A friend asked me to comment on Leland Yeager’s introduction to The Gold Standard: An Austrian Perspective, from 1983. It turns out that I actually made a few comments on this book already, which are here:

May 20, 2019: The Gold Standard: An Austrian Perspective

I generally thought the contributions to the book were pretty good, and that they avoided many of the errors common at that time.

Leland Yeager was one of the better economists of that time, so his introduction will serve as a nice short, digestible summary of relevant topics.

A gold standard is simply a policy of maintaining the value of a currency equivalent to a certain amount of gold. It is a fixed-value system. This could be accomplished, for example, with the use of debt instruments. A common money-market fund is “equivalent to dollars” for most people, with daily liquidity (conversion into actual dollars). But, an MMF holds no “dollars.” It does not hold any banknotes, or bank reserves, the only two components of dollar base money today. It has no “dollars in reserve.” If you withdraw from an MMF, the MMF does deliver real “dollars” however. In practice, these are bank reserves at the Federal Reserve, a component of base money. This is done through the commercial banking system.

In practice, we may wish a gold-standard currency-issuing body, whether a central bank or a private currency-issuing institution, to hold actual bullion as an asset, or a “reserve.” We may also wish for this institution to be legally obligated to deliver bullion in exchange for currency liabilities, or “gold conversion,” just as an MMF today must deliver “dollars” in exchange for its liabilities (or actually equity). The amount of reserves such an institution can have might be high or low, from 2% to 100% or more.

There are no societal “resource costs” of this gold reserve, which I have argued in the past.

June 30, 2016: The Nonexistent “Social Costs” of a Gold Standard System

Gold mining has continued, unchanged, since the end of the worldwide gold standard system in 1971. More than half of all the gold ever mined in human history, has been mined since 1971. Having/not having a gold standard monetary system will produce no meaningful change in gold mining in the future, just as it has not in the past.

What about for currency issuers, like central banks? Gold reserves, for them, do not have a “cost.” They traded costless paper for gold, so they got the gold reserves basically for free. Rather, holding gold reserves reduces profitability. If they held income-producing debt instead, they would make more money. Gold bullion does not produce this income, so profits to currency issuers are lower.

From the standpoint of a currency user, the costs are the same. You have to work an hour for $20. Whether this $20 is “backed” by X amount of gold in a vault or not, makes no difference to you.

Maintaining a high-quality gold coinage might have some “costs” to the coinage issuer (government mint) due to coin wear, and the necessity of replacing and reminting old, worn coins.

Here we have the complaints about a “pseudo gold standard” from the Austrian camp, aimed at the Supply-Siders’ “gold price rule.” This is typical bad argument by “definition.” Basically, a “gold standard system” is “defined” as whatever specific institutional arrangements are preferred by the author. If the author insists on a 100%-reserve system, then a gold standard is “defined” as a 100% reserve system. If the author insists on a variable-reserve system, but with convertibility of banknotes into gold coinage by the issuer, then a gold standard system is “defined” as that. Anything that doesn’t fit the author’s personal, idiosyncratic “definition” is “not really a gold standard.” It is all a load of horseshit that, to be honest, gets rather old.

