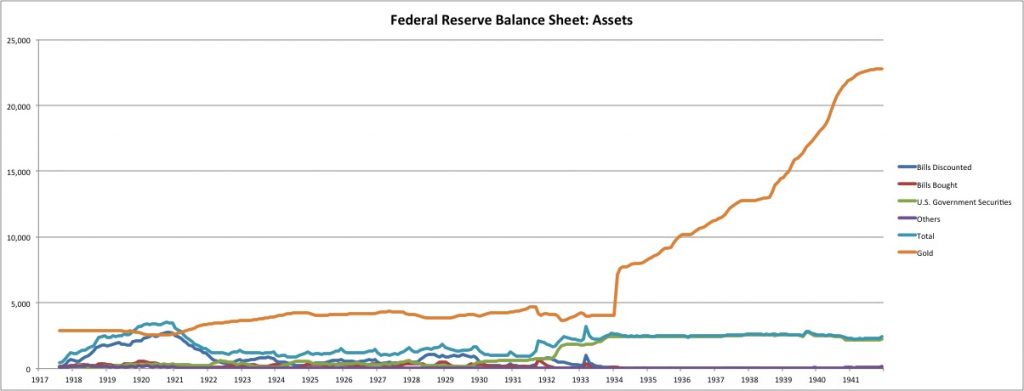

I argued that a gold standard system, for example at $1000/oz., would have automatically increased the base money supply to keep the dollar from rising, in the process producing the same sort of monetary expansion to meet rising demand for bank reserves, just more quickly and more smoothly, and also avoiding all the turmoil of these huge forex moves and all their macroeconomic consequences. This is very similar to what happened, at a slower pace, during the late 1930s, as the monetary base grew enormously to meet growing demand for bank reserves at banks.

June 18, 2017: The “Gold Sterilization” of 1937

June 25, 2017: The “Gold Sterilization” of 1937 #2: Fumbling and Bumbling

July 9, 2017: The “Gold Sterilization” of 1937 #3: The View From 2011

The NGDP Targeting people have a point, which is that there really was a monetary problem during that time to be corrected, and a CPI Targeting system may not have done that well (and didn’t). But, it would have been corrected more effectively with something like a gold standard system.

Even if (arguably) a gold standard system would not have effectively dealt with the problem via its automatic mechanisms (basically, to increase the monetary base whenever the currency tended to rise beyond its gold parity), there could have been some kind of intentional discount lending to banks that was also compatible with the gold standard system — this is the nineteenth-century “lender of last resort” principle as practiced by the Bank of England. We saw earlier from David Beckworth that, at least as we interpret Beckworth’s view, the use of an NGDP Target in 2001-2017 probably would have led to a lot more dollar depreciation even than there was during that time, which was: a lot!

Or, to summarize: NGDP Targeting wouldn’t have really dealt with the problems of that time very well, although I can agree that it would have been better than CPI Targeting.

Sumner then wraps things up, and I don’t think there is too much left to comment on. Thus we come to the end of this paper too, and again we find nothing at all about the value of the currency, or the effects of this policy upon currency value (which I consider its primary operating mechanism and raison d’etre), or anything about any other aspect of economic policy (including all nonmonetary elements), or the international consequences of such a policy, especially when there are about 40 countries worldwide that are now part of the “dollar bloc,” or the foreign exchange rate consequences, or any of the many other things that, as I said in summary earlier, tend to get completely ignored by the NGDP Targeting people, who live in their little bubble of simple simplistic simplicity.

March 24, 2016: The Simple Simplistic Simplicity of ‘Nominal GDP Targeting’

So we can see that I am not just making this up, or even exaggerating.

I hope the general reader can get at least an idea of the current state of discussion regarding “rules-based” approaches to monetary policy, which is not very good if you ask me. In the meantime, more than a hundred countries worldwide use a very simple “rules-based” principle: they tie their currency to an external standard of value, typically either the dollar or euro. A gold standard system is the same basic idea, and has proven itself over multiple centuries of use, which included the entirety of the Industrial Revolution up through 1971. The world got rich with the gold standard; today, although technology continues to progress, we have to live with what one Soft-Money advocate on the Left called: “The Age of Diminished Expectations,” and what one on the Right called: “the Great Stagnation.”