May 17, 2019: Defining Away the Gold Standard

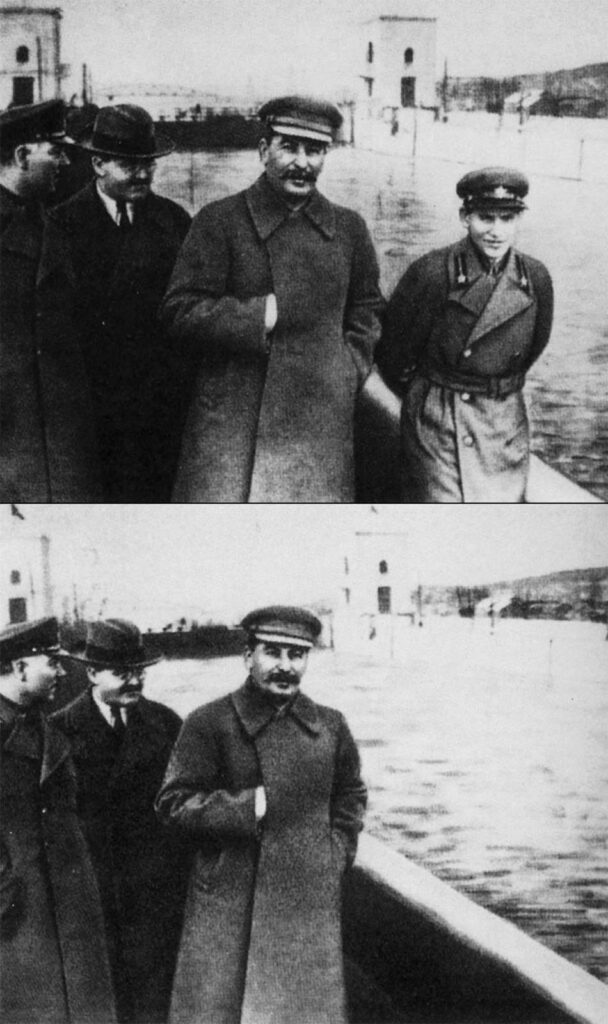

I think this “definitional argument” has been used by Team Fiat Money (including NGDP Targeting fans as you find at places like the Cato Institute) to “define away” the gold standard, for example in the 19th century. Basically, it is a psyop — an intentional “rewriting of history” to airbrush out the gold standard like a photograph from the Soviet era.

Now, I think that there are legitimate criticisms to a system (“gold price rule”) where there is little in the way of institutional guarantees (such as bullion convertibility) to prevent currency managers (central bankers) from playing silly games. But, any system that maintains the value of a currency at a specific gold parity, or in other words a “gold price rule,” is a gold standard system. That is why I wrote my second book, Gold: The Monetary Polaris, to encompass a variety of operating mechanisms, instead of the typical “I have thought about it a lot and so you have to do things exactly as I say” approach of most writers. The fact of the matter is, there have been a lot of different “gold standard systems” over time. During the late 19th century, there were centralized Central Bank systems (Bank of England), systems based solely on convertibility into international gold standard currencies (basically, a strict British pound currency board) as used in India and Japan, “free banking” systems (US before 1860, maybe Canada in the 1880s), hybrid “free banking” systems (US after 1879), systems which used both domestic bullion convertibility and foreign exchange (Sweden), and many others. They all worked.

Edwin Walter Kemmerer is a little different than all these blowhards, because he actually set up functioning gold standard systems in a number of countries between 1900 and 1930, including: The Philippines, Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, South Africa, Germany, Chile, Poland, Ecuador, Bolivia, China and Peru.

Kemmerer agreed with me — that any functioning system that maintains the value of a currency at a certain gold parity is a “gold standard system,” whether this does/does not include bullion convertibility, X% reserve ratios, gold coinage, or whatever.

I think there is probably a long-running psyop to strew dissension between gold standard advocates by focusing on these minor differences in opinion or approach. Beware.

Nevertheless, I agree with Ron Paul that reintroducing gold bullion coins usable in exchange as legal tender would be a nice thing to have, even if 99%+ of transactions would still be with banknotes and electronic banking transfers.

The focus on “automatic balance of payments adjustments,” which I assume is the “price-specie flow” notion, is stupid nonsense (Kemmerer thought so too). So, I hope that part of the point of this paper is to say that.

March 19, 2016: The “Price-Specie Flow Mechanism”

July 18, 2016: The “Price-Specie Flow Mechanism” #2: Let’s Kill It For Good

A gold standard is a subset of a broader class of Fixed Value systems. Today, most countries in the world fix the value of their currencies (sometimes not very successfully) to the USD or EUR. The better ones use a currency board, such as Bulgaria’s EUR-based currency board. Is there a “price-euro flow mechanism” in Bulgaria? Nobody even suggests anything so stupid. It’s the same for gold. A “gold standard system” is much like a “euro-standard system,” except for the choice of the “standard of value.”

Good points here. This section comes across as a sort of generalized grumbling about the political difficulty of making meaningful changes. The way to achieve political success is to develop consensus, from clear exposition of ideas.

Here we have a longstanding problem with the “Austrian School,” which has confounded the principles of the value of a currency, and its real-world “purchasing power,” in practical terms expressed as some statistic like the CPI. These are very different, as Mises himself was aware. Unfortunately, Mises’ insights have not been transferred very much to his fans and followers. From this, it is easy to conclude that an ideal currency would be “stable in purchasing power.” While a currency of idealized Stable Value would mean (by definition) that real-world prices are not affected by changes in the Value of a currency, nevertheless, prices (or “purchasing power” or a real-world CPI) might change a lot. We make this point in our new book Inflation.

Throughout Austrian writings, there is a confusion between “conceptual purchasing power,” or what Mises calls “objective exchange value,” and which I call “the value of a currency,” and its real-life “purchasing power,” expressed by something like a CPI. If you take a dollar today, its “purchasing power” in Manhattan is many multiples lower than its “purchasing power” in dollarized El Salvador. But, the value is the same.

Yeager lapses into a certain amount of Monetarism here, another typical failure of economists. Austrians and others have a poor sense of how the Value of a currency (linked to gold) and its Supply (matching Demand at the gold parity) interact. They treat them as somehow unrelated, or only vaguely related.

Let’s take the simplest example of a country that used only gold coins. There are no paper banknotes. This was common before 1800, or 1700 if you want to be particular. Obviously, the value of the coins (assuming free minting and free use of foreign coins, which was the norm in Europe) is equivalent to their gold content. The Supply of coinage, within a certain country, is equivalent to people’s desire to hold coins. If a person wanted more coins, they would act to acquire them, for example by limiting spending (“saving”). If a person wanted goods and services more than coins in a box, they would spend the coins. In the end, the Supply of coinage would exactly coincide with the collective desire (“demand”) to hold coins. The value would, of course, be stable vs. gold.

We could make an analogy to meter-sticks. The length of a meter is unchanged. Meter-sticks of standardized length are used to build houses, and for other uses. The number of meter sticks might increase or decrease, according to the need for meter sticks, for various uses. This would, we can imagine, vary crudely in line with “economic growth,” although the relationship is only crude. Thus, we know that there is a relationship between the number of meter-sticks, and economic growth. If we just looked at the number of meter-sticks, it would seem to be intrinsically related to economic growth. This is what you could call a “Monetarist” view, with Yeager here reflecting the errors of Friedrich Hayek in the 1930s. There is no place in a Monetarist view, for a value of a currency, separate from its “purchasing power.” They seem intrinsically mixed. Every change in the “supply of money” seems to have direct effects on an economy; and since such changes are necessary, it would seem that the idea of a “neutral currency” is elusive.

From a correct Classical view, the length of the meter is unchanged, and thus serves a useful purpose as a Stable Measure of Length, much like an ideal currency, whose value doesn’t change, serves a useful purpose as a Stable Measure of Value. The number of meter-sticks goes up and down, according to people’s desire to hold, or not hold, meter-sticks of unchanging length, for their various purposes. We can see that, as long as the length of the meter is unchanged, the number of meter sticks is irrelevant, as long as there are enough of them for our daily purposes. This is the “distinction between changes in prices coming from the side of goods and services, and from the side of money.” Yeager somehow gets confused here, which just goes to show the state of things in 1983.

I agree with Yeager’s conclusion that we do need some people who actually know how to play this game. Unfortunately, this is very rare, which is why I had to write three books about it. It would be nice if some people could figure this out. As they do, the laggards will come to be seen as irrelevant